MCNAMARA’S BAND

Jack House, the well-known journalist and Glasgow historian was commissioned by the then Glasgow Citizen (now defunct) to write an article on “How harriers keep fit at Maryhill.” The club rigged out Jack with running gear. All they could get out of an old box were a rather long pair of shorts and shoes with a couple of holes in them but though he would not have won a prize as the best dressed harrier he joined Jimmy McNamara and George Barber in a short three miles jog. The pace was gentle and suited Jack who was no runner but much younger than his two companions who were ready to acquaint the journalist with their running prowess and back-ground. Though Jimmy did not cut such a fine figure as George he was that little bit faster so he piled on the pace and left the latter behind. So Jimmy had Jack all to himself and was able to provide his running background from A to Z.

On the Monday there was a big article in the Citizen with the headlines “McNamara’s Band”, all about Jimmy’s athletic history and associations. George had to be content with an honourable mention.

A STANDING OVATION FOR JIMMY

When Jimmy McNamara was 63 he had the temerity to run in the famous Drymen to Firhill 14 miles road race. Temerity because unlike nowadays it seemed almost unbelievable that anyone that vintage could even contemplate such a feat. On this particular occasion after the leading runners had been finished for some time the loudspeakers broadcast a special message “James McNamara that amazing veteran runner is now approaching the stadium.”

This was the highlight. The leading runners were secondary. The stadium was hushed, then expectancy changed to realisation as Jimmy appeared with his hand raised in salutation to accept the standing ovation he knew was obligatory and merited. Hew was a real character and forthright with it. At the Highland Games of those days, he was humorously critical of the officials parading in Highland Dress. Noting their white knees, he entitled them “Utility Highlanders.”

STILL THE BODY OF THE KIRK.

My own experience was somewhat different from Jimmy’s when as a veteran I turned out for old time sake in our clubs Nigel Barge four and a half miles road race some years ago. I was well back but unlike Jimmy managed to beat quite few runners much younger than myself. As I crossed the line an official said to me, “Are you still at it, Johnny?” There ain’t no justice, but at least I was still in the body of the Kirk but no ovation, standing or otherwise, was provided.

THE MOST UNKINDEST CUT OF ALL

I borrow the above quotation from Shakespeare’s play “Julius Caesar” to illustrate another anecdote concerning JimmyMcNamara. Another veteran runner arrived from Australia, named Charles Vance. Also over sixty, he was very fit and an extrovert. At every town he visited first stop was the leading newspaper offices where he profferred his credentials. He had a visiting card printed in the following terms: “Charles Vance, Australia’s leading veteran runner, now touring Scotland.” It was inevitable that Jimmy and he should meet up and compare notes. The former was also proud of his fitness relative to age and it got to the stage where birth certificates had to be produced to discover who had the advantage of seniority. It turned out that Vance was not only the better runner but that he was older. That was “The most unkindest cut of all.”

GEORGE ALSO GETS INTO THE ACT

Jimmy’s pal George Barber caused something of a furore on one occasion. It was a real “cause celebre”. Maryhill Harriers had commissioned a photographer to take a special commemmorative photograph of club runners. There was a large turn-out. Most of the runners were in running gear bar officials who wore suits, as did George, more in keeping with their more sedate mode of life. After all, they were all over sixty years of age. As the photographer, a true professional, was positioning his subjects, George held up his hand appealing for a short delay and adjourned to the clubhouse ostensibly as it seemed to visit the toilet. Some minutes elapsed before George stunned the waiting group by reappearing resplendent in full running gear. He received a standing ovation. It was well deserved. The audacity of someone of his vintage appearing in running gear was incredible.

CHANGING ATTITUDES

These incidents may appear facetious but they contained a quite serious attitude in those days. In Victorian times one was regarded as old at forty. Customs and tradition expected people to be their age and act staidly and with decorum. Perhaps I am not over-exaggerating by saying that when a man reached that age he was expected to grow a beard and moustache and spend most of his life in an armchair, then allowed out on a Sunday to play a little croquet and partake of cucumber sandwiches on the lawn. From a hirsute point of view, things appear to be a little different nowadays. Younger men tend to feature a beard or moustache to reveak desired maturity while seniors tend to remain clean-shaven, a gesture to off-set their unwanted age. But seriously, from a prely athletic point of view, the greates revolution has occurred in officialdom’s attitude to women.

WOMEN’S LIB IN ATHLETICS

Not so many years ago women were not allowed to run races longer than two hundred yards. Now they run ;long distances including the marathon and in the big people’s marathons accompany male athletes, a thing unheard of not so ;long ago. It is now recognised that while they may not quite have the speed of their male counterparts the stamina of the women compares more favourably.

TRIBUTE TO PIONEERS

In every activity in life pioneers deserve honour and tribute. It is easy to do something when it is fashionable and encouraged but a different story when it is frowned on. Lady runners owe their liberation to people like Dale Greig from Paisley who was one of the first to demonstrate that it was not abnormal for women to run long distances. Though versatile enough to win Scottish Titles and International recognition her chief love was running long distances but also the audacity to run unofficially in the London-Brighton fifty miles classic.

To beat three and a half hours in the tough hilly Isle of Wight Marathon may seem normal nowadays against the professional approach of the moderns but equally does Roger Bannister’s sub four minute mile. But the pioneers point the way for those who follow in their footsteps.

IMPORTANCE OF PSYCHOLOGY IN SPORT

Reference to Bannister leads nicely on to the importance of the mind in athletic contest. When Roger Bannister broke the four minute mile barrier a whole procession of runners queued up to demonstrate it wasn’t so difficult. From people like Landy of Australia, Jazy of France, Herb Elliott, Peter Snell and John Walker of New Zealand, our own Derek Ibbotson to the modern greats like Coe, Ovett, Cram, Aouita and many others. Modern philosophers recognise the close dependence of body and mind with their common use of the terms body-mind or mind-body to emphasise the difficulty in separating the terms.

OTHER EXAMPLES FROM THE PAST TO THE PRESENT

People have always recognised this to some extent and none more so than those indulging in athletic pursuits. Many years ago, three famous personalities of the twenties proved how important the mind is in physical achievement. Film star Douglas Fairbanks Snr, Charlie Chaplin and Olympic champion sprinter Charlie Paddock were great friends and buddies and often indulged in athletic hirseplay. Their initial attempts to clear a gap, managed it and immediately the other two duplicated his feat. It could be done, it would be done, it was done. All that was needed was confidence.

THE TIRED SWIMMER WHO BROKE A RECORD

It was well-known that one can have instant recall to something that happened years ago, yet cannot remember clearly recent events. Many years ago when my sport was swimming there was a fine Scottish swimmer from Motherwell called Harry Cunningham. He was tall and loose-limbed and in those days unemployment was worse than it is today. Jobs were at a premium and poverty was rife. It was the time of the dreaded means test.

Just short of the height to join the Scottish Police Force, he travelled down to Oldham for an interview for entrance to a combined fireman and police job where standards were less stringent. After his interview he travelled back to Motherwell pretty tired and travel weary to find that he had been billed to attack the Scottish 150 yards, six lengths of the pool…

After a cup of tea, a pie and a short rest he made his way to the gala inb a frame of mind less than euphoric. His friend spoke to him like a Dutch uncle. “Harry, you’ve nothing to lose. Just go out and enjoy yourself and swim a brisk hundred yards as best you can.” His eperience down south was broadcast to spectators and so with the pressure off he went out uninhibited and relaxed. He set off as if he was swimming the hundred yards, felt good, kept going and beat the record.

GO ON, I’M DONE

Many years ago I experienced an example of mind over matter. Running in a cross-coutry race, two of us were in the lead. Suddenly I felt very weary and decided that I could not sustain the pace much longer and would have to let my opponent get away. Being very competitive I tried to hang on for just one stretch of field. Suddenly my rival shouted, “go on, I’m done!” I oberued with alacrity. I could never fathom how near exhaustion was immdiately transformed into a burst of explosive energy. Logic suggests that there must be limits to the assistance provided by the mind to the body. But psychology is a comparatively new and inexact science and I believe there is more to be learned in that area.

A good programme of racing kept the sport going during the war years but being unofficial they did not reach the interest and prestige as official championships. Road races did not provide the numbers as they do today. For example when I won the Nigel Barge Memorial Race over four and three quarter miles at Maryhill in 1944 there were only about 25 starters and my time was just over 24 minutes. Nowadays there are fields of over 200 runners and the time is at least two minutes faster.

A YELLOW CARD FROM JOHNNY LINDSAY

Many of the athletic galas in those days featured road races from, say, ten to fourteen miles and most of the participants formed a sort of fellowship, a brotherhood of the road, practically a family affair. At the start it was often like a pack run and it was considered bad form to race from the gun. In some of these races my old friend Harry Howard of Shettleston and myself were the main contenders and there were cries of “Lay off the pace” if either of us tried to inject pace from the gun. It was only when the rest of the field could not sustain the modest pace that we eventually left the pack behind and the real racing started. On one occasion Harry and I were jockeying for position for a breakaway like greyhounds on the leash when we accidentally bumped into each other. No one was hurt but Harry being lighter got the worst of it at which Johnny Lindsay of Bellahouston shouted “That’s enough of that!” A few seconds later we again collided in our eagerness to get ahead of the pack and again Harry got slightly the worst of it. There was no harm done and no resentment by either of us, but Johnny shouted out, “No that’s the last time I’m going to warn you.” We were both grateful that it was only a yellow card and nt a red card that we recived. We eventually got away with aspersions still ringing in our ears. But now the racing was for real.

With that mixture of frivolity and seriousness it was predictable that there were few record-breaking performances.

When athletics re-started on an official basis in 1946 pre-war athletes had lost six years and it was inevitable that their best years were on the wane. Speaking for myself, although I continued to do very well in a local and national level I had lost the basic snap and speed with which I had hoped to emulate Jim Flockhart as a possible winner of the International Cros-Country title. Still Jim and I continued to retain consistency and gain many jerseys. Having won only three pre-war I managed to gain another seven post-war, the last at 43 years of age, making a total of 10 jerseys, never out of the first four in the National. With the loss of six probable jerseys that could have made 16 appearances for Scotland, and 17 for Jim nearly a record, though I understand that Van De Wattyne of Belgium might have earned more.

EMERGENCE OF RAPHAEL PUJAZON

The first post-war cross-country international in 1946 was held at Ayr race-course but was most disappointing for Scotland. Placing fifth out of six in the team race it was left to veterans like Jim Flockhart and myself to get modest positions of 15th and 25th. After a great race, Pujazon of France beat Van De Wattyne of Belgium. Those were the days when three days a week was the training norm for athletes. So when one of Pujazon’s entourage volunteered the amazing statement, “Raphael s’ entraine tous les jours” (Raphael trains every day) his audience was thunderstruck. In those days it was normal procedure to nurse and cosset the physique. Now it is recognised that the body is a more elastic medium than was ever imagined.

FIRST POST-WAR TRACK CHAMPIONSHIPS

Winning the ten miles track championship at Helenvale Park was some compensation for a moderate run in the international cross-country event and then added the six miles and three miles titles showed that even at 37 I still retained useful form. The times were moderate. For example 54:38 in the ten miles but I had half a lap to spare from my old rival Alex McLean of Bellahouston and as the six miles and three miles were on consecutive days I just did enough to win especially in the first race where energy had to e husbanded for the morrow’s task.

After winning the 19 Miles Track in 1950

After winning the 19 Miles Track in 1950

THE RACE OF THE CENTURY?

There must have been many races that deserved that accolade but I was privileged to watch one that for drama and excitement came into that category, the 1946 three miles AAA title featuring Sydney Wooderson of England and Slykhuis of Holland. Lap after lap they shadowed each other with Wooderson leading at the bell. On the back straight, the Dutchman tore into the lead but the tiny dynamic Blackheath runner got on level terms in the straight and in a blistering finish breasted the tape five yards ahead. Hats went up in the air and when it was announced that both men had beaten the all-comers record of Maeki of Finland, the applause lasted for several minutes. Wooderson’s time was 13:53, exceptional time over 40 years ago. Many faster races have taken place and will inevitably do so in future but there will never be a better ne.

THE VETERAN PROVIDES AN ENCORE.

A month later at 32 years of age Wooderson ran his last big international race and it was amost a repeat of his earlier triumph in the AAA three miles. This time it was over the slightly longer distance of 5000 metres and the field was even stronger with the addition of Heino of Finland, Pujazon of France, Peiff of Belgium as well as Slykhuis. To be fair the great Finn had won the 10000 metres the day before and this stamina sapping event must inevitably have taken its toll. Nevertheless it again developed into a duel between the Britisher and the Dutchman. This time however it was Wooderson who shadowed Slykhuis, biding his time and making his effort two hundred yards from home. The latter could not cope with his dynamic finish and the margin of victory was a good 25 yards. It was a wonderful climax to the veteran’s career when it is realised he was giving away some years to his opponent and had survived rheumatic trouble contracted during military service. To win the European championship was some compensation for his Olympic disappointment of 1936 when injury spoiled his chances of a confrontation with the great Jack Lovelock. Wooderson’s running style and his private demeanour were in complete contrast. He later returned to cross-country which he enjoyed recreationally and even managed to win the English National in 1948 and finished a good twelfth in the International at Reading after standing all the way in the tube to the venue. I remember having a word with him at the after-race banquet and was taken with his quiet almost difficent manner. He was one of the last breed of great amateurs. Running was his hobby. His success incidental. Four years later Jack Holden another Olympic athlete was himself to win European titles at 43 years of age, another example ofcombined talent and grit.

PERTH TO DUNDEE RECORD

After my triple success at ten, six and three miles in the resumption of official post-war athletics, my enthusiasm and appetite for racing returned. The times were, as I said, moderate but the races run without pressure and with my tendency to be lazy and just do what was required to win. I was reasonably happy with my form at the near veteran age of 37. With my fading sharpness over the shorter stretches I felt inclined to experiment over longer distances and decided to run in the prestigious Perth to Dundee 22 miles race which had attracted runners of the stature of Dunky Wright , Donald Robertson and Tom Richards, unlike myself all marathon specialists. Club-mate Dunkky still in splendid shape for a veteran of 49 had won quite a number of races against much younger opponents during the war period and was keen to add a third victory to his previous two successes in his final race.

He was definitely the one to beat. Despite his years his uncanny judgment of pace and years of experience to some extent compensated for by the passage of time. Even at 37 years of age I was something of a stripling against his 49 years. We set off on a lovely September day with ideal running conditions and right away it was obvious that it was to be a two man race. I followed Dunky’s steady brisk pace for two reasons.

Firstly I recognised his uncanny judgment of pace and secondly I was a bit inhibited, uncertain how I would react to a distance just four miles under the full marathon distance. Mile after mile I shadowed the master feeling comfortable but lacking the confidence to take the initiative. But at Invergowrie about three miles from home I decided to make my move, went relentlessly ahead to win in the record time of 2 hours 4 minutes 43 seconds. 1 minute 3 seconds inside the old record. How was I to know that Donald Robertson was to regain his record a year from then!

Someone worked out my time at 5 minutes 43 seconds per mile, which if sustained for the other four miles would put me in the 2 hours 30 minutes marathon bracket. I was never to reach that target but on the day I was so strong and comfortable that I felt such a time was within my compass. Up to that time only Son of Japan had broken the two and a half hours barrier. On three to four days a week training I felt I had potential but quite soon with the advent of Jim Peters with his rigorous training schedule and pillar-to-post tactics, such times were out of date. It was the two hours twenty minutes barrier which was to be beaten uncompromomisingly and often.

MARYHILL’S RELAY SUCCESSES

A month later the cross-country season opened with the annual “McAndrew” trophy race at Whiteinch over approximately three miles per man. Running the anchor leg I had the uncomfortable experience of being chased by Victoria Park’s Andy Forbes only 9 seconds behind. Running my usual pillar-to-post race, I was mightily relieved to breast the tape 14 seconds ahead covering the distance in sixteen minutes to Andy’s sixteen minutes and five seconds.

Later we won the KIngsway Relay over a flat fast course this time beating old rivals Bellahouston. Victoria Park were relegated to third place but Andy Forbes pipped me by one second for the fastest time award, 14:22 to 14:23, 3rd and 4th equal were J Clark, Maryhill and C McLellan, Shettleston, 14:28 with well-known names of the past Alec McLean, Bellahouston, 14:31 and Charlie Robertson, Dundee Thistle 14:32.

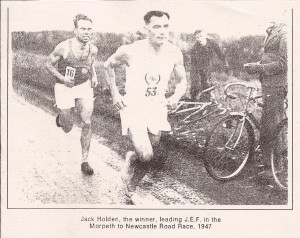

HOLDEN WINS MORPETH DUEL WITH FARRELL

That was the headline after the annual Morpeth Road Race. Although beaten I was pleased to have given the famous Tipton Harrier such a hard race. We were locked together most of the way and on several occasions I took the lead, but finally Jack Holden prevailed by almost 200 yards; over 1 minute outside the record at that time. After the race he looked tired and drawn and complained of a septic heel. I often wondered if his feet were his weak point, he certainly had no others. A year later he had to drop out of the Olympic marathon at which he was one of the favourites ostensibly with blisters. Perhaps tender feet were his Achilles heel. Maryhill had the consolation of winning the team race, our trio finishing Farrell (2), Porteous (8) and Martin (13).

FORBES TIP-TOES THROUGH THE SNOW.

onThe winter of 1947 was one of the coldest m record and those of us who suffered that of 1987, 40 years later, must heave a sigh of fellow feeling. The venue of the National cross-country, Lanark race-course, was snow-bound and the runners had to negotiate eight laps of the race course. The snow was too deep and dangerous to go into the open country. It was a gruelling and somewhat boring experience almost like an extended track race and as the large field of runners levelled out a path in the deep snow it was difficult to gain a place unless by stepping out and that of course used up quite a bit of energy.

Victoria Park’s Andy Forbes elegant strides took him nicely over the soft going and he finished a good hundred yards in front of Alex McGregor of Bellahouston. I was happy to finish third a further fifty yards in the rear. A surprise and disappointment was Jim Flockhart’s poor performance though it was later learned that he had sustained a foot injury and had to run in plimsoles, unsuitable fr the extreme and slippery underfoot conditions. Jim was well back in 40th place.

FLOCKHART’S GREATEST RACE

The selectors were in a quandary but mindful of Flockhart’s class and competitive zeal selected him to the exclusion of Lamont of Victoria Park who was 8th despite the fact that the former at 38 was approaching the veteran class. It was a difficult decision and there was some muted criticism, but Flockhart had the last word by running the race of his life at the St Cloud race-course in Paris, finishing in 7th place only 71 seconds behind the winner, Raphael Pujazon of France who retained his International title. Scotland’s counting six finished as follows:-

Flockhart 7th; Farrell 19th; R Reid 20th; Forbes 26th; Sinclair 28th and A McGregor 37th.

I rate this run by Flockhart as one of his greatest. Perhaps as good as his win in Brussels in 1937, especially considering ten years had elapsed and in view of the strain and responsibility he was labouring under. His lap positions 20th, 14th, 8th and 7th reveal the progressive and well-judged pace of this run.

AH, MONSIEUR PICKWICK

If our team had little reason to remember that race there were many other amusing and unusual incidents worthy of recall. Bob Lindsay of Paisley followed the fortunes of Scottish cross-country teams since 1912 with just the odd exception. As a bachelor he travelled everywhere with them making it his holiday much like a loyal football supporter. With his black coat and bowler he was a kenspeckle figure and the French party with Gallic whimsicality dubbed him “Monsieur Pickwick”, recognising his Dickensian appearance. Now why didn’t we think of that?

There were other amusing incidents. Some of the lads adjourned to a cafe for light refreshments and one of our party started to play a few tunes on the piano. We were asked to pay extra for entertainment provided despite the fact that it was one of outr chaps who was providing the entertainment! Even in our hotel after the race,Frank Sinclair and I went to turn on a hot bath in our room to try and get rid of some fatigue and stifness but we had to request a key to turn on the tap and were asked to pay extra for that service.

LAST IN THE QUEUE

Each nation was allocated a Public Relations Attendant to look aftre our comfort, travel arrangements and act as interpreter. Ours was a Monsieur Demande, very French, very patriotic and very competent. His first duity was to warn us about street peddlers asking for “Zee English Point”. Post-war conditions had upset the exchange rate. Sterling was most advantageous to France but not in the black market and certainly British tourists were offered more francs per pound than were legally allowed. At the end of our stay our party said our good-byes to Mr Demande and his charming wife.

Thanking him for his services I sought to air my French and pay the latter a compliment. “Votre femme est si charmante,” I said. With a typical Gallic chivalry he kissed his wife. At that everyone queued up to kiss mdaame and I was last in the queue.

THE LATE LATE SHOW

Because of the gruelling long winter the cross-country season had to be extended into April. Maryhiull’s club championshipusually held in February took place on 12th April and the weather had dramatically changed to almost summer-like conditions. Cross-country racing is not ideal in such heat and in addition the start of plouighing made it even more rigorous. Unhappy on such going I was relieved to win in circumstances totally opposed to those normally endured.

A TITLE AT LAST FOR ALEX McLEAN

“Always the bridesmaid and never the bride” may not be the best metaphor to describe a male athlete but it certainly described Alec McLean’s futile efforts to win a title over field or on track. But at last on Helenvale’s trim fast narrow track he was at last successful, winning the ten miles title in convincing style. Though the title holder and victim I could not grudge Alex his success with a nice display of front running. I also lost my other titles but this was by default, George Craig of Shettleston taking the six miles and the ever improving Andy Forbes of Victoria Park adding the three miles title to his earlier cross-country win. My marathon debut was a modest one.

Donald Robertson retained his Scottish title in 2:37:49. In the runner-up position I finished in 2 hours 42 minutes 53 seconds losing considerable distance over the last three or four miles where Donald’s experience and stamina proved the deciding factor.

JACK HOLDEN WINS AAA MARATHON

On a hot sultry August day and over amn arduous course Jack Holden outclassed his rivals in the AAA Marathon at Loughborough. It was veterans day with a vengeance as the result showed. 1. J Holden (Tipton) 2:33:20.2; 2. T Richards (South London) 2:35; 3. D McN Roberston (Maryhill) 2:37:54; 4. JE Farrell (Maryhill) 2:39:46. Holden and Roberston had reached forty years of age while Richards and I were respectively 37 and 38 years of age. Of the 64 starters half retired because of the heavy sultry conditions so that the times were worth at least five or six minutes better. Turkish champions M Kaplan who had recently set a Turkish record of around 2 hours 34 minutes was rumoured to be attempting a five minute per mile schedule which was unbelievable in those days but he flattered to deceive and finished 12th in 2 hours 55 minutes.

THE ECCENTRIC MR GRIFFITHS

It has been said that goal-keepres and marathon runners are mad. An exaggeration would be the immediate response but it is fair to say that there may be some eccentricity in the ranks. For example Les Griffiths of Reading, another enthusiastic veteran was a real character who regarded himself as a mentor-coach but not so much on the side-lines as while running in actual races. At Loughborough he had a cyclist in attendace with a tray of bottles and phials all marked and which he requested at intervals. I am not suggesting that anything illegal was involved as Les was an honourable man and everything was open and above board but he was an extrovert. Perhaps glucose, salt tablets, smelling salts and the like were involved. Nevertheless it seemed strange that this attendant was allowed as in those days drinks and water were permitted only at specific and well-spread out intervals unlike today when liquids are offered more constantly. At five miles Griffiths and I, running together, were one minute behind the leaders who included Holden, Richards, Roberts, Ballard, Henning and Humphries. The Turk who was running in bursts began to fade. Griffiths said to me “we’re running at six minutes to the mile” and suggested caution in the heat-wave conditions, saying most of the leaders would come back. He was right but the constant talking and admonition tended to be irritating and I was glad to move ahead with his voise still ringing in my ears and then his attention was turned on the nxt runner who was now at his elbow. Compared with today the times were moderate but those were hard-working amateurs running in spare time and without sponsorship. As a matter of fact Donald Robertson won his first AAA marathon title running in 1/11 shoes out of Woolworths. Time marches on.

AN OLYMPIC POSSIBLE

By virtue of my forward running I was promoted to those select few regarded as Olympic possibles. There was of course no sponsorship but we received occasional food parcels from abroad as post -war food rationing was the order of the day.

FARRELL’S JOURNEY NOT NECESSARY

From triumph to disaster in one year was my fate in the Perth to Dundee 22 miles road race. It developed into a contest between two members of the Robertson clan, Donald McNab abd newcomer Charlie, cyclist turned runner, both ran brilliantly, Donald winning in 2:33:25 beating my record by 1 min 18 sec and two and a half minutes faster than his 1942 time. Charlie’s magnificent debut of 2:05:17 was only 34 seconds outside the old record. I finished fourth in the unbelievably poor time of 2:15:20.

During the war period, the Government issued a directive advising people not o travel unless it was absolutely necessary and after the race a Sunday paper had a jest at my expense with the caption mentioned above that “Farrell’s journey was not necessary.” In other words I might as well have stayed at home. But little did they realise the upsets that I had experienced before the race. Not allowed time off from my job. I worked till 12 noon on Saturdays. Maryhill colleague George Barbner hired a small car and another runner drove me up to Perth. More used to heavy lorries the small light car proved somewhat difficult to handle and we were almost involved in an accident. When we eventually arrived at the start, changing hurriedly after partaking only a sandwich and a cup of tea on the way, it was only natural that my performance matched my depletion of nervous energy. Journalists sometimes assess things on a purely objective basis not realising subjective circumstances. Later I may touch on another similar experience when I was a veteran runner in the Glasgow Marathon.

However I must admit I invariably got an excellent press in those days. I appeared to be good copy for the sports writers as, win or lose, I was a trier and very competitive. Especially in relay races I poured myself into my running and though not always did I manage to catch a runner in front of me no one ever passed me from behind.

COME-BACK PERFORMANCE

A week, they say, can be a long time in politics. It can be equally so in athletics. Just seven days after the Perth to Dundee debacle I again faced my friend and rival Donald Robertson over the slightly favourable distance of seventeen miles. It was two-man race and I shadowed Donald the whole way. The pace was comfortable but even the distance of seventeen miles was inhibiting. At half-distance we were two minutes inside Dunky Wright’s old record but the pace dropped and by Thornliebank about two miles from home, we were just nineteen seconds inside the record. I felt comfortable and held my fire until about a quarter of a mile from home, sprinted to the tape, nine seconds or about 50 yards in front for a new course record of 1 hour 36 mins 2 secs, but only three seconds inside.

The time meant nothing. I was determined to win the race, running not so much against Donald but mindful of the unfair criticism levelled against me the week before by armchair critics who had probably never even run for a bus.

MORE UPS AND DOWNS

1948 being an Olympic year I decided to have another try at the Morpeth to Newcastle road race on New Year’s Day. But unlike the previous year’s race pushed Holden to the limit, this time I finished a poor fourth. Local favourite Bert Hemsley of Gosforth made a splendid come-back to win in 1 hour 13 minutes 15 3/5th seconds. A race he last won eleven years previously in 1937. Charlie Robertson made him go all the way and ot was only Hemsley’s experience and strength over the last mile that ensured him victory. The former’s potential was shown by the times of the first four.

1. B Hemsley (Gosforth) 1:13:15 3/5th; 2. CD Robertson (Dundee Thistle) 1:13:58; 3. W McMinnis (Sutton) 1:14:03; 4. JE Farrell (Maryhill) 1:14:45.

Nothing daunted I again retained the Maryhill club championship over our seven miles country trail and again looked forward confidently to the National Cross-Country Championship at Ayr Race Course. Although nearly 39 years of age and slightly slower I felt capable of again making Scotland’s team as the nine miles trail was something I revelled in and I still had a good combination of speed and stamina. There was no way I visualised winning. My aim was to make the first six and ensure selection.

AYR – MY LUCKY COURSE

With runners of the cal;ibre of Alex McLean, the ten miles track champion, Frank Sinclair, the one mile champion, Charlie Robertson and the splendid Shettleston trio of Jim Flockhart, Jim Ross and George Craig even that seemed a daunting task. Running steadily and within myself I eventually threaded into about sixth place and felt that was enough. Moving into fourth place my intention was if possible to retain that comfortable position. By then I was perhaps just twenty five yards behind the leaders Alex McLean, George Craig and Frank Sinclair.

They were obviously playing cat and mouse with each oither. Before I knew it I was on their tail. Suddenly I felt good and decided to inject pace. Whether I took them by surprise I cannot say but I opened up a gap of about thirty yards. On the downhill stretch to the open country I increased my lead and then there was just a fence to negotiate before the long (asit seemed) six hundred yards to the tape. As I got over that last hurdle I had a quick look back and saw to my consternation that the chasing runner was Frank Sinclair, faster than me and seemingly not too far behind. But I was over the fence and away.

He still had to reach and get over it and that takes time for a runner after a hard nine miles. I did not panic but kept something in reserve till some two hundred yards to go and then gave it all I had. The winning margin was some sixty yards. The first six places were as follows:-

1. JE Farrell (Maryhill) 51:27; 2. F Sinclair (Greenock W) 51:40; 3. Geo Craig (Shettleston) 51:31; 4. A McLean (Bellahouston) 51:57; 5. CD (Dundee Thistle. Robertson 52:33; 6. JC Flockhart (Shettleston) 52:49

Facetiously I said that I stole the race. Perhaps that wasn’t strictly true as if runners have over a mile to catch a leading runner and fail, that tells its own tale.

A DOUBLE JUBILEE WIN

After winning and leading my club to victory in their Golden Jubilee year it was nice to win the individual title again ten years on in their diamond jubilee year, especially as I was now a veteran of nearly 39 years. Despite running a poorish race in the Morpeth road race three months earlier it is possible the extra training distance provided that extra stamina which proved crucial over the later stages of the nine miles national course.

Receiving the Trophy from wife Jean with son Jack looking on, 1948

Receiving the Trophy from wife Jean with son Jack looking on, 1948

BELGIUM AND FRANCE OVERWHELM HOME COUNTRIES

In the International at Reading, Belgium and France fought out a great battle, the former winning by a single point, 46 points to 47. Even Sydney Wooderson the reigning English cross-country champion finished only a moderate 14th. Though when it is realised that he was not essentially a cross-country runner it wasn’t a bad performance, better than my modest 29th in the middle of the field. Bobby Reid in 12th place had his best run in a Scottish jersey. Charlie Robertson 20th, Alkex McLean 25th, myself 29th, Jim Flockhart 37th and George Craig 38th completed our counting six. Alex McLean had a good season retaining the 10 miles track and winning the 6 miles in a championship best. A fine versatile runner the cross-country title was the one that eluded him.

CHARLIE ROBERTSON’S GREAT BID IN OLYMPIC TRIAL

Jack Holden won the marathon Olympic trial after a very hard race from Tom Richards with Stan Jones of Polytechnic 3rd, but a hero of the race was Charlie Robertson who led narrowly at twenty miles but was forced to retire at 23 miles when his legs gave out. I had to retire at twenty miles. At five miles when running easily a muscle in my right leg tightened up. For fifteen miles I trailed the leg and tried to nurse it but at twenty miles I had to slow down to a walk. For the first time in my career I failed to finish the course and it was especially disappointing since it was such an important race.

Unlike last year the course was fast and conditions good yet the times were appreciably slower. Some felt that the course was longer. But this was not checked. Holden admitted that Robertson had him worried for a time and he looked tired and jaded. In the light of his later retiral in the Olympic event when he had to retire ostensibly because of blistered feet, could he have been a bit over-trained? Certainly Holden usually had the beating of Richards, but the latter ran the race of his life to finish a mere 16 seconds behind the winner Cabrera of Argentina and was gaining on him at the finish. Holden wasn’t finished as he was to prove gloriously two years hence in 1950.

The year 1948 may have been a forgettable one for me running-wise except for my win in the National Cross-Country Championship, but it was a unique year in another respect and that was meeting and staying with two amazing characters in the world of athletics.

ARTHUR NEWTON AND PERCY CERUTTY

They were two of the greatest personalities in sport I had the good fortune to meet. Absolutely opposite in nature and temperament, Newton an introvert, a typical English gentleman in the best meaning of the word; Cerutty the dynamic extrovert but both equally enthusiastic as regards athletics. Newton did not approve of Cerutty’sbluf manner, his strong and colourful Australian language and his rather bohemian nature, for example in his practice of walking about the house clad only in shorts. Even in casual attire the former’s wearing of the tie was mandatory. Yet their respect and even affection was mutual. Once when we returned to his house in Ruislip Manor, Newton put his fingers to his lips whispering, “Quiet please, Cerutty is sleeping.”

Cerutty took some of hus for a spin in the London suburbs. This was before the association with the great Herb Elliott and he frightened the life out of some of the ladies quietly shopping as he demonstrated his style of dynamic running. No wonder, a white-haired man running as if his life depended on it was a far cry from coffee and biscuits and the quiet chatter of suburbia. I have emphasised the deep contrast between Cerutty and Newton but there were similarities too, namely that they were attracted to the sport fairly late in life. Why such a scholarly gentleman as Newton had been attracted to running in the first place seemd a mystery. Apparently he used it primarily to publicise a farmer’s cause as he was a cotton and tobacco farmer at the time. To win a widely advertised race would focus attention on his particular cause and possibly provide remedial legislation. His two most populat booklets “Races and Training” and “Commonsense Athletics” were little athletics classics. In modern terms they may seem a little out-dated but the more one reads and studies them, the more one realises, to copy a title, it is basic commonsense. He advocated stamina as the first and essential ingredient of athletic success and certainly he was no mere theorist as he himself won many long distance races not just over the standard marathon of 26 miles 385 yards but also the Comrades Marathon over 54 miles in South Africa and the gruelling 24 hours run.

He set records in his time, now mostly all surpassed but he was the pioneer and remember he had to overcome a weak heart condition and was over forty years old before he took up the sport of distance running seriously and even then had to oversome a heart-shock condition.

On the other hand Cerutty, influenced by Newton, took up running on his own admission quite late in life for health reasons. Almost a semi-invalid for some years he decided to try and regain health and fitness by living a natural life and that meant activity, exercise and a healthy diet and what better activity than running. He elevated it to the level of philosophy, a mixture of stoicism, spartanism and dynamic effort. To run with gusto over natural surroundings, paths, scrub, sandhills rather than on the track. A running evangelist as opposed to coaches like Stampfl and Greschler. The former a devotee of the stop-watch and interval running, fast and slow in turn, the latter adding to that extensive testing of the body under laboratory conditions, a scientific concept much used and advocated in our modern professional trend. Perhaps one could embrace the two in a holistic approach but because the primitive joy of running for its own sake must for me take precedence I have more sympathy with the Cerutty philosophy. The track and laboratory are poor substitutes for the poetry of nature, the surge over path and field and the immense freedom of sky and distant horizons. Both Cerutty and Newton were mature men when they took up running, the former interested in philosophy and the poetry of Walt Whitman and the works of Emerson and Thoreau. The latter had a library of books and enjoyed classical music. Yet despite their culture they had a naive Peter Pan attitude to running, perhaps like other veterans who have taken up the sport late in life it represents to them a new dimension.

To us it became a “way of life” but to them iot became a demanding imperative – almost a road to paradise.

I met Cerutty only on one occasion, his name pronounced as he always insisted as in sincerity. But Imet and enjoyed Newton’s company and hospitality many times so I can write much more about him.

His house was a mecca for all athletes. His hospitality and encouragement was immense. The door hardly opened when one knocked to hear the inevitable welcome, “tea or coffee?” Some of us were amazed to find that he had up his own bed to Cerutty and was sleeping in a small makeshift one. He still ran when he retired for fitness but very early in the morning for two reasons. First because in his racing days in South Africa he had to do so before the heat of the day and it became a habit, and secondly because of his failing eye-sight. At that toi us unearthly hour there was less traffic about.

It was indeed a privilege to hace known this shy, yet enthusiastic and loveable man of whom it could be said as GK Chesterton said of Charles Dickens, “you could walk into his heart without knocking.” In the columns of ‘The Scots Athlete’ edited and published by my friend Walter J Ross there is a short tribute to Arthur Newton from my pen which attempts to sum up the characteristics and personality of the man which made him so much loved and respected.

ROOM AT THE INN

It has ever been thus. With few exceptions there has been no room at the inn. Arthur Newton’s case was that there was always room at the inn. His home was an open house for all manner of athletes and sportsmen. They droped in locally, often in running strip for a chat or advice.

He had correspondents all round the world. Hosts made pilgrimage to this shy reserved gentleman, who had their interest and that of the sport so much at heart. I well remember occasions when his living room was crammed with visitors, discussing all aspects of athletics, sometimes even philosophy, poetry and music. Mr Newton, pipe in the mouth, loved to listen, occasionally making a telling point or opening up a vista of speculation. Champions were proud to meet him. Tyros and novices sought him out.

Paradoxically he lived alone but was never lonely. As a bachelor he had a legion of “athletic sons.” He was a professional runner and “Mr Amateur” himself. All who knew him formed part of a brotherhood of sportsmen. Now alas at this time a brotherhood of sorrow. Although in his day a distance runner of tenacity and world class, I cannot dwell on the athlete. Newton the man captured my imagination too much. The greatest tribute would be a living memorial that we who have experienced so much, his kindness, his sportsmanship, his manliness, should try to some extent, to be his disciples for the things for which he stood. For truly he cast his bread on the waters.

MUD BATH AT AYR RACE-COURSE

After an Olympic Games a feeling of anti-climax normally prevails, but cross-country enthusiasts usually manage to throw off any lingering lethargy or relaxation. Hibernation is not for them and the call of path and open country and its ensuing sense of freedom is a responsive one. I still felt that despite being nearly forty and losing pace I could still win another Scottish Cross-Country jersey. The nine miles prevailing in those days was still a severe stamina test over race-course turf and having again won my club championship title over 7 miles I was in a buoyant mood. Ayr race-course was my favourite cross-country ground.

Regarded as a fairly light fast course I revelled in it. A speed merchant’s dream. I had won my two championships over its verdant turf despite the general view that a heavy course would suit me more. This was not so but third time was unlucky. Weather conditions were atrocious and after the race many runners were distressed and some were bleeding profusely from barbed-wire entanglement. Others suffered partial