RISE OF THE VETERAN MOVEMENT

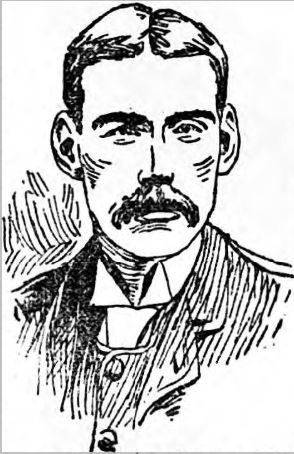

Walter Ross

In 2020, the SVHC celebrates 50 years of lively existence. Long may Masters Athletics continue to flourish!

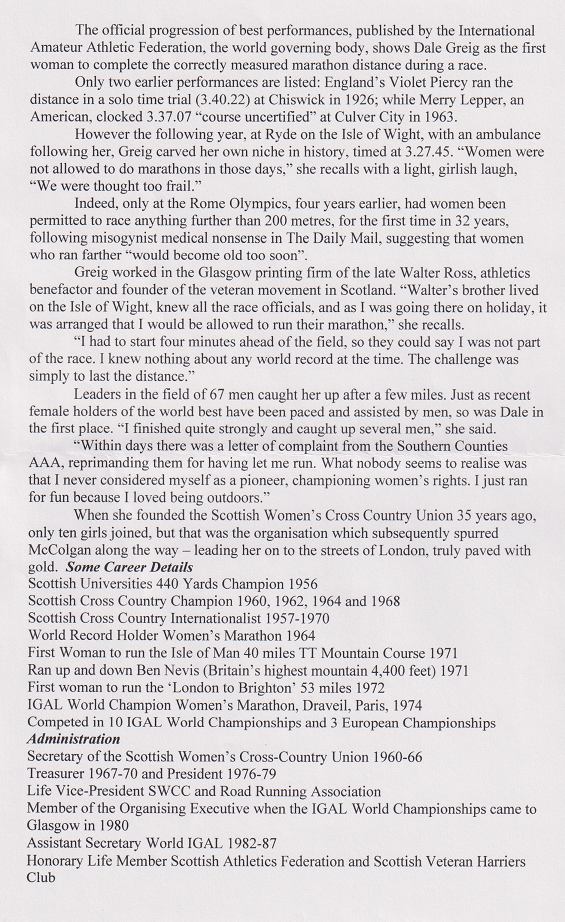

In the 1970s, the Club was almost completely organised by and for Men over the age of 40. Nevertheless, Dale Greig (a Scottish cross-country champion who, in 1967, had set the first Women’s world marathon record) did a tremendous amount of work helping the founder, Walter Ross, not only by typing up the first decade’s Newsletters, which were either a single sheet of paper, printed on both sides, or a couple of sheets stapled together. This Newsletter was posted out to members three or four times a year. DALE HAS SINCE BEEN INDUCTED INTO THE SCOTTISH ATHLETICS HALL OF FAME.

By the mid-1970s, Dale Greig and her friend [former Scottish track and cross-country champion Aileen Lusk (nee Drummond)] took part in at least two Scottish Veteran Women’s XC championships and raced as guests in Club events. However, these championships may not have been restarted until 1984, when the SWCCU accepted a W35 category in the Women’s Senior National XC.

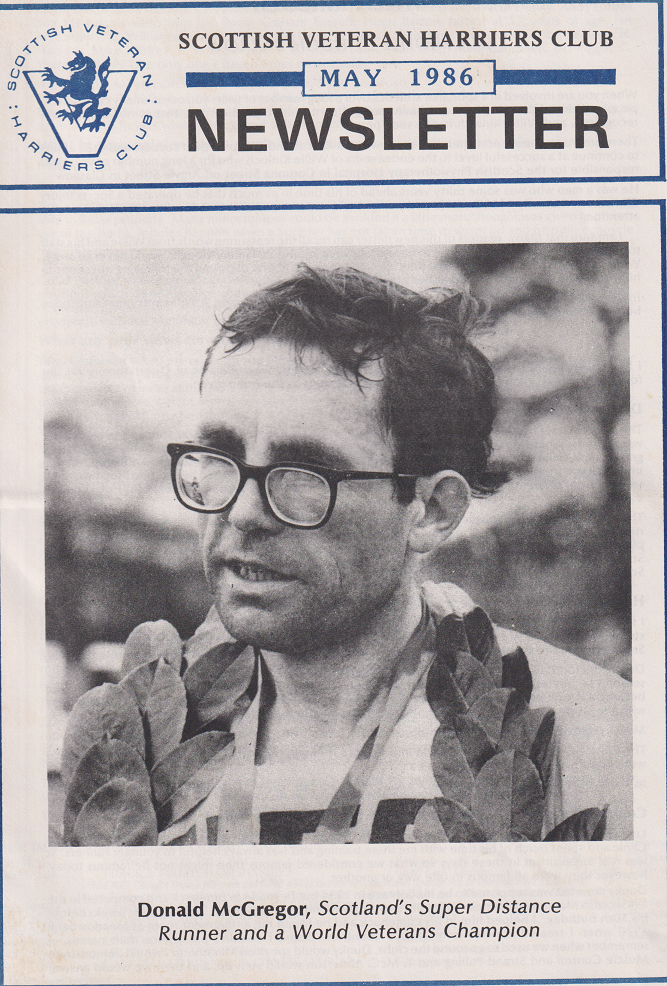

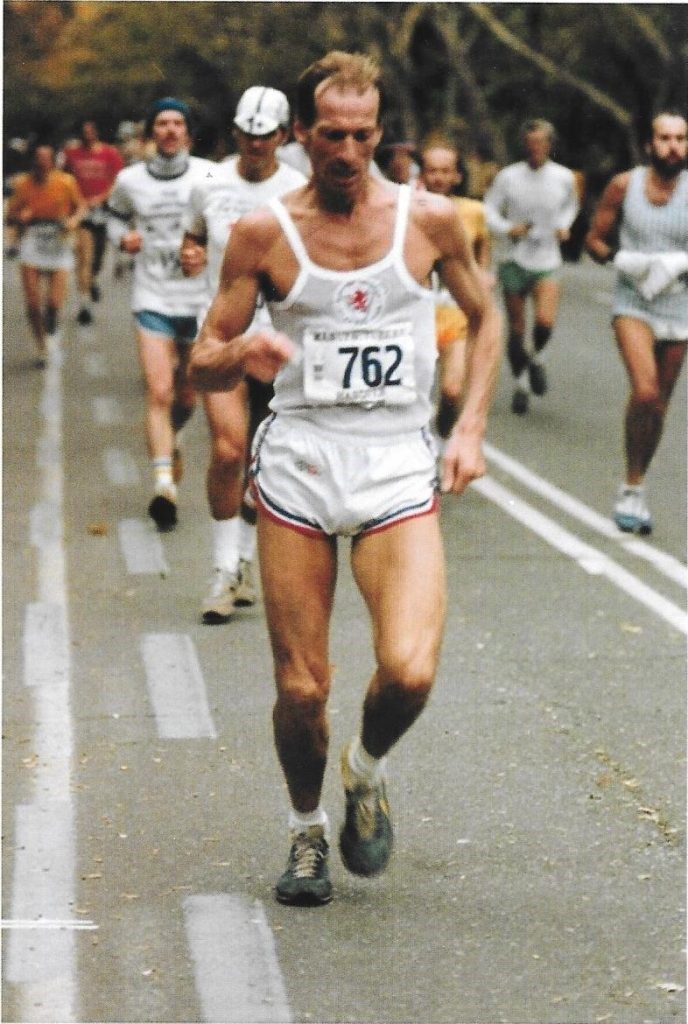

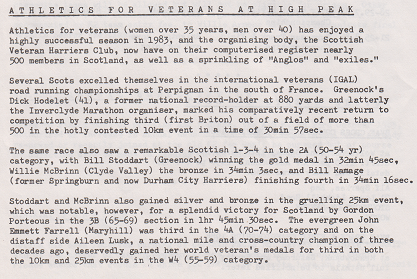

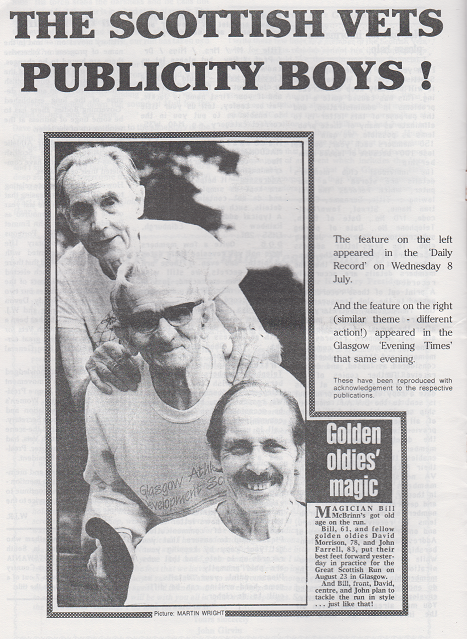

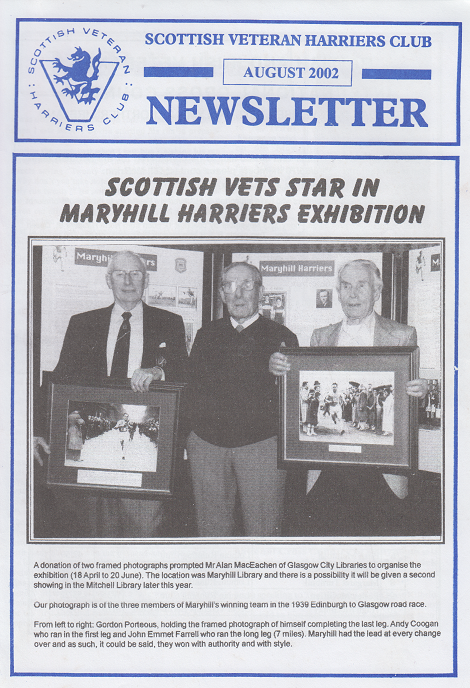

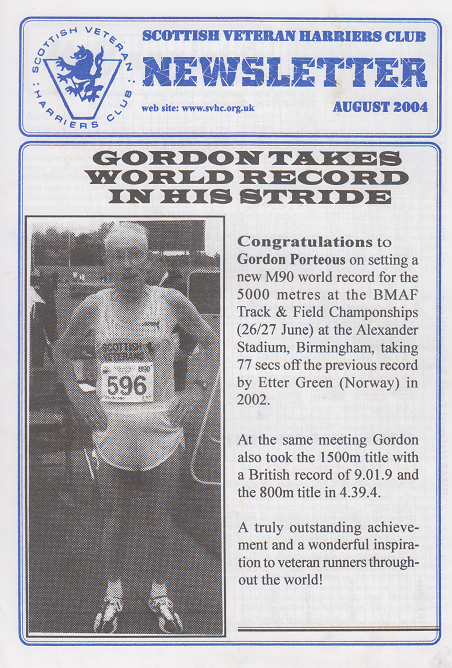

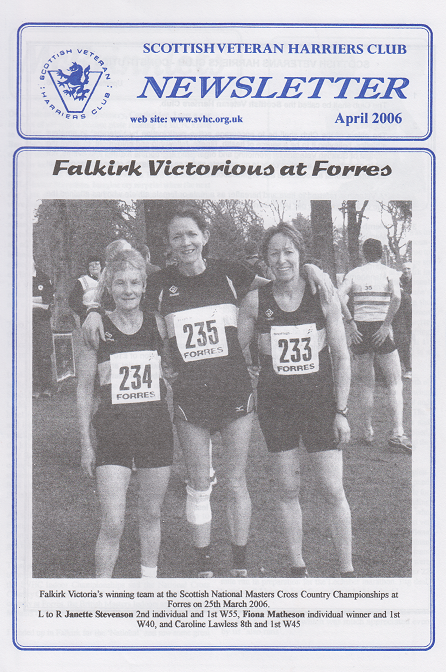

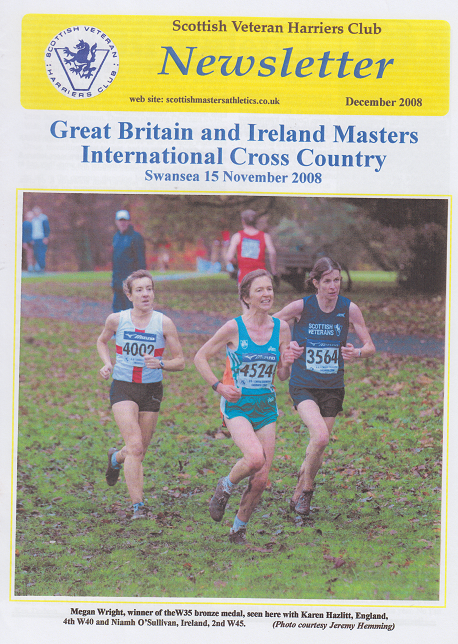

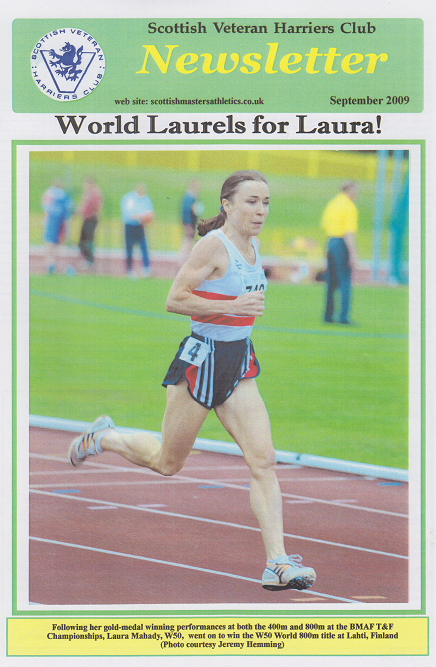

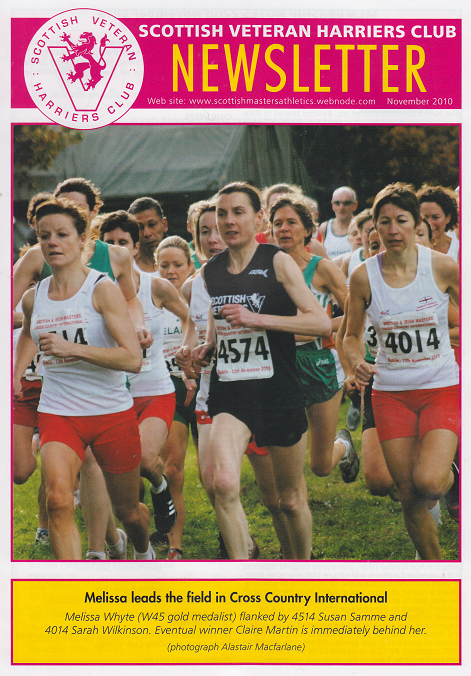

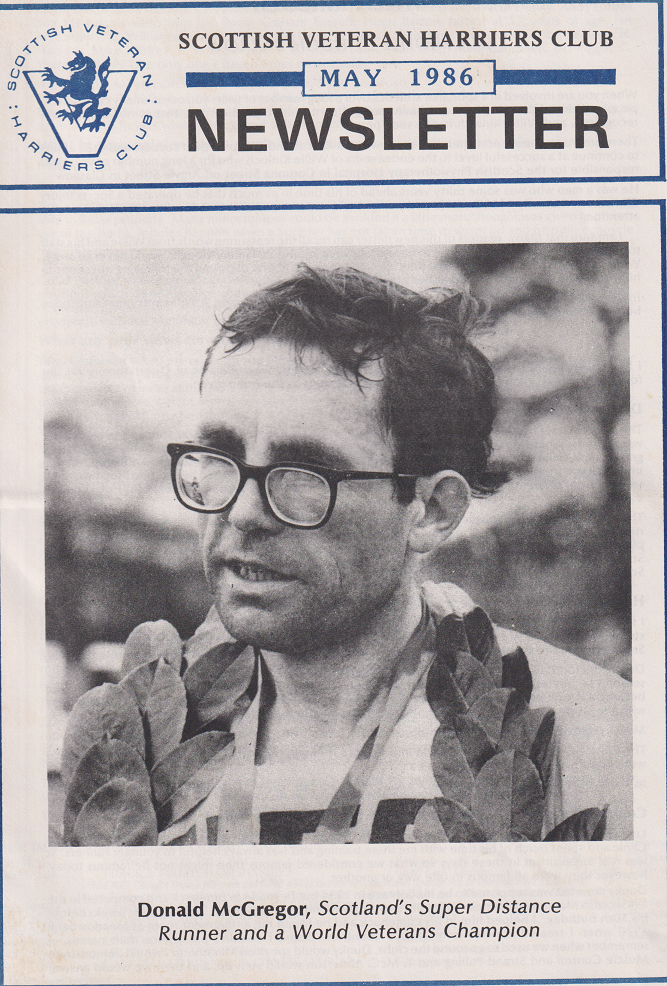

Between 1980 and 1985, competing in W50 and W55 age groups, Aileen won four bronze medals for road running in World Veteran Championships. Alastair Wood, Bill Stoddart and Donald Macgregor had been World Veteran Champions, as well as Emmet Farrell, Gordon Porteous and David Morrison. A key moment had been in late 1982, when the SVHC accepted Veteran Women as full members; and shortly afterwards, Aileen Lusk and Molly Wilmoth joined the Club committee. From then on, the number of Female SVHC runners grew steadily. From 1993, the Scottish Veteran XC Championships included races on the same day at the same venue for both sexes. Nowadays, of course, there are almost as many Female runners as Men in most events. When it comes to International Masters Championships, it seems that Scottish Women usually gain more medals than the Men.

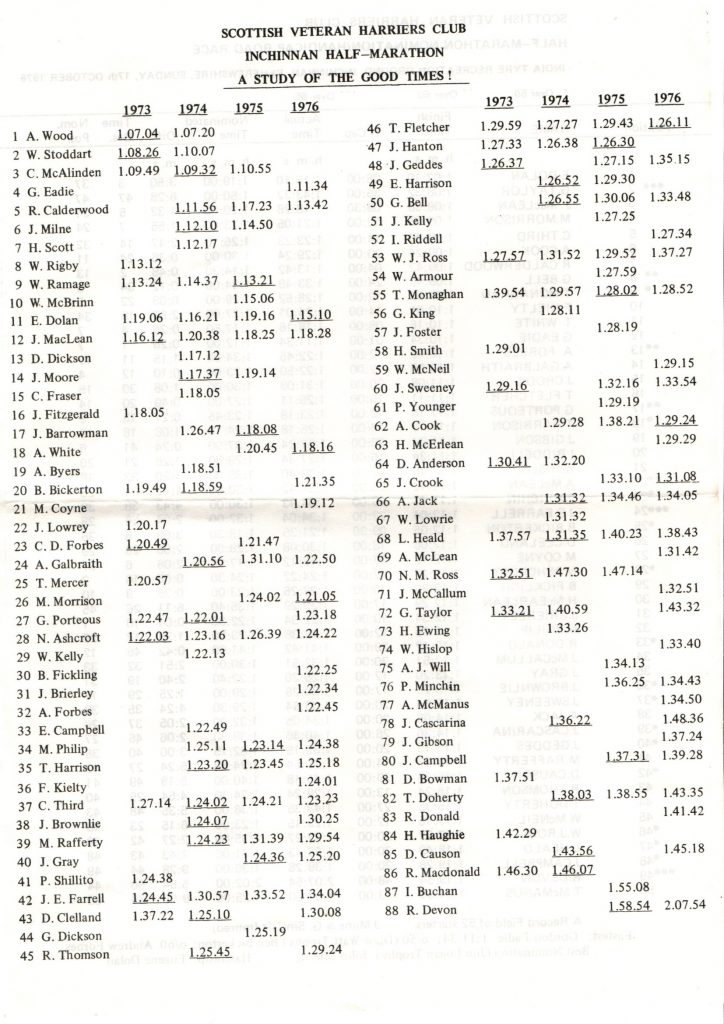

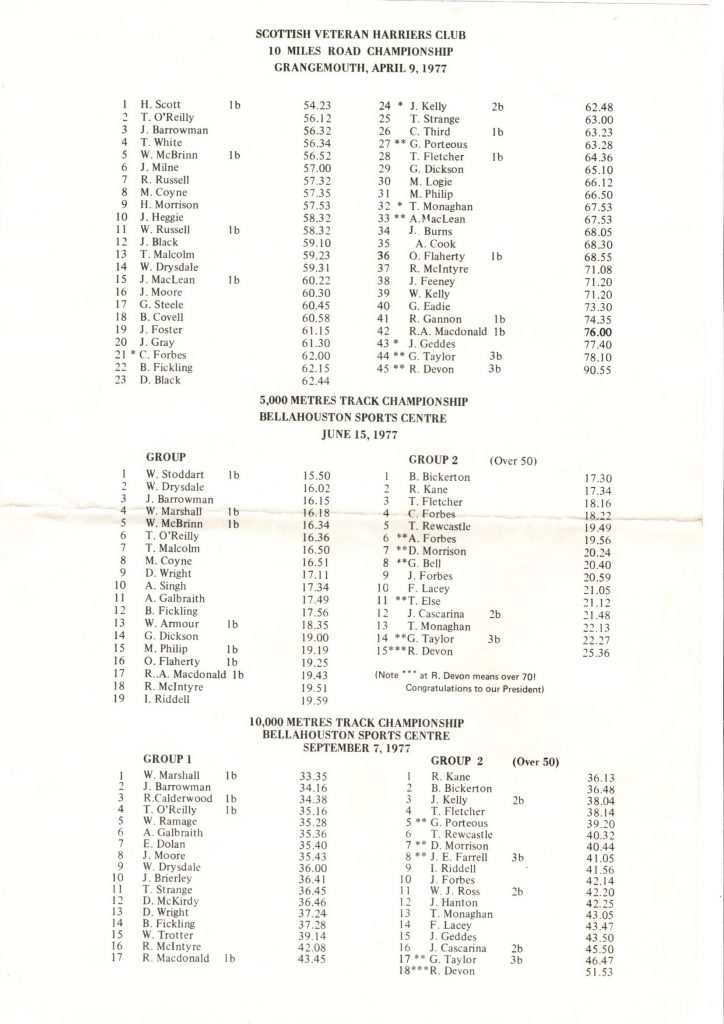

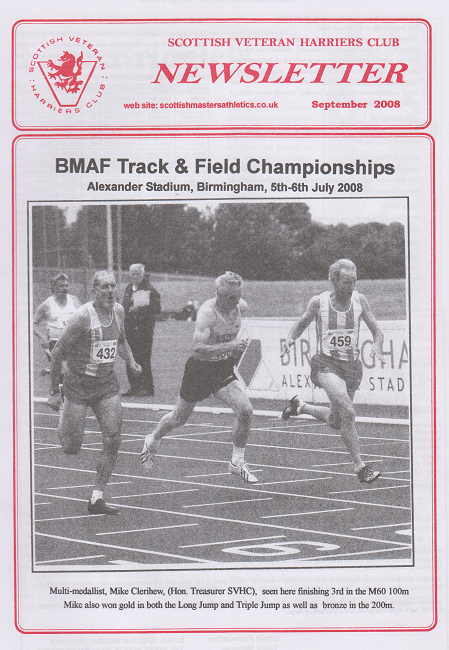

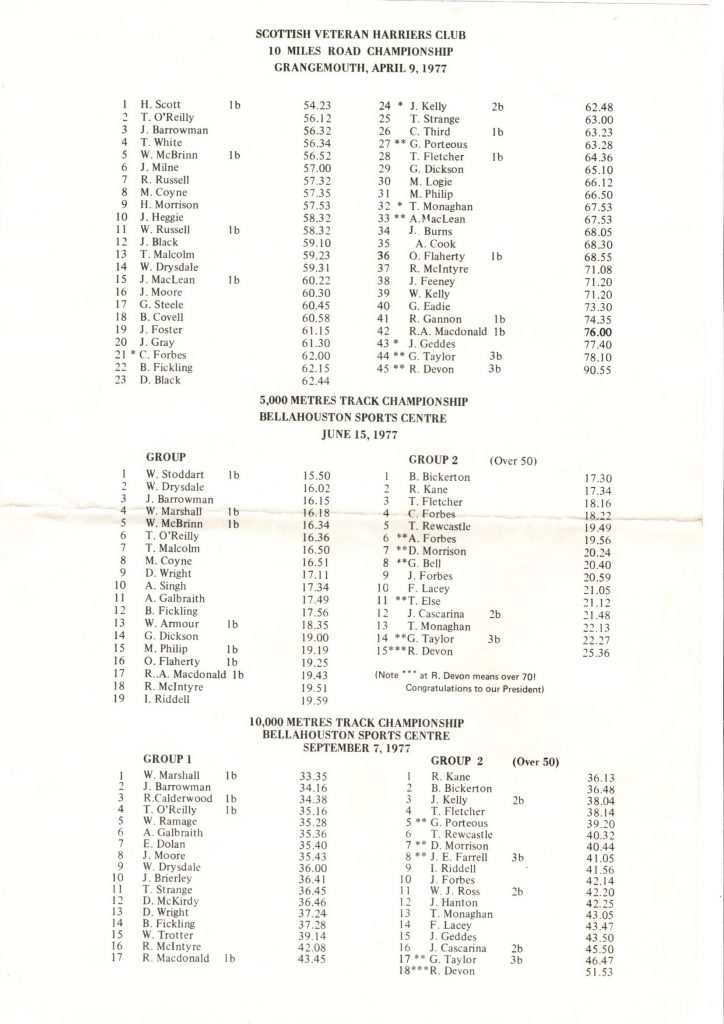

How has the fixture list changed? Well, less than might be imagined. From 1972 until 1984, the annual Scottish Veteran Harriers Open XC (for Men) was the Scottish Vets Championship; thereafter the SCCU took over. The list included: at least two other club cross-country races, a hill race; road races over 10 miles, half marathon and marathon; a road relay; the Christmas Handicap (over a distance of four and two-thirds of a mile), the Glasgow 800 road race; and Outdoor Track and Field championships. British Veteran events featured: XC (for Women too) and Track and Field (including 10,000m). Both European and World Veterans Championships had Track, Field, 10,000m, and Marathon.

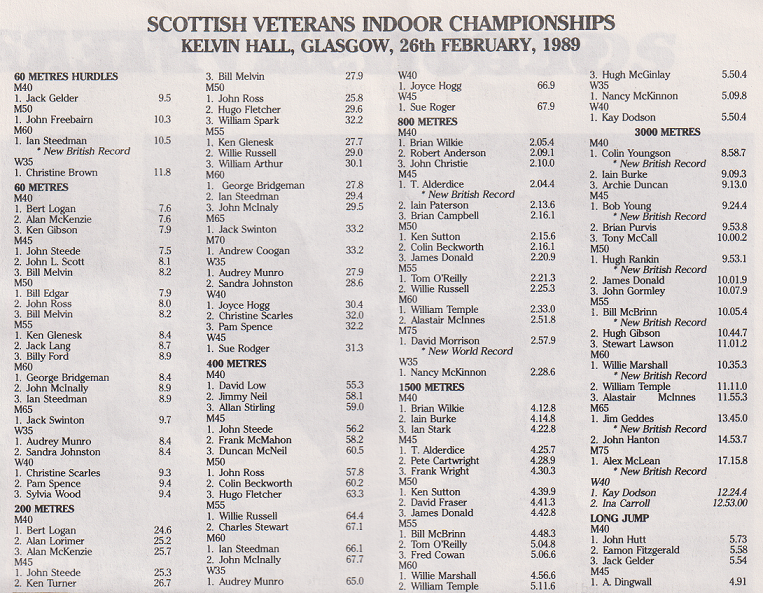

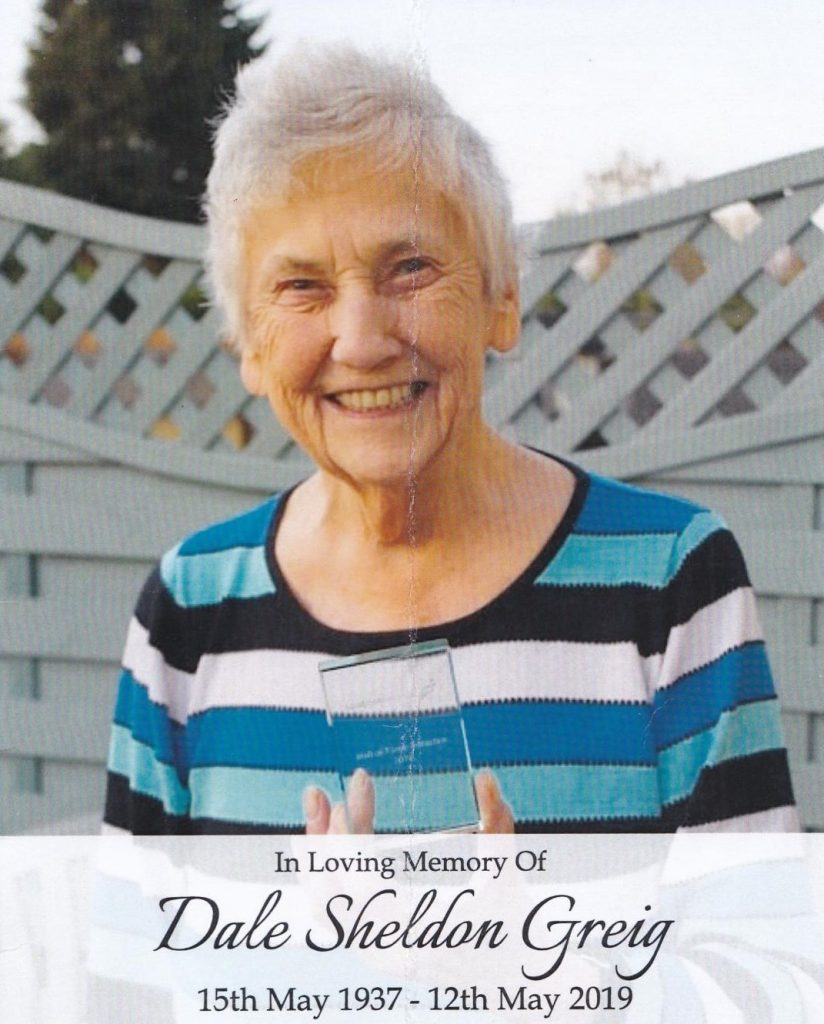

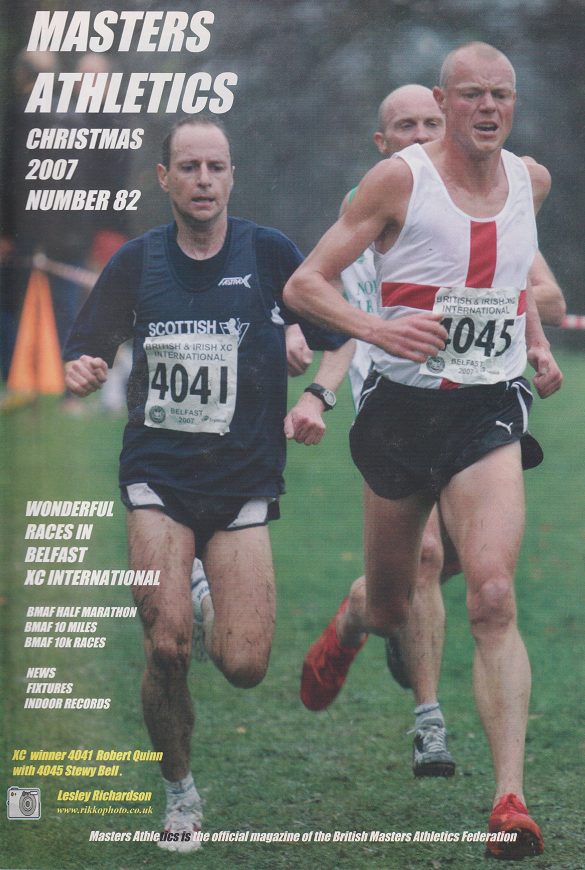

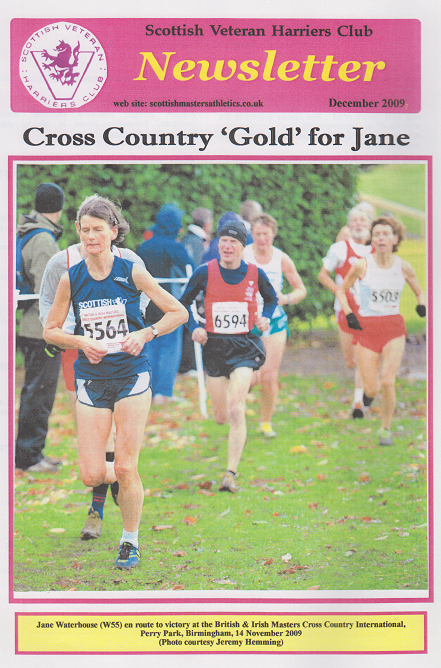

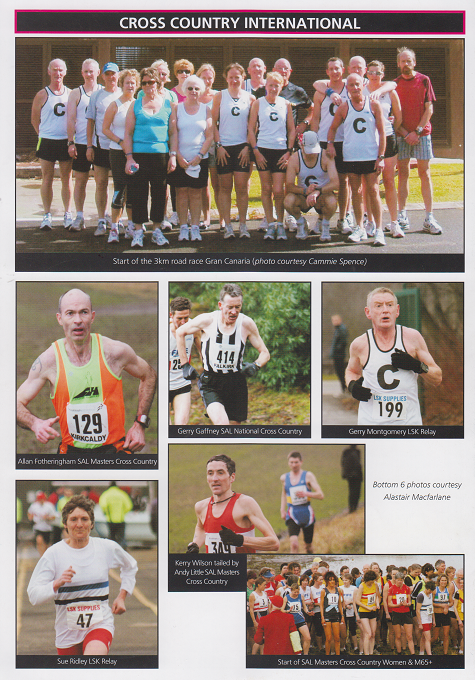

In 1988, the first Home Countries Veteran/Masters XC International took place; and this has developed into perhaps the most important race of the year for the fastest Scottish distance athletes. Certainly by 1989, the Kelvin Hall Indoor Track and Field allowed Scottish Vets to race on the boards, throw or jump, while sheltered from the elements.

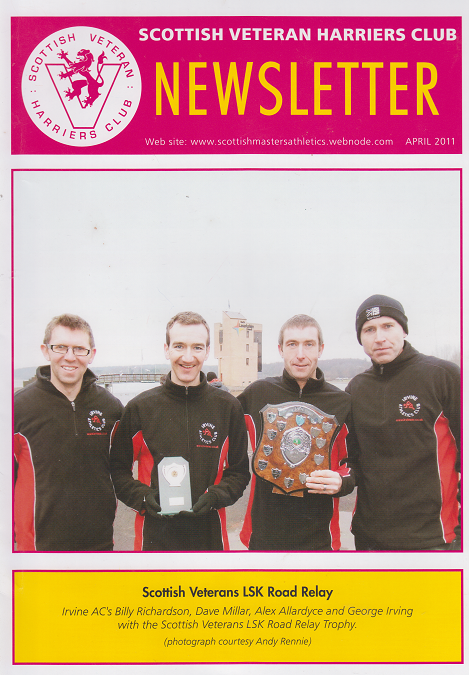

The 2019 fixture list contained: Christmas Handicap; Snowball Race; Cairnpapple Hill Race; SVHC 5k, 10 miles, half marathon, marathon, 10,000m; SAL Indoor and Outdoor Track and Field, Masters XC; BMAF road relays, 10k, ten miles, half marathon, marathon, XC; British and Irish Masters XC International; European Masters Outdoor Track and Field; World Masters etc etc. As I suggested above: FLOURISHING.

But let us not forget so many SVHC members, not only the champions but all the hard-working officials and everyone who trained and raced as well as they could, were as fit as possible in several age groups and who loved the ups and downs of a tough, rewarding sport. In another 50 years, I am optimistic that the Scottish Veteran Harriers Club, by this or a revised name, can reach its centenary!

N.B. Please note the following websites for a wealth of statistics and detailed reading:

* Scottish Distance Running History (especially The Veterans section);

* Anent Scottish Running;

*the Archive of the Scottish Road Running and Cross Country Commission; and

*the Scottish Athletics Archive (or Scottish Association of Track Statisticians).

THE BEGINNINGS

A veteran movement had been started in Germany to cater for long distance runners in the older age bracket, named IGAL for short. Its idea was to foster the love of distance running for its own sake over path, road and field but even masters or veterans have not entirely lost their competitive urge and inevitably it was mandatory to promote annual road races at 10 kilometres (six and a quarter miles) and 25 kilometres (fifteen and five eighth miles) and in alternate years 10 kilometres and the full marathon distance. A few years later a world veteran movement was formed, the WAVA, setting up a programme involving all athletic track and field events like a minor Olympic Games for older athletes to be held every two years. The age categories were over forty for men and thirty-five for women. Eventually it was agreed that groupings should be in five year periods. Even five-year groupings are arbitrary but perhaps as practical as possible.

In 1970 Walter Ross was instrumental in starting and developing a Scottish veteran movement. At first it was almost like a family gathering of older runners but later it spread in numbers and in competitive intensity.

John Emmet Farrell

Perhaps the best account of the club’s origins comes from the late Jack MacLean, a real stalwart and a founder member of SVHC. There follows an excerpt of his profile from the website Anent Scottish Running.

The club in which Jack has been most active is the Scottish Veteran Harriers Club, of which he (used to be) the only surviving founder member. The other members of the group were Walter Ross of Garscube Harriers, Jimmy Geddes of Monkland Harriers, George Pickering, Roddy Devon of Motherwell and Johnny Girvan of Garscube. How did that come about?

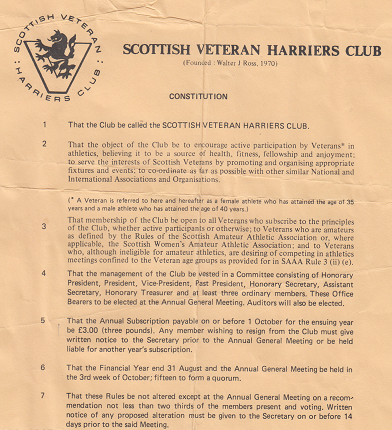

After the Midland District Cross-Country Championship at Stirling University in 1970, Walter Ross spoke to me. He wanted to form a Veterans club with a minimum age of 40 years, and paid me the compliment of being one of the enthusiasts of the game. The committee was formed of Walter and six others, and we held our meetings in Reid’s Tea Room in Gordon Street with a regular starting time of 7:00pm. We all put forward our ideas and Walter drew up a constitution. In the beginning the age groups went up in ten-year intervals.

I organised the very first Veterans race: the SVHC (Club Members only) Cross Country Championships. It was in Pollock Estate on Saturday 20th March, 1971 (i.e. in the 1970-71 season). We had very few officials at that point: Davie Corbet of Bellahouston started the race and shouted the times to George Pickering of Renfrew YMCA. I had laid the trail in the morning with markers of wee pegs with paper attached. 33 runners started and 32 finished. As I worked in the “Daily Record”, I arranged for a reporter and a photographer to attend. There was a wee piece in the Daily Record about it.

I organised the very first Veterans race: the SVHC (Club Members only) Cross Country Championships. It was in Pollock Estate on Saturday 20th March, 1971 (i.e. in the 1970-71 season). We had very few officials at that point: Davie Corbet of Bellahouston started the race and shouted the times to George Pickering of Renfrew YMCA. I had laid the trail in the morning with markers of wee pegs with paper attached. 33 runners started and 32 finished. As I worked in the “Daily Record”, I arranged for a reporter and a photographer to attend. There was a wee piece in the Daily Record about it.

The race was run over about 5 miles and the winner was Willie Russell of Shettleston. He was followed by Hugh Mitchell, Willie Marshall, Tommy Stevenson, Willie Armour, Chic Forbes, Jack McLean and Andy Forbes in that order. Andy Forbes won the Over 50 title from Tommy Harrison and Walter Ross. John Emmet Farrell was first Over 60, in front of Harry Haughie and Roddy Devon. Shettleston Harriers won the Team Award.

Within a year we had 1000 members from the whole of Scotland. Internationally we had great success as a small country.

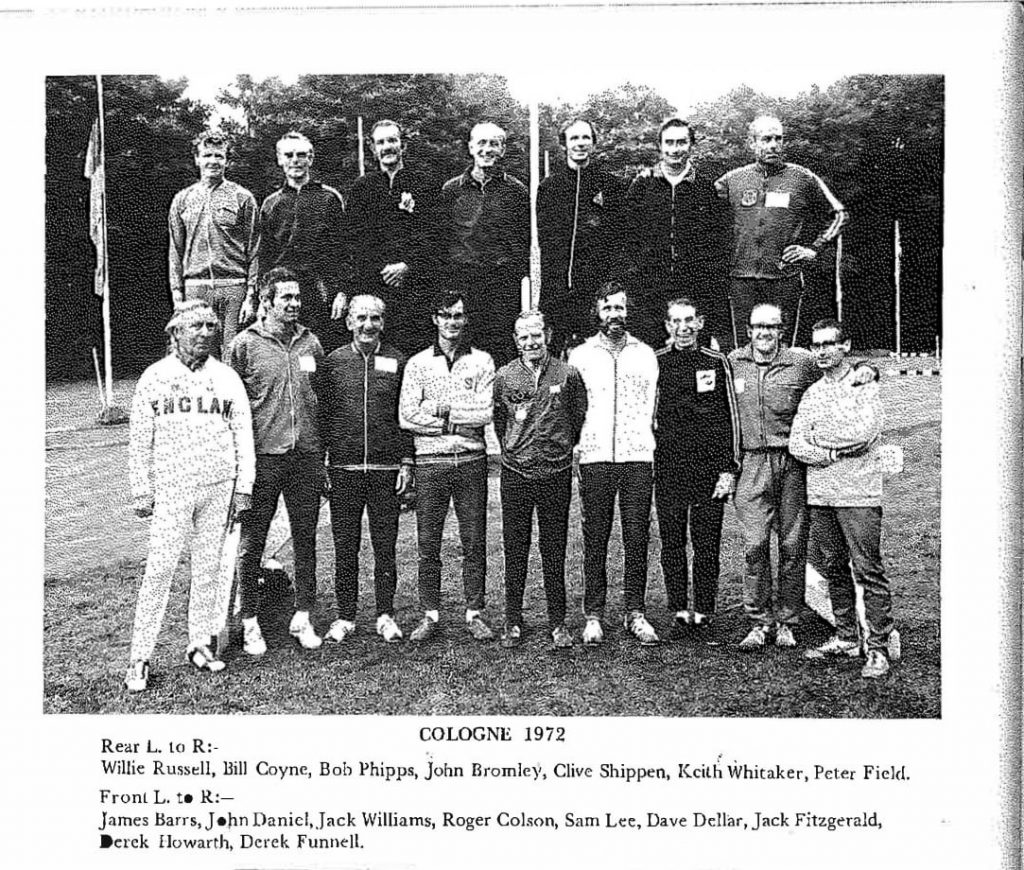

- In Cologne 1972 I ran the World Masters marathon, Bill Stoddart ran in the 10,000m. The Australians were boasting that they had the certain winner in Dave Power, double gold medallist (six miles and marathon) in the Empire Games in Cardiff. Bill Stoddart beat Power in just over 30 minutes.

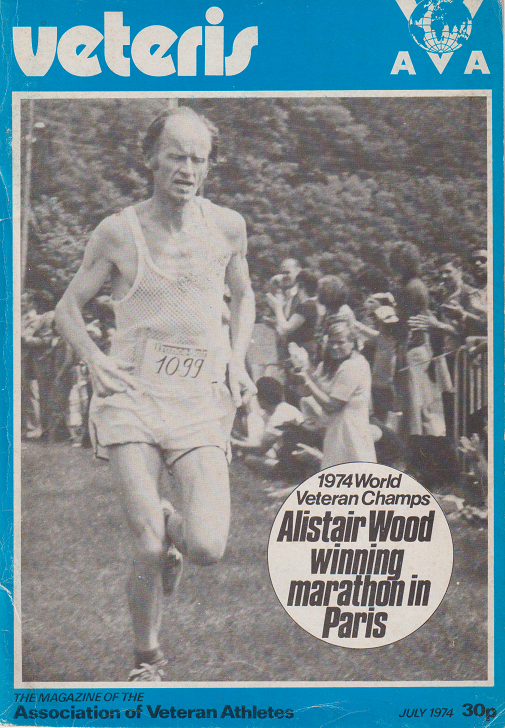

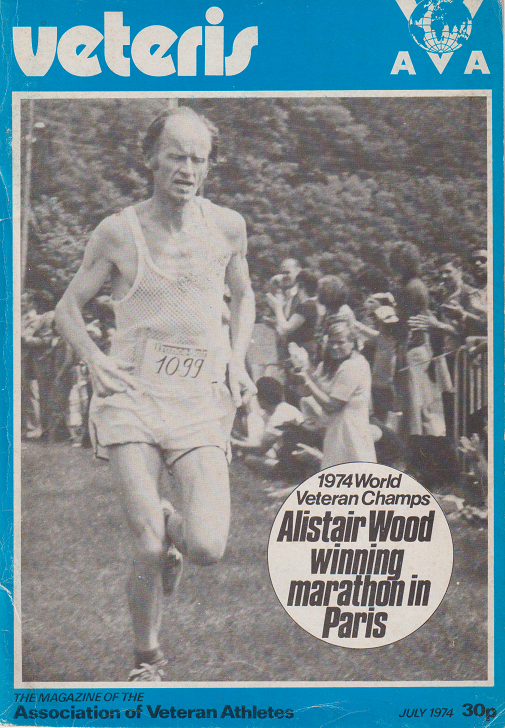

- Walter organised a large group to go to Paris for the World Masters Marathon in 1974. There were between 600 and 700 runners. On a day that was great for the spectators with a temperature of 88 degrees and not a cloud in the sky, Alastair Wood won the men’s marathon in 2:28:40 and Dale Greig won the Ladies marathon (Dale went on to compete in 10 IGAL Championships and three European Championships: and is now in the Scottish Athletics Hall of Fame.)

Charlie Greenlees of Aberdeen was 23rd and I was 33rd. We won the team race and I was 7th British runner to finish.

-

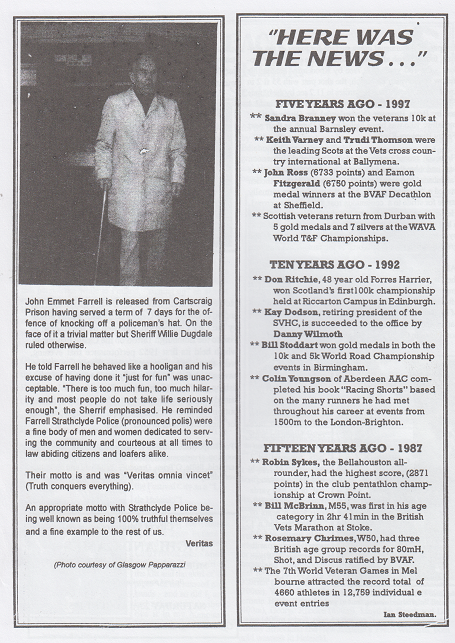

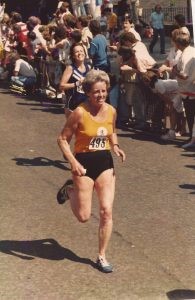

- Left to Right: Dale Greig and Aileen Lusk

- In 1980 the Scottish Vets staged the World Championships for 10,000m and the marathon. I, along with Willie Armour set out the course: Willie in his car with the clipboard, me walking with a surveyor’s wheel measuring the course. On the day, the whole thing went off very well with the Glasgow Corporation giving a great meal to the competitors in the City Chambers.

- Donald Macgregor won the M40 Marathon title.

Donald Macgregor

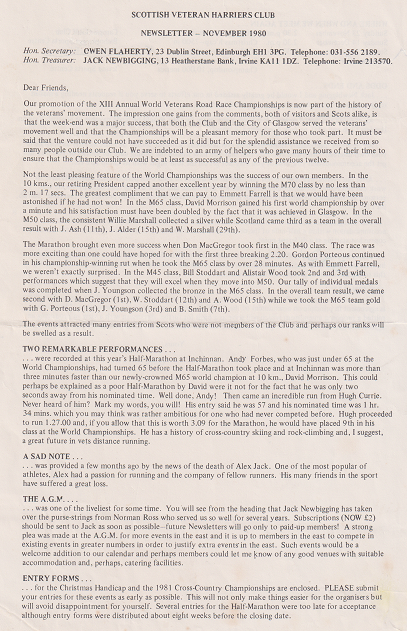

Having been one of the founding members of the Scottish Veteran Harriers Club, I served on the Committee for 10 years before giving it up. One of the unsung pillars of the organisation was Dale Greig. She worked for Walter in his printing business and, as well as typing the newsletters, she did a tremendous amount of work behind the scenes. (Walter and Dale certainly produced many Newsletters – although others contributed a lot – and subsequent editors included: Owen Flaherty, Henry Muchamore, Jack Newbigging, Kay Dodson, David Fairweather, Colin Youngson and Paul Thompson.)

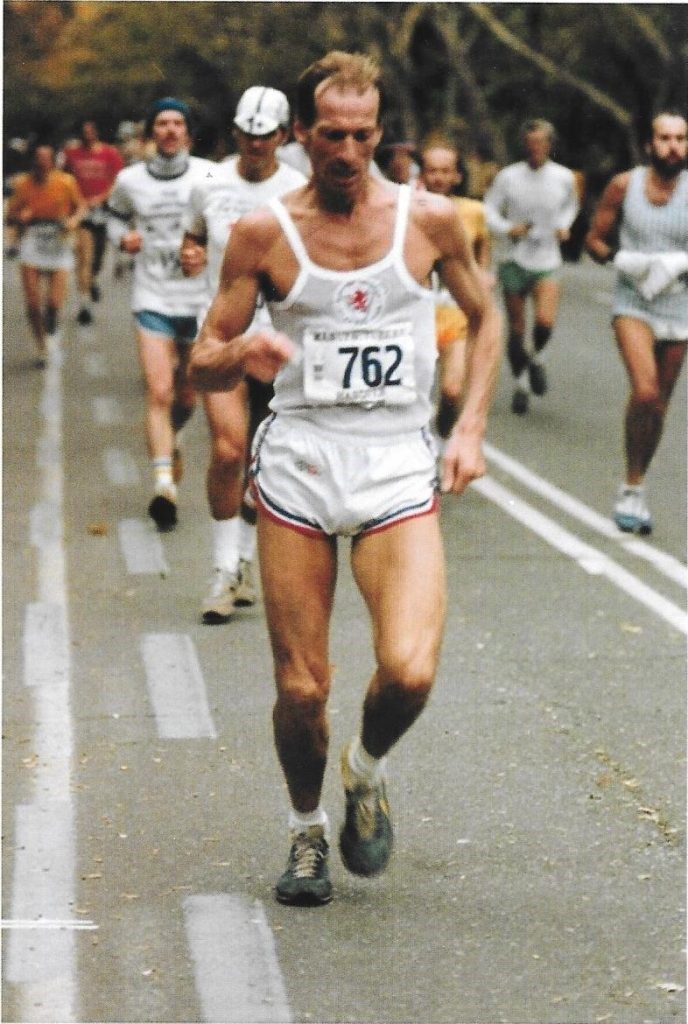

Jack (in an SVHC vest) with 200 yards to go in the 1980 New York Marathon where at the age of 51 he ran a time of 2:55

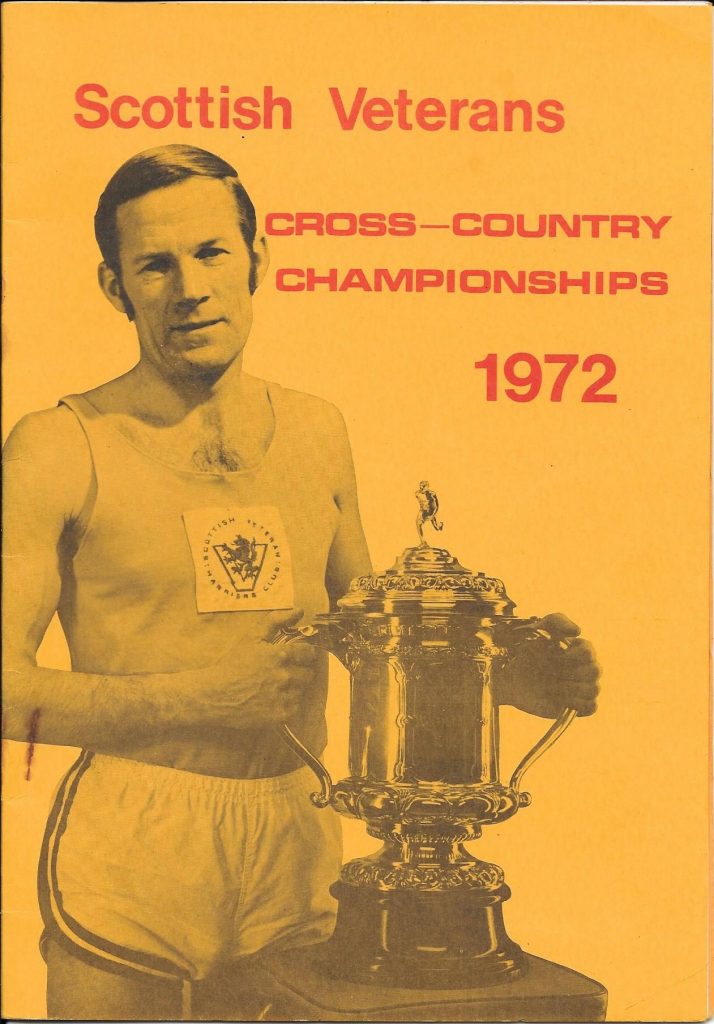

SCOTTISH VETERANS CROSS COUNTRY CHAMPIONSHIPS

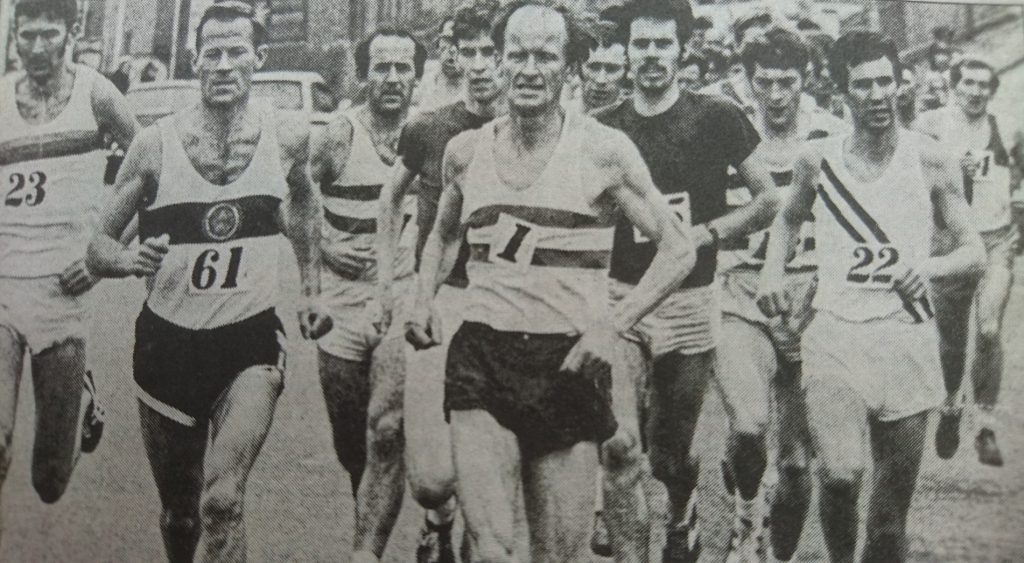

THE FIRST OFFICIAL RACE

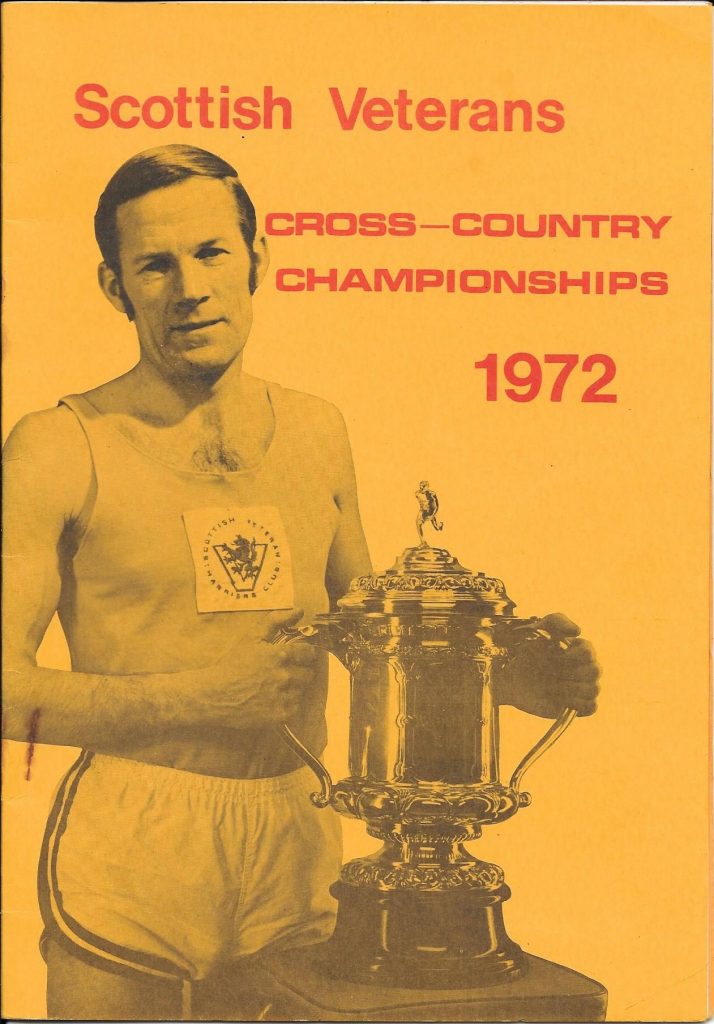

Bill Stoddart with the British Veterans Cross Country Trophy. He defeated England’s Arthur Walsham by thirty seconds. In 1972 he became the first Scot to win a World Veteran Championship: 10,000m in Cologne.

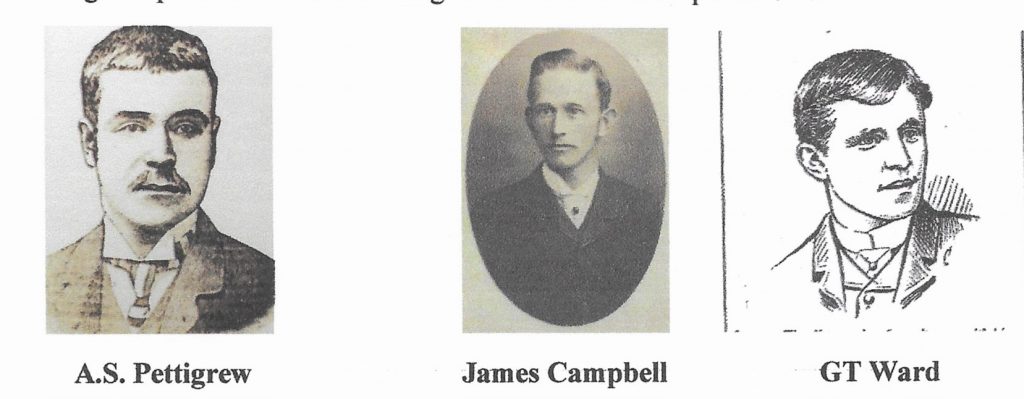

The second Championship (i.e. in the 1971-72 season), this time officially recognised by the Scottish Cross Country Union, was on 4th March 1972, at Clydebank, Dunbartonshire. The course was five miles (or eight kilometres) long. The SVHC organised the event, assisted by Clydesdale Harriers.

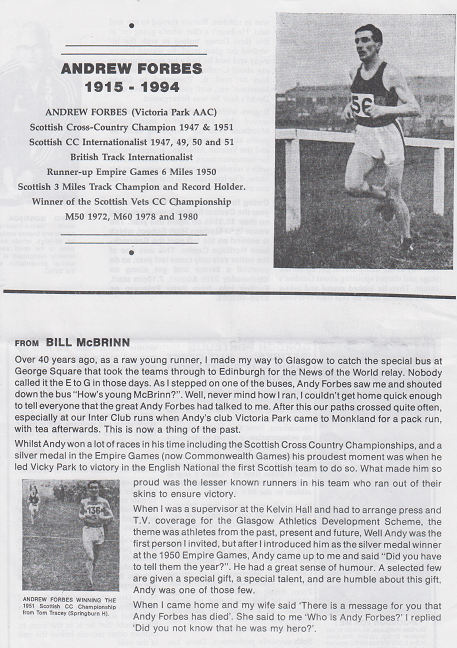

Bill Stoddart (Greenock Wellpark H) won easily, from Hugh Mitchell (Shettleston H) and Moir Logie (East Kilbride AAC). M50 champion was Andy Forbes (Victoria Park AAC), in front of Tommy Harrison (Maryhill H) and Walter Ross (Garscube H). Emmet Farrell (Maryhill H) retained his M60 title from Ron Smith (SVHC) and George Taylor (Shettleston H). Greenock Wellpark Harriers won the Team Award.

In the programme, Walter Ross, the SVHC Secretary, and a very important figure in the development of Scottish Veteran Athletics, published a poem (written many years earlier by an anonymous Clydesdale Harrier). Walter suggested it could be retitled ‘To a Veteran’.

To a Harrier

Some fellow men seem lucky, yet

I yearn to change with few,

But from my heart this afternoon,

I needs must envy you,

Mud-splattered runners, light of foot,

Who on this dismal day

With rhythmic stride and heads upheld

Go swinging on your way.

A dismal day? A foolish word;

I would not, years ago,

Despite the drizzle and the chill,

Have ever thought it so;

For then I might have been with you

Your rich reward to gain:

That glow beneath the freshened skin,

O runners through the rain.

All weather is a friend to you:

Rain, sunshine, snow or sleet.

The changing course – road, grass or plough –

You pass on flying feet.

No crowds you need to urge you on;

No cheers your efforts wake.

Yours is the sportsman’s purest joy –

you run for running’s sake.

O games are good – manoeuvres shared

To make the team’s success,

The practised skill, the guiding brain,

The trained unselfishness.

But there’s no game men ever played

That gives the zest you find

In using limbs and heart and lungs

To leave long miles behind.

I’ll dream that I am with you now

To win my second wind,

To feel my fitness like a flame,

The pack already thinned.

The turf is soft beneath my feet,

The drizzle’s in my face,

And in my spirit there is pride,

for I can stand the pace.

(Brian McAusland adds: a romantic view of cross-country, no doubt, but perhaps how we all feel, briefly, on a very good day! The first SVHC Cross Country Championship took place in 1971. We owe those pioneers a great deal.)

The ‘anonymous Clydesdale Harrier was Thomas Millar who had been club secretary for many years and contributed to the local Press under the pen name ‘Excelsior’. After being a member for decades he moved to the English Midlands which was where he sought work as an accountant. His son Gavin is a film director, BBC programme producer, director, actor and has been responsible for many excellent programmes.

(In the July 1992 SVHC Newsletter, the founder Walter J. Ross wrote the following, which makes clear how several important club members had been honoured for their invaluable services to running.)

IN THE PASSING

History moves on – and in the name of progress or otherwise there are bound to be changes. Whatever one’s views are of the reorganisation into one single Scottish Athletics Federation and the demise of the long-established ‘Governing Bodies’, there has to be some tinge of sadness at the winding up of the latter.

The Scottish Amateur Athletic Association and the Scottish Cross-Country Union have completed their centenaries.

However, on a nice note relating to the SVHC, it was pleasing that Danny Wilmoth, in the last year of the SCCU, was honoured as President (in 1996, for many years of excellent work for the SVHC, Danny was – unanimously – made an Honorary Life Member); and that John Emmet Farrell and Gordon Porteous were elected SCCU Honorary Life Members and presented with Scrolls. It is understood that there were only thirteen such elected persons in the 100 years of the SCCU and that includes our two Past Presidents Roddy Devon and George Pickering and also W.J. Ross. Ian Clifton, who has been a member of the Scottish Vets for some years, also gave great service to the SCCU as Hon. General Secretary.

It should also be acknowledged that in the Women’s movement, Molly Wilmoth has been a President of the Scottish Women’s Cross-Country Association; and Aileen Lusk was a past Secretary. Dale Greig – a behind-the-scenes activist for the Scottish Vets, had been Secretary, Treasurer, President and Life Vice-President.

We have also officials and members – too numerous to mention – who have given, and continue to give, much time and service to the whole sport.

Walter Ross was a wonderful man – friendly, gentle and a real enthusiast for the sport of athletics, in particular distance running. The articles and obituaries below will testify to that in better words than I can muster but I was fortunate enough to have met him many times and hear him speak in public at dinners and prize givings. I remember him speaking at a Clydesdale Harriers Presentation when he was guest of honour in the early 1970’s and, commenting on the novel concept of ‘fun-running’ as proselytised by Brendan Foster, saying “… but when was running not fun?”

I first saw Walter, as distinct from meeting him, when I turned up for my first ever county championships at the Brock Baths in Dumbarton. As we lined up on the Common for the start of the race, I saw this chap trotting across to the starting line with a young woman running beside him. Younger than he was, and taller than he was, it was Dale Greig whose marathon career he whole heartedly supported, indeed when she went to run in the Isle of Wight Marathon, she stayed with Walter’s brother. An excellent athlete on the track, over the country and on the road, a distinguished official and capable administrator, she worked with Walter on the ‘Scots Athlete’ magazine which he founded.

When the veteran harrier movement started up, he was the man who really provided the impetus to get the movement off the ground and keep the movement going until its impetus and sheer momentum kept it going.

Brian McAusland

However, we should look at his life in athletics and I reproduce the articles from his obituary and accompanying articles in the

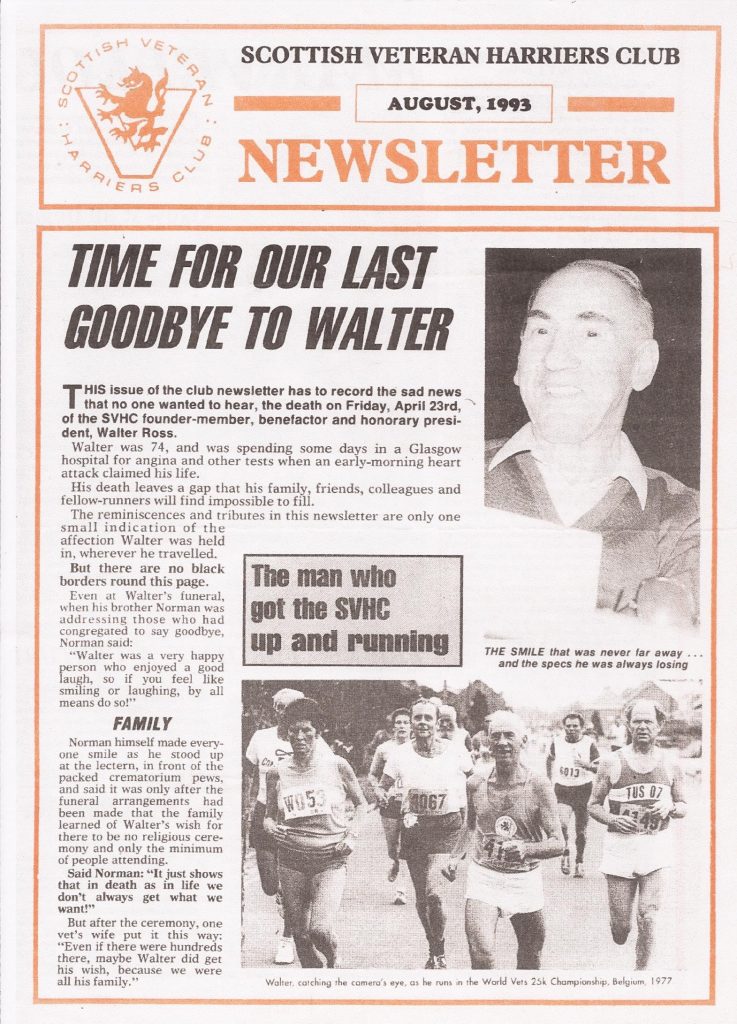

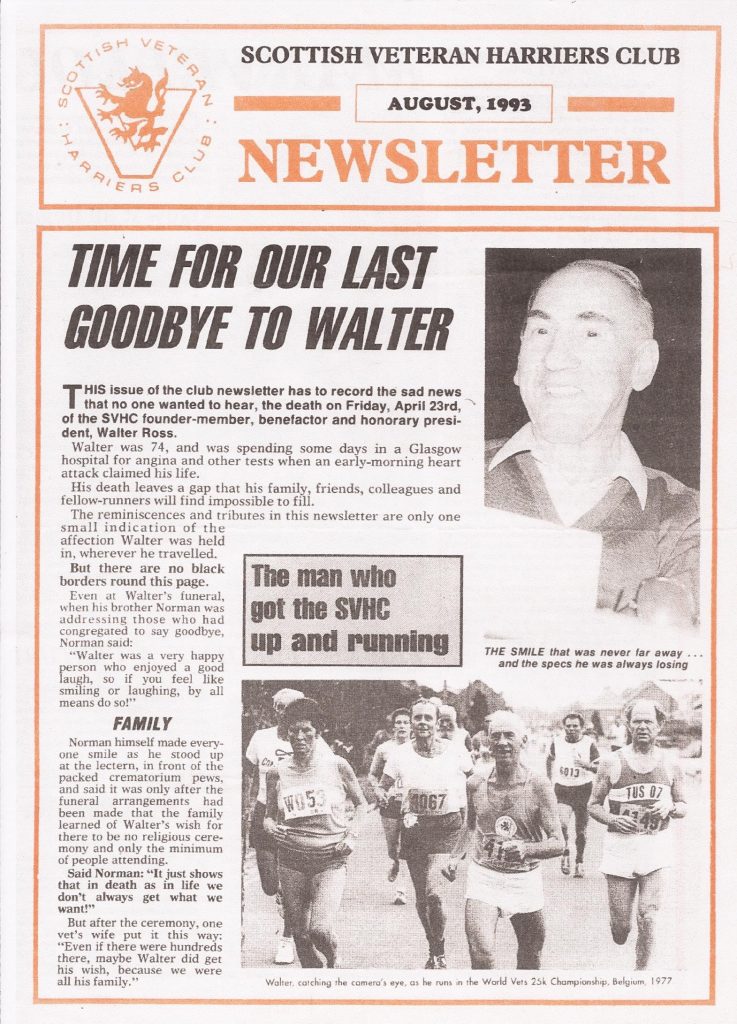

Here are some comments about Walter from his obituary edition of the SVHC Newsletter of August 1993.

Walter Ross – what a sad loss this man will be to Scottish Veteran Harriers. His generosity in providing printing services, including this magazine, prizes at races and gifts to the Ladies at Christmas will be greatly missed. Walter was very enthusiastic about Veteran Athletics and he spread his infectious enthusiasm and love of the sport throughout many countries worldwide, as he travelled to further the Veterans movement. He was a member of IGAL and set up world and European Championships in many countries. Walter’s other hobby was ballroom dancing and with his wife, Winnie, would give excellent demonstrations at many of the Veterans social functions. Walter printed ‘The Scots Athlete’ magazine in 1946 – before any other magazine in Scottish athletics was thought about. A man before his time, indeed.

Walter was never one to complain, although towards the end of his life, he was suffering. He still managed to travel to Birmingham to see the SVHC vest represented amongst the world’s Veteran movement. I personally will miss our chats in his office on a Friday morning. Often we would be discussing a problem and with his usual smile, Walter would say, “Don’t worry, it will work out all right on the day, don’t worry.” The Scottish Veteran Harriers will never forget Walter Ross. We are all indebted to Walter, both as a founder member of our club and for his loyalty, support and friendship over many years. Next year we plan to have a Memorial race and we are sure that club members will turn out to give something back to the man who started it all – Walter Ross.

Daniel Wilmoth, President SVHC

The Great Enthusiast

For the first time in years I know my telephone will not ring late tonight, previously a frequent feature of my evenings, for although I saw Walter at work every day, there would often be a late night call, an encore, an epilogue to the day’s activities; some business to discuss or just some piece of news or ‘tittle-tattle’ to impart. The silent bell, as the day ends, speaks volumes. More than anything it brings home to me the realisation that Walter J Ross, my long-time friend and colleague is gone, and that his voice will be heard no more.

Yet whilst mourning his death, those of us who knew him well will not lose sight of the important thing – that he did live, a life of struggle in many ways, but a life full of meaning. He has left all who know him and associated with him the memory of a true friend for whom service was more important than success and the joy and purpose of life. He was just 27 years old when he first published ‘The Scots Athlete’, regarded now as a great historical reference for the sport. Just as that publication was the articulation of the young man’s vision, so the founding of the SVHC in 1970 shows he still had the same vision and vigour when he had passed his 50th birthday. He had stayed the distance.

Walter was one of those mortals who never grows old. He retained that youthful enthusiasm, competitive spirit and robustness of purpose that was an inspiration to us all. His running activities took him all over the world, and when he wasn’;t competing in races he was ‘running’ them (!), the most notable being the World IGAL championships (10K and Marathon) which he brought to Glasgow in 1980.

“Nothing great was ever achieved without enthusiasm” (Emerson) was a bye-line that ‘The Scots Athlete’ carried for many years, Walter was enthusiasm personified in everything he tackled. He was a great champion too of women’s struggle for advancement, particularly in sport. When I helped found the Women’s Cross-Country Union in 1960, this too was Walter in the background with another of his ‘marvellous’ ideas!

I did not expect his life to end in the way it did. Unfortunately, death is no respecter of persons or age. As Omar says: ‘The moving finger writes, and having writ, moves on’. It is, knowing him, a happy thought that his courage, determination and mental vigour remained undiminished to the end. I last saw him some 36 hours before he died, when, ever the optimist, he asked me to make travel arrangements so that he could have a holiday when released from hospital! And so, at last, farewell, dear friend. But not to forget .. only a kind of chastened au revoir. In spirit you are with us always!

Dale Greig

(Dale, a fine Scottish International runner, worked as secretary for the editor and publisher, Walter Ross of ‘The Scots Athlete’ and then the typed up many SVHC Newsletters.)

FRIENDS FOR HALF A CENTURY

Having known Walter for over 50 years – even before I met my wife, Jean – it is no wonder that his passing has left me devastated. Walter showed his pioneering qualities by launching in 1946 ‘The Scots Athlete’ to which I made a monthly contribution under Running Commentary. The magazine was well-received and travelled to many countries. However, it was non-profit-making, and Walter’s principles wouldn’t allow him to take adverts for drink or tobacco. Sadly, it finally closed.

Gentle and endearing, Walter had the highest of ethical standards, especially if injustice was involved, or man’s inhumanity to man. His optimism was remarkable despite the stress of business and later, domestic duties. And starting up the Scots veteran athletic movement was an act of real citizenship. Walter admired the talented elite, but wanted sport to be for all. I’m sure many new adherents joining us for competitive or constitutional reasons do not know that this quiet, modest little chap was the cause of their new-found opportunity to enhance the quality of their lives.

From the approximate 12 apostles, the movement has now grown almost a hundred-fold. Robert Louis Stevenson said: “To miss the joy is to miss all.” Walter would have endorsed that.

In almost all strata, today’s world is very professionally-oriented or, to put it bluntly, MONEY-MAD!” But Walter, on the other hand was the supreme amateur. The multitude of veterans who run on country roads or woodland paths and grassy verges, rejoicing in the colour and poetry and space of the great outdoors, provide a living and vital memorial to a person for whom there is only one epithet. Unique.

John Emmet Farrell

Walter J. Ross, founder member of the Scottish Veteran Harriers Club, died on 22/4/93 at the age of 74 after a lifetime devoted to athletics. He ran with Garscube Harriers from boyhood until he was forced to retire at 64 with arthritis.

He was a life vice-president of IGAL unitl 1988, when it merged with WAVA. He edited, printed and published “Scots Athlete” from 1946-1960. His enthusiasm and organisation laid the foundations of Veteran Athletics in Scotland, and the present members owe a lot to his vision and example. He brought the World IGAL 10k and Marathon to Glasgow in 1980; and his trips to Vancouver, Perpignan, Bolton etc, will be long remembered.

Walter was unique in that he was the supreme optimist and enthusiast – we will miss his kindness and his contributions to our lives.

David Morrison

The Scottish Road Running and Cross-Country Commission Archive is an invaluable source of Championship results.

For the 1970s and 1980s the following Cross-Country information is listed:

In 1972, the Scottish Veteran Harriers Club introduced an open championship – effectively a Scottish Championship since it was open to non-members.

Cross-Country Championships for Veteran Women

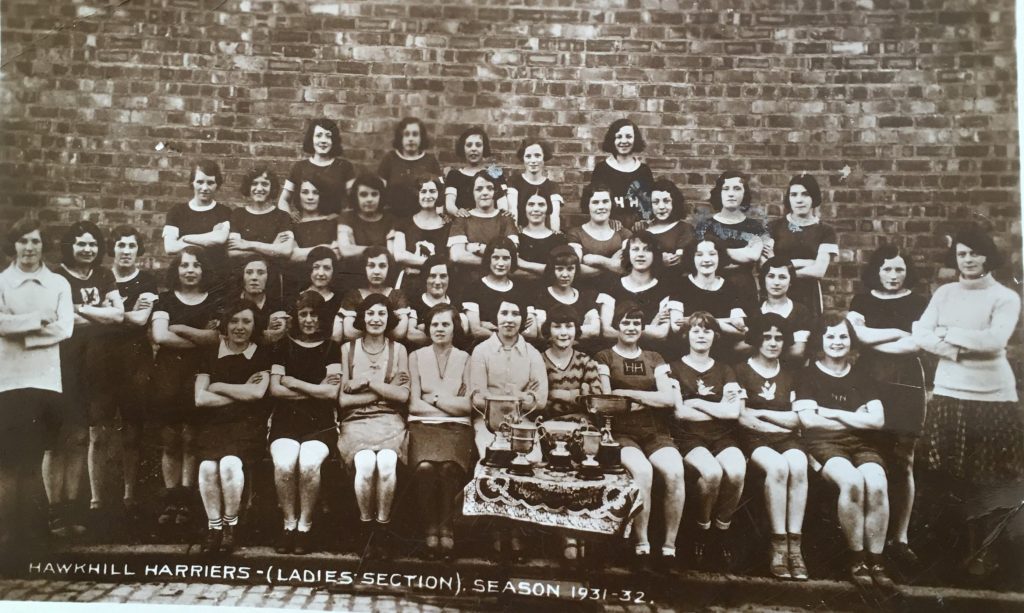

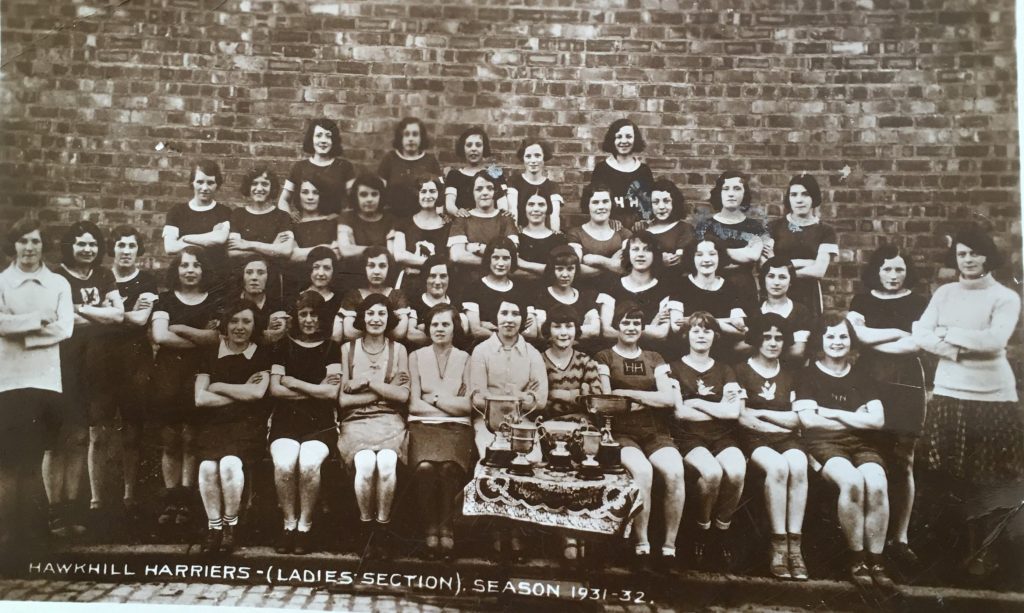

Dundee Hawkhill Harriers Ladies Section 1932. In the 1930s, Hawks were very successful in the SWCCU Championships – but no Veterans seem to be involved above.

Henry Muchamore remembers that one important thing he did with Henry Morrison and Ian Steedman in 1982/3 was to change the SVHC constitution to enable Female Veterans over 35 to become full members. However, their membership was slow to grow. Molly Wilmoth (wife of Danny) and Aileen Lusk were key in developing recruits. In late 1989, Molly Wilmoth [(nee Ferguson) a former Scottish cross-country internationalist and twice winner of the Scottish 880 yards title] became the first Female President of the SVHC, with Kay Dodson the Vice-President.

Here are a few landmarks:

In August 1980, Aileen Lusk finished third W50 in the IGAL (World Veterans) 10k Road Race in Glasgow.

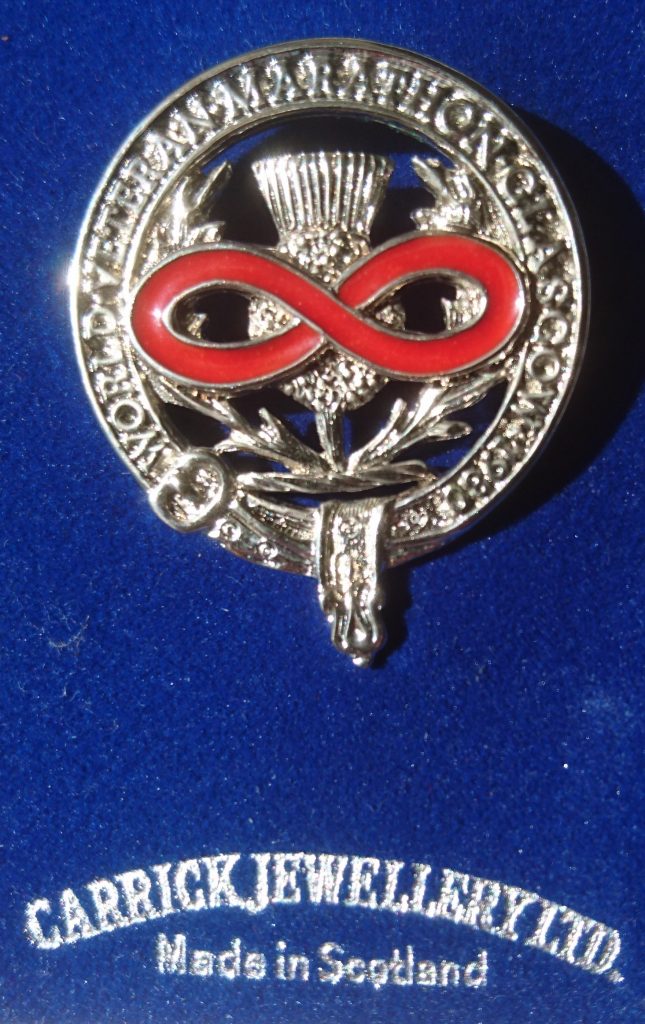

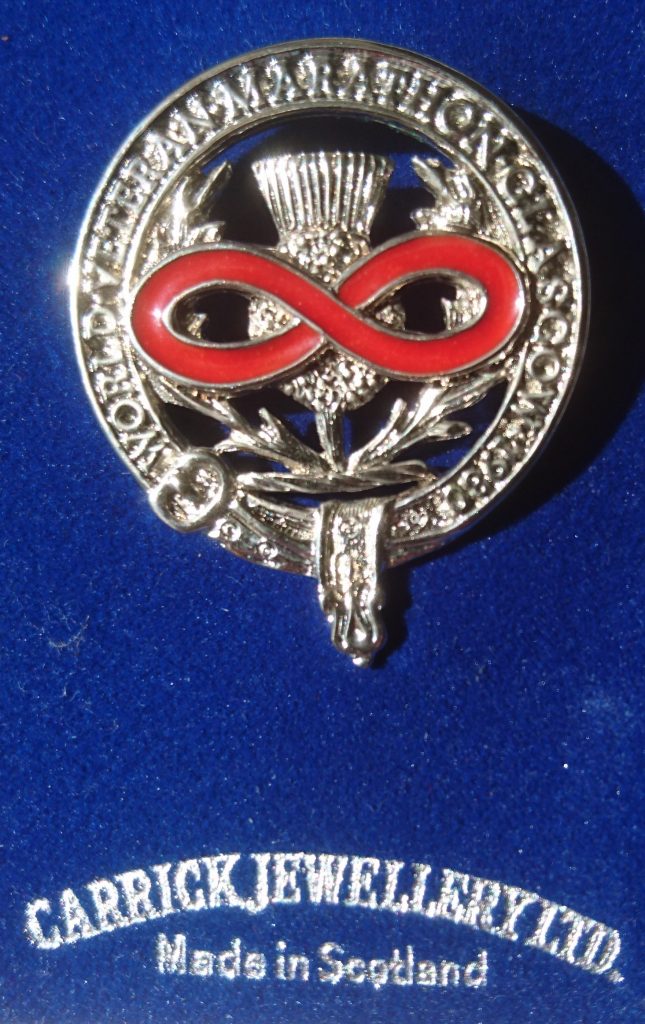

The Glasgow 1980 World Veterans Road Races medal

(Aileen said that she used to run with Dale Greig on Thursday nights in Bellahouston Park and it was Dale who encouraged her into vets racing and trying the marathon: the first was at Inverclyde where she suffered badly on a very hot day in August 1981 but she managed to finish first W50 in 3.45.36.)

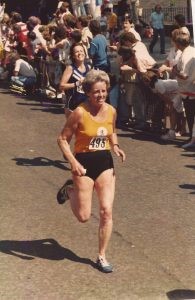

Left to Right: Dale Greig and Aileen Lusk

In late 1982, Aileen Lusk and Molly Wilmoth were the first two Women Vets to join the SVHC Committee. Four Female SVHC runners completed the Glasgow Marathon.

By early 1983, in the British Vets XC Championships, all Veteran Women ran with M50+ Men, over 5000m. Aileen Lusk (W50) and two younger ‘Lady Veterans’ completed the ‘Glasgow 800’ 6.6 Miles Road Race. Molly Wilmoth ran a 10k. Other Women completed Half Marathons.

A real pioneer, Aileen Lusk ‘a Scottish National mile and cross-country champion three decades ago, deservedly gained World Veteran medals for third place in both the 10k and 25k events in the W55-59 category.’ This was in the International Veterans (IGAL) road running championships (on the 15th and 16th October 1983) at Perpignan in the South of France.

(The Scottish Athletics Archive notes the following:

Aileen LUSK (1928-)

Club: Western

Born Aileen Drummond, she was Scottish WAAA 880y champion in 1954 & 55, Mile Champion in 1953, 54 and 55, and Cross-Country champion 1954 to 1956. During 1954-1956 she ran for Scotland once on the Track and three times over Cross-Country.

1967 1 Mile 5.57.7 ranked 7th

1969 1500m 5.17.11 ranked 5th

1971 1500m 5.54.42 ranked 8th

1971 3000m 12.31.2 ranked 11th)

In 1984, Helen Fyfe, Mary Houston and Mary Marshall ran the Tom Scott Veteran 10 Mile Championship in April. Aileen Lusk completed the SVHC 10,000m track. She finished behind Helen Fyfe in the club Half Marathon but in front of three other Women; Margaret Robertson ran fast in a 1500m Time Trial.

The track season review included the following: “In the women’s events, the number of entrants is still small, but a start has been made, and next year we can expect a fair increase in numbers. In the 100 and 200, Katherine Laing gained a double; as did Molly Wilmoth in the 400 and 800; and Hazel Stewart in the discus and javelin. Aileen Lusk ran a tremendous 5000m in 22.48.6, which must be at least a British W55 best.”

In June 1984, Aileen recorded 45.21 to win her age-group in the inaugural ‘10K-OK’ women-only race in Glasgow

In June 1985, at Lytham St Anne’s, Aileen Lusk added another bronze medal in the W55-59 category of the 10k race which was part of the IGAL World Veterans Road Championships.

In the Christmas 1986 Newsletter, Molly Wilmoth wrote:

“As a lady veteran, a Committee Member and also the wife of your membership secretary (Danny), I decided it was about time to put the spotlight on our lady members.

From the membership roll, I see that a large percentage is female – 17 new members in the last three months alone.

So what we have to do now is get the pleasure of meeting each other.

New members can have a shyness, a feeling of wondering what kind of reception they’ll get turning up for a race, maybe a fear of being too slow to compete.

Honestly, there’s no need to worry. And from all accounts, lady vets in the north-east are discovering that fast.

One suggestion I’d like to make is that we have a meeting of females only. We could have a pack run, followed by a cup of tea and a chat.

This would let us meet one another, and discuss how we can strengthen the female numbers at veteran races.

So my message to all lady members of the SVHC is to forget your doubts and let’s meet.

If you’re interested in a Ladies Day, please give me a ring any time after six o’clock (in the evening!).”

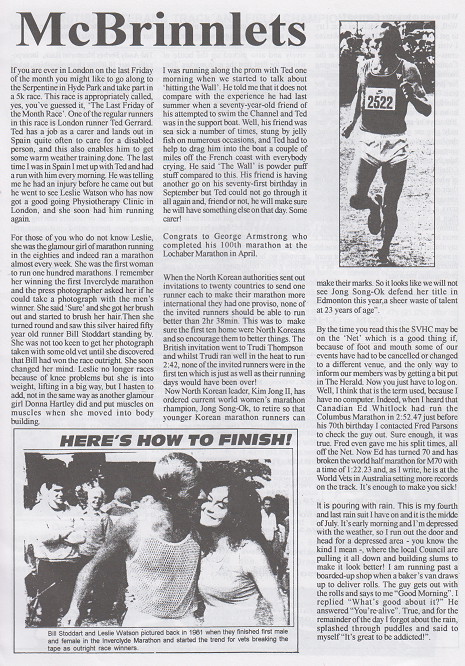

In the 1987 Glenrothes Half Marathon, when 1500 took part, W35 Jacqui Ferrari of Pitreavie finished first overall, and thus emulated Don Macgregor, Bill Stoddart and the renowned female marathoner Leslie Watson, who previously had all managed to win a road race outright, as well as being first Veteran.

It seems likely that from the early 1970s, taking part as guests, one or two Women Vets (mainly W35 or W40 for a start), might run in SVHC XC events. Kay Dodson remembers taking part in several, mainly in the Central Belt : for example, on 1/12/85, 30/11/86, 17/1/88, 15/1/89, 14/1/90, 20/1/91, 22/12/91.

On 19/11/79, at Lochinch, Aileen Lusk was first W50, recording 39.13 for 5 Miles.

In 1987 at Dumbarton, over a 4000 metres course, Kate Chapman of Giffnock North was first W35 in 15.06, from Susan Belford (Kilbarchan) 16.04 and Jane Murray (Kilbarchan) 16.10.

On 17/1/88 at East Kilbride, Sue Belford (Kilbarchan) was first W35; Kay Dodson (Law) first W40; and Margaret Moore (Kilbarchan) first W50.

In 1989, Kate Chapman was first W35, from Kate Todd and Jane Murray; Kay Dodson won W40; Margaret Robertson W45; and Margaret Moore W50. The distance was 5 Miles, and Men and Women raced together.

In 1991, Janette Stevenson (W40) was first home; followed by Rose McAleese (W35). Jackie Byng won the W45 category; Margaret Robertson W50; and Margaret Moore W55.

In 1992, Janette won W40 again; Janet McCall W35; and Margaret Moore W55.

At some time, probably in the mid-70s, an annual W35 contest commenced, which was part of the Scottish Women’s National Cross-Country Championships, organised by either the Scottish Women Veteran Runners Association or the Scottish Women’s Cross Country Union and Road Running Association. (Dale Greig had been Senior National Champion four times.) The Scottish Senior Women’s Cross Country Championships started in 1932, continued until 1938; then restarted in 1950.

Henry Muchamore (who was SVHC General Secretary until 1985 then Vice President for a year before becoming President in 1991; and ran for Scotland as an M50 in the 1991 Cross Country International at Ampthill), added:

“The WCCU did not recognise FV age group categories (until 1984?). Only after much debate did the SCCU agree to adding one Veteran (now Masters) W35 age group in their Women’s Senior XC Championships. Now (2020) we have ALL Male and Female Age Groups included in the SAL Vets XC championships. It was a tough road to negotiate this, and in parts a ‘quagmire’ but we got there in the end.“

Records are incomplete; and races often badly reported, with Veterans omitted.

Here is what can be found in the Glasgow Herald or Athletics Weekly or the SVHC Newsletter between 1975 and 1992. (There are much better results from Season 1992-93 onwards, when proper Combined Male and Female Veteran XC Championships started.)

1974-5 on 2nd March at Dalkeith: Norma Campbell (Blaydon H) 22.12, Noreen O’Boyle (Victoria Park AAC) 23.21, Dale Greig Paisley H 25.51, Aileen Lusk (West) 27.06, M Steel (Paisley) 27.45, R Docherty (Greenock) 28.39.

(Norma Campbell was actually 46 years old.)

(This 1975 race was the inaugural Scottish Women Veteran Runners Association championships, organised by ”that well-known marathon and cross-country runner” Dale Greig. In 1976 and 1977, this event was held at the same venue and day as the Scottish Veterans XC Championships, but over a shorter course than the men ran.)

1975-6 No SWVRA result has been found, but first Veteran in the SWCCU championships was Dale Greig, closely followed by Noreen O’Boyle.

1976-7 on 5th March at Coatbridge: Pearl Meldrum (Grangemouth) 21.15, Norma Campbell Berwick AC, 22.38 Dale Greig Paisley H 23.53, Aileen Lusk (Bishop) 24.29, E Steedman (Edin) 24.36. (The second and last result found for the SWVRA championships.) In the previously held SWCCU event on 19th February at Dumbarton, Pearl Meldrum was first Vet (and part of the winning Glasgow AC Senior team); with Dale Greig second Vet.

1977-8. There is no AW result for the SWCCU event. However, at Glasgow, in the SWCCU 4000m Closed Cross Country championship (for Scots only), Pearl Meldrum (Glasgow AC) was first Vet.

1978-9 No SWCCU results found; but on 3rd March at Strathclyde Park, in the East v West XC, Pearl Meldrum finished 5th ‘Senior’.

1979-80 On the second of February 1980 at Lanark Racecourse, the former Scottish XC International and Marathon racing star, Leslie Watson, finished a good 10th in the SWCCU championships – alas, two days before her 35th birthday!

1983-4 at Beach Park, Irvine: Palm Gunstone (Dundee) 25.48, Pearl Meldrum (Grangemouth) 26.05, Margaret Robertson (Troon) 28.10 (Logically, between 1977 and 1983, Pearl Meldrum may well have been the best home-based Scottish Woman over-35 cross-country runner.)

It seems likely that this 1984 SWCCU National Championships was the first one to feature a W35 category. Further evidence which suggests that from this season onwards there was official recognition of leading Veteran finishers in Senior Championships is that, for the first time, Male Veteran winners were mentioned in the results of the: East District XC (Rod MacFarquhar of Aberdeen); West District XC (Lachie Stewart of Shettleston); and Home Countries XC International match at Cumbernauld (Brian Carty of Shettleston).

(However, the first Woman in the 1984 Scottish Veteran XC Championships, was Ina Robertson (Scottish Vets) in 44.08. She ran the whole 10k course with the Men. Not sure if this was ‘legal’ for cross-country at the time; although Women could certainly run with Men in road races like marathons.)

1984-5: Lorna Irving (ESH) was first W35 (in 4th place overall); and Palm Gunstone (DHH) second W35. (Lorna had recently won the Scottish Peoples’ Marathon in Glasgow and went on to represent Scotland and finish a very good sixth in the 1986 Edinburgh Commonwealth Games Marathon.)

1985-6 at Irvine on 23rd February: Kay Dodson (Law and District) 25.49, Jean Sharp (Central Region AC) 26.07, Pearl Meldrum (Grangemouth) 26.48

1986-7 at Cowdenbeath: Lorna Irving (Edinburgh Southern Harriers) finished first W35 in 9th place overall 25.39; 2nd W35 was Jacqui Ferrari (Pitreavie) in 26.52; and 3rd W35 was Kate Chapman (Giffnock North) in 28.48.

1987-88: on 28th February at Irvine, Heather Wisley (Fraserburgh) was first W35 (19th overall). (Heather was a former Aberdeen University squash ‘blue’ who took up running six months earlier, on reaching her 35th birthday.)

1988-9 at Irvine: Patricia (Tricia) Calder (EAC) 6th overall in 23.50, Janette Stevenson (FVH) 16th in 25.12. 1st Vet team: Giffnock North.

1989-90 at Bridge of Don, Aberdeen: Renee Murray (Giffnock N) 23.44, Ann Curtis (Livingston) 24.10, Margaret Stafford (Aberdeen AAC) 24.37. First Vet team: Aberdeen AAC.

1990-91: on 24th February at Irvine, Tricia Calder (EAC) was first W35 (7th overall); Janette Stevenson (FVH) second W35/first W40 (19th); and Jackie Byng (Irvine) third W35 (but first W45).

1991-2 Janette Stevenson (Falkirk Victoria H) 9th overall. (Christine Price, competing for Bolton, finished first Veteran in the English Cross-Country Championships.)

In addition, there was a W35 category, especially in the West District XC. On November 24th 1985 at Lanark racecourse, Kay Dodson finished 18th overall and won her age group.

1987: Kate Chapman (Giffnock North)

1988: Jean Sharp (Central Region AC

1989: Janette Stevenson (FVH)

1990: Rose McAleese (Monkland Shettleston)

1991: Janette Stevenson (FVH)

The only East Districts XC W35 result I can find is from 1988, when Liz Buchanan (Haddington) finished first.

The very first Veterans International Cross-Country Championships took place in 1988. Find a detailed summary of this great annual fixture in the Veterans Section of Scottish Distance Running History.

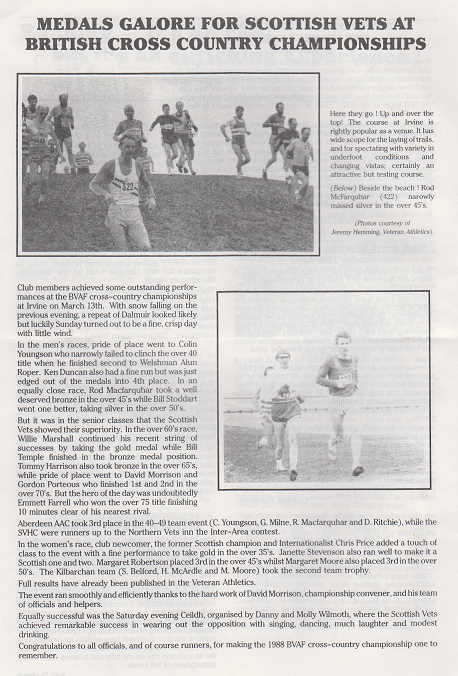

The British Veterans Athletics Association (BVAF) also organised XC Championships, in which M50 men raced against all Women Veterans over 5000m courses. For example, at Irvine on March 13th 1988, well-known Scottish International Christine Price won the W35 category, with Janette Stevenson second. Margaret Robertson won W45 bronze; and Margaret Moore W50 bronze.

Palm Gunstone who, in the 1970s, ran three times for Scotland in the World Cross, and went on to be the 1984 National XC W35 winner, remembers that there were differences of opinion in the Scottish Women’s Cross-Country Union. Some people thought 35 was too young to be a Vet and that the qualifying age should be 40, same as the Men. They also thought the distances were too short – 3 miles was the longest cross-country for Women in the 70s and early 80s; with 4000m being the usual distance.

Palm ran what she thinks was the first SWCCU Women’s Road Race Scottish Championships (over 10K) in Glasgow in 1984. Liz McColgan won the race and Palm was 1st Vet.

Therefore, during 1975-1992, it seems that Women Vets could not race officially on the same day and at the same venue as the Men’s Scottish Veterans XC Championships over 10K.

From Season 1992-93, under the newly-formed Scottish Athletics Federation, Women Vets had a separate race at the same venue and on the same day as the Scottish Veterans XC Champs, in five-year age groups up to W55 (nowadays, in 2020, W75).

The distance that Veteran Women raced had increased to 6k; which nowadays is also the 5 Nations Masters International XC distance, although in the Scottish Masters XC Champs the Women still have a separate race; in the International, the Women run (and ‘murder’) the over-65 Men.

Weirdly, in the Scottish Vets XC, there was a W35 category from 1993 to 2013; but from 2014 this changed to W40 and upwards. Briefly, between 2006 and 2013, there was also an M35 age group but since then, only M40 and upwards. Yet, in the 5 Nations International, there are both W35 and M35 contests!

In 1985, the Scottish Cross Country Union introduced a Scottish Veteran Championship (over 40, over 50 and over 60), for Men, for individuals with a single combined team race. Initially these races were held in conjunction with the Scottish Veteran Harriers Club races. (Between 1985 and 1987, the SVHC presented medals for the M45, M55, M65, M70 and M75 age-groups; then the SCCU presented these medals from the 1988 Championships onwards.)

M40

1971-2 William Stoddart Greenock Wellpark H 29.52 Hugh Mitchell Shettleston H 31.27 Moir Logie East Kilbride AAC 31.49

1972-3 William Stoddart Greenock Wellpark H 28.41 Charles McAlinden Babcock & Wilcox AC 29.20 Tom O’Reilly Springburn H 30.22

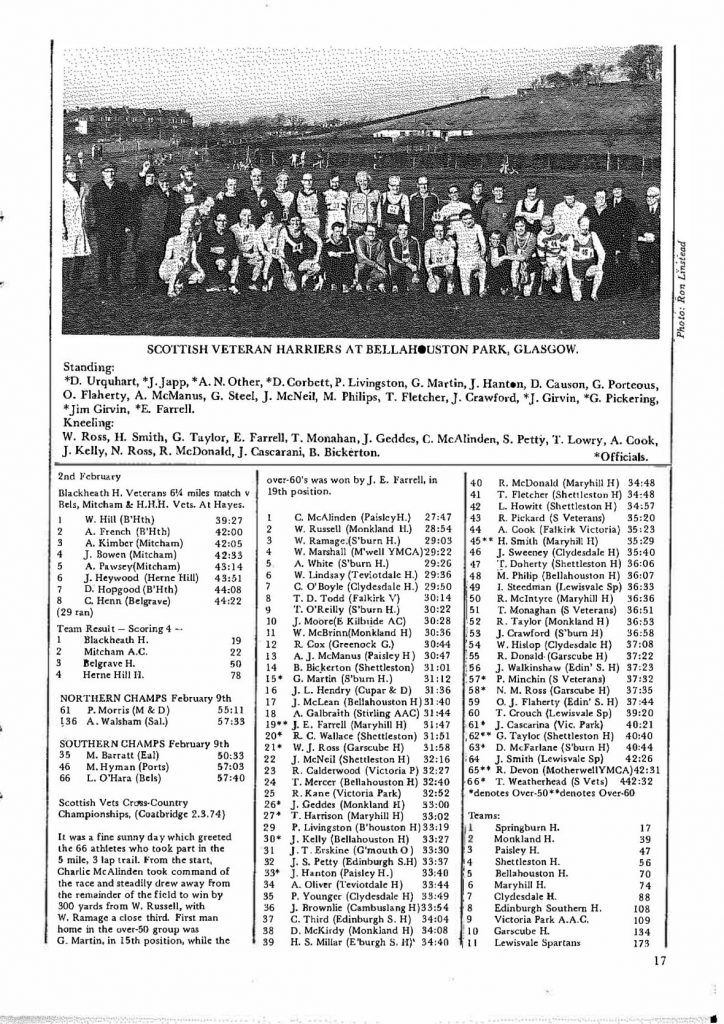

1973-4 Charles McAlinden Paisley H 27.47 William Russell Monklands H 28.54 William Ramage Springburn H 29.03

1974-5 Charles McAlinden Paisley H 28.52 Gordon Eadie Cambuslang H 29.41 Jim Irvine Bellahouston H 29.42

1975-6 Charles McAlinden Paisley H

1976-7 William Stoddart Greenock Wellpark H 29.07 Robert McKay Clyde Valley AC 29.27 Robert McFall Edinburgh Southern H 29.56

1977-8 William Stoddart Greenock Wellpark H 24.21 William Drysdale Law & District AAC 24.52 Tom O’Reilly Springburn H 25.04

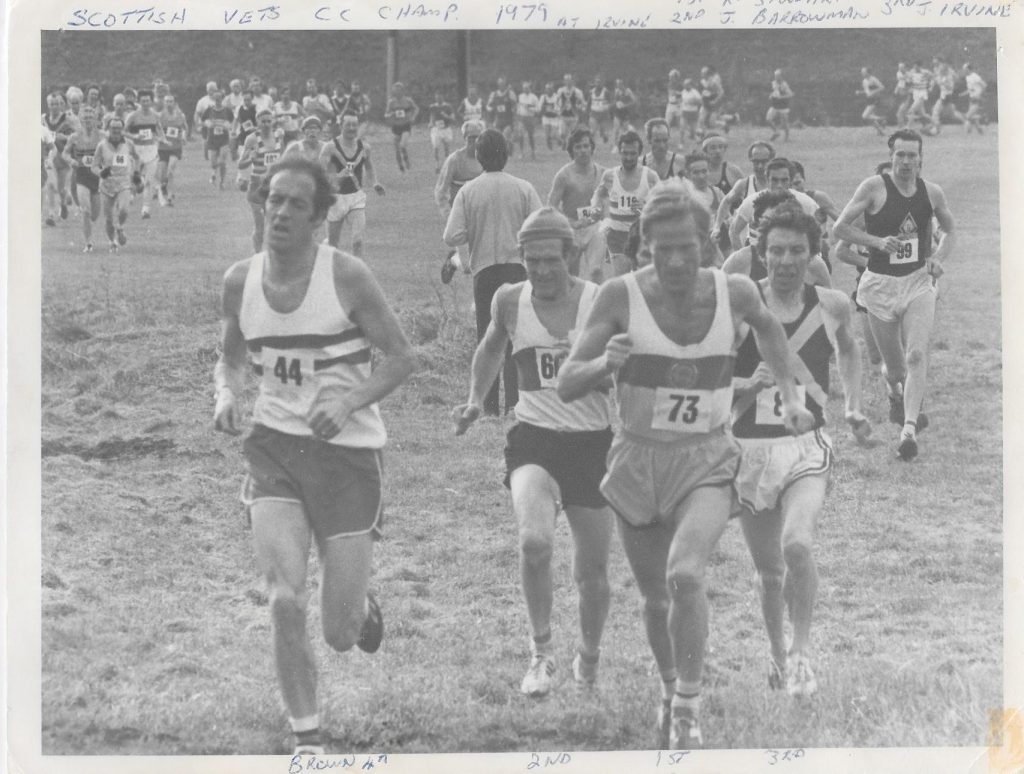

1978-9 William Stoddart Greenock Wellpark H 33.41 J Barrowman Garscube H 34.10 Jim Irvine Bellahouston H 34.19

1979-80 Donald Macgregor Fife AC 32.27 William Stoddart Greenock Wellpark H 33.29 Ron Prior Edinburgh AC 34.11

1980-1 Martin Craven Edinburgh Southern H 32.30 Andrew Brown Clyde Valley AC 33.19 Andrew Pender Falkirk Victoria H 33.39

1981-2 Andrew Brown Clyde Valley AC 32.29 Martin Craven Edinburgh Southern H 33.08 William Scally Shettleston H 33.22

1982-3 Donald Macgregor Fife AC 34.11 Martin Craven Edinburgh Southern H 34.14 Antony McCall Dumbarton AAC 34.23

1983-4 Richard Hodelet Greenock Glenpark H 30.47 J Lachan Stewart Spango Valley AC 30.59 William Scally Shettleston H 31.57

1984-5 Richard Hodelet Greenock Glenpark H 31.22 Allan Adams Dumbarton AAC 31.25 William Scally Shettleston H 31.30

1985-6 Brian Scobie Maryhill H 44.18 Allan Adams Dumbarton AAC 45.29 Kenneth Duncan Pitreavie AAC 46.31

1986-7 Brian Scobie Maryhill H 32.32 Brian Carty Shettleston H 33.00 David Fairweather Law & District AC 33.10

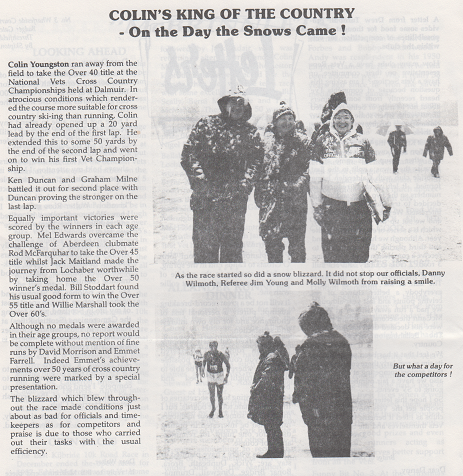

1987-8 Colin Youngson Aberdeen AAC 39.14 Archibald Duncan Pitreavie AAC 39.38 Graham Milne Aberdeen AAC 39.53

1988-9 Colin Youngson Aberdeen AAC 31.36 Charles McDougall Calderglen H 31.58 Peter Marshall Haddington ELP

32.29 1989-90 George Meredith Victoria Park AAC 35.48 Colin Youngson Aberdeen AAC 35.54 Brian Emmerson Teviotdale H 36.15

1990-1 Ian Elliot Teviotdale H 31.56 Colin Youngson Aberdeen AAC 32.36 John Kennedy Victoria Park AAC 32.45

1991-2 Ian Elliot Teviotdale H 35.23 Colin Youngson Aberdeen AAC 35.32 George Meredith Victoria Park AAC 36.30

M45

1984-5 Donald Macgregor Fife AC 31.50 John Linaker Pitreavie AAC 32.30 Ian Leggett Livingston AAC 34.03

1985-6 John Linaker Pitreavie AAC 47.09 Ian Leggett SVHC 49.00 Martin Craven Edinburgh Southern H 49.05

1986-7 John Linaker Pitreavie AAC 34.19 Martin Craven Edinburgh Southern H 34.35 J Moses Bellahouston H 35.17

1987-8 Mel Edwards Aberdeen AAC 40.55 Roderick MacFarquhar Aberdeen AAC 41.10 Richard Hodelet Greenock Glenpark H 41.57

1988-9 Allan Adams Dumbarton AAC 32.36 Roderick MacFarquhar Aberdeen AAC 33.12 Robert Young Clydesdale H 33.18

1989-90 Allan Adams Dumbarton AAC 37.46 Ben Pearce Aberdeen AAC 38.29 Robert Young Clydesdale H 38.53

1990-1 Allan Adams Dumbarton AAC 33.37 Bernard McMonagle Shettleston H 33.56 Robert Young Clydesdale H 34.11

1991-2 Allan Adams Dumbarton AAC 37.23 Colin Martin Dunbarton AAC 37.42 Robert Young Clydesdale H 37.58

M50

1971-2 Andrew Forbes Victoria Park AAC 34.35 Tommy Harrison Maryhill H 35.09 Walter Ross Garscube H 35.40

1972-3 Walter J Ross Garscube H 34.03 Gordon Porteous Maryhill H 34.10 Tommy Harrison Maryhill H 34.43

1973-4 George Martin Springburn H 31.12 R Clark Wallace Shettleston H 31.51 Jim Geddes Monklands H 33.14

1974-5 Tommy Harrison Maryhill H 33.41 R Clark Wallace Shettleston H 34.22 1975-6 Cyril O’Boyle Clydesdale H

1976-7 Ronnie Kane Victoria Park AAC 31.38 Cyril O’Boyle Clydesdale H 31.42 George Martin Springburn H 38.51

1977-8 William Marshall Clyde Valley AC 25.39 Ronnie Kane Victoria Park AAC 26.49 John Clark Clyde Valley AC 28.51

1978-9 Hugh Mitchell Shettleston H 35.04 William Marshall Clyde Valley AC 35.27 D Clelland SVHC 38.06

1979-80 William Marshall Clyde Valley AC 35.55 Tom Stevenson Greenock Wellpark H 36.37 Peter Milligan Clydesdale H 36.42

1980-1 William Marshall Clyde Valley AC 35.15 William McBrinn Clyde Valley AC 35.53 David Cleland SVHC 36.51

1981-2 William Stoddart Greenock Wellpark H 33.30 William McBrinn Clyde Valley AC 34.35 William Marshall Clyde Valley AC 35.30

1982-3 Alastair Wood Aberdeen AAC 37.11 William McBrinn Clyde Valley AC 37.18 Tom O’Reilly East Kilbride AAC 37.42

1983-4 William Stoddart Greenock Wellpark H 34.04 Tom O’Reilly Springburn H 34.56 William McBrinn Clyde Valley AC 35.08

1984-5 William Stoddart Greenock Wellpark H 33.30 William McBrinn Clyde Valley AC 34.32 James Milne Edinburgh AC 34.40

1985-6 William Stoddart Greenock Wellpark H 48.41 Pat Keenan Victoria Park AAC 50.38 Hugh Gibson Hamilton H 53.35

1986-7 Jim Irvine Bellahouston H 35.22 Hugh Gibson Hamilton H 37.39 D Fraser Bellahouston H 37.47

1987-8 Jack Maitland Lochaber AC 44.01 Jim Morrison Aberdeen AAC 44.24 Jim Irvine Bellahouston H 45.12

1988-9 Jack Maitland Lochaber AC 35.42 James Irvine Bellahouston H 35.53 Henry Muchamore Haddington ELP 37.01

1989-90 John Linaker Pitreavie AAC 39.17 Ian Leggett Livingston AC 39.34 George Armstrong Haddington ELP 41.57

1990-1 Donald Macgregor Fife AC 34.21 John Linaker Pitreavie AAC 34.55 Ian Leggett Livingston AC 36.40

1991-2 George Armstrong Haddington ELP 40.40 R Rotchford Springburn H 41.11 G Angus Dundee Hawkhill H 41.15

M55

1984-5 Tom Stevenson Greenock Wellpark H 36.22 Tom Kinsey Maryhill H 36.52 G Lawson Maryhill H 37.31

1985-6 William McBrinn Shettleston H 51.17 S McLean Bellahouston H 56.00 William Russell SVHC 57.47

1986-7 William Stoddart Greenock Glenpark H 35.53 William McBrinn Shettleston H 36.09 Hamish Scott Perth Strathtay H 38.00

1987-8 William Stoddart Greenock Glenpark H 43.36 Hugh Gibson Hamilton H 44.07 Sandy Robertson Troon Tortoises 47.08

1988-9 Hugh Gibson Hamilton H 36.25 William McBrinn Shettleston H 36.42 William Gauld Carnethy HRC 38.10

1989-90 Hugh Rankin JW Kilmarnock AC 39.18 Hugh Gibson Hamilton H 41.11 Owen Light Troon T 42.01

1990-1 William Gauld Carnethy HRC 37.53 Jim Irvine Bellahouston H 38.51 Steve McLean Bellahouston H 39.29

1991-2 Hugh Rankin JW Kilmarnock AC 38.36 Hugh Gibson Hamilton H 41.00 Bert McKay Ayr Seaforth AAC 42.42

M60

1971-2 J Emmet Farrell Maryhill H 42.18 Ron Smith SVHC 43.10 George Taylor Shettleston H 43.19

1972-3 Herbert Smith Maryhill H 36.57 J Emmet Farrell Maryhill H 37.21 George Taylor Shettleston H 39.02

1973-4 J Emmet Farrell Maryhill H 31.47 Gordon Porteous Maryhill H 33.14 Herbert Smith Maryhill H

1974-5 Gordon Porteous Maryhill H 35.14

1975-6 Gordon Porteous Maryhill H

1976-7 Gordon Porteous Maryhill H 34.55 Gavin Bell Bellahouston H 38.51 Tony Else Edinburgh AC 39.58

1977-8 Andrew Forbes Victoria Park AAC 29.14 Gordon Porteous Maryhill H 29.18 J Emmet Farrell Maryhill H 29.30

1978-9 J Emmet Farrell Maryhill H 41.32 James Youngson Aberdeen AAC 43.40 Walter Ross Garscube H 45.31

1979-80 Andrew Forbes Victoria Park AAC

1980-1 David Morrison Shettleston H 41.28 J Emmet Farrell Maryhill H 41.33 Gordon Porteous Maryhill H 41.40

1981-2 Gordon Porteous Maryhill H 41.26 David Morrison Shettleston H 41.39 Andrew Forbes Victoria Park AAC 42.37

1982-3 John Clark Clyde Valley AC 42.57 George Kynaston Aberdeen AAC 45.32 Gordon Porteous Maryhill H 45.32

1983-4 Thomas Kelly Shettleston H 42.36 Tommy Harrison Maryhill H 42.38 J Emmet Farrell Maryhill H 42.45

1984-5 John Clark Clyde Valley AC 40.50 J Kelly Falkirk Victoria H 42.28 Bill Adams SVHC 43.24

1985-6 Murray Scott Haddington ELP 62.44 John Clark SVHC 63.23 David Anderson Greenock Wellpark H 69.43

1986-7 William Temple Unattached 40.37 Ben Bickerton Shettleston H 41.34 Andrew McInnes Victoria Park AAC 42.28

1987-8 William Marshall Motherwell YMCA 47.55 W Templeton SVHC 50.12

1988-9 William Marshall Motherwell YMCA 37.04 William Gillespie Falkirk Victoria H 40.43 Anthony Hannah Moray RR 45.39

1989-90 William Marshall Motherwell YMCA 42.43 Hugh McGinlay Falkirk Victoria H 55.45

1990-1 William Marshall Motherwell YMCA 38.07 S Lawson Maryhill H 41.43 William Gillespie Falkirk Victoria H 42.55

1991-2 William Stoddart Greenock Wellpark H 40.21 S Lawson Maryhill H 46.23 John Elphinstone SVHC 48.16

M65

From 1981-84 the SCCU did not present medals for this category, but the SVHC may have. Unfortunately, there are no records available.

1984-5

1985-6

1986-7 Tommy Harrison Maryhill H 47.47 David Anderson Greenock Wellpark H 49.56

1987-88

1988-9 Tommy Harrison Maryhill H 49.05

1989-90 William Marshall Motherwell YMCA 42.43 Hugh McGinlay Falkirk Victoria H 55.45

1990-1 Hugh McGinlay Falkirk Victoria H 45.42 1991-2 William Gillespie Falkirk Victoria H 49.27 Robert Dempster Maryhill H 58.44

M70

1978-9 Roddy Devon Clyde Valley AAC 59.54

1979-80 J Emmet Farrell Maryhill H

1981-2 Herbert Smith Maryhill H 47.27

1982-3 J Emmet Farrell Maryhill H 46.07 1983-4

1984-5 Gordon Porteous Maryhill H 42.28 David Morrison Shettleston H 42.46

1985-6

1986-7 David Morrison Shettleston H 45.02

1987-8

1988-9

1989-90

1990-1 Tommy Harrison Maryhill H 56.50

1991-2 Tommy Harrison Maryhill H 83.00

M75

1984-5 J Emmet Farrell Maryhill H 45.14

1985-6 J Emmet Farrell Maryhill H 68.09

1986-7 J Emmet Farrell Maryhill H 51.43

1987-8

1988-9 David Morrison Shettleston H 46.46

1989-90

1990-1

1991-2 Gordon Porteous Maryhill H 55.42

FOR RESULTS FOR MEN AND WOMEN BETWEEN 1993-2020, CONSULT THE ARCHIVE OF THE SCOTTISH ROAD RUNNING AND CROSS COUNTRY COMMISSION.

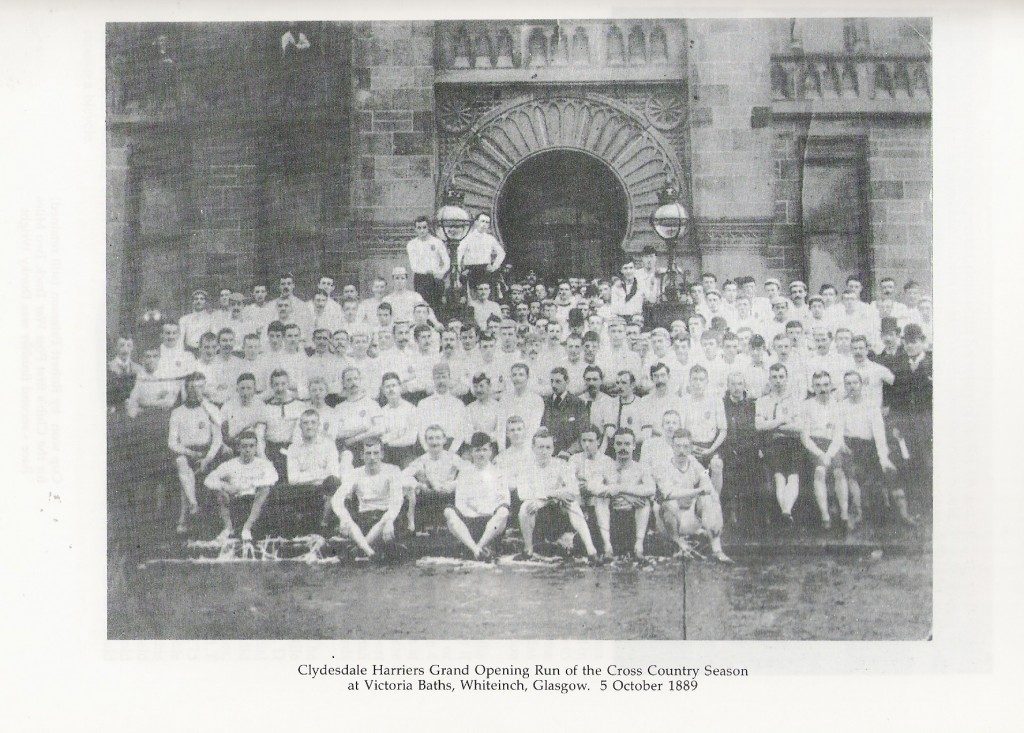

Edinburgh Harriers winning team in the inaugural Scottish Cross-Country Championship of 1886: 1 Tom Fraser, 2 David Colville Macmichael, 3 David Scott Duncan, 4 William Mabson Gabriel, 5 John William Lodowick Beck, 6 Peter Addison, 7 Robert Cochrane Buist, 8 John M. Bow

Edinburgh Harriers winning team in the inaugural Scottish Cross-Country Championship of 1886: 1 Tom Fraser, 2 David Colville Macmichael, 3 David Scott Duncan, 4 William Mabson Gabriel, 5 John William Lodowick Beck, 6 Peter Addison, 7 Robert Cochrane Buist, 8 John M. Bow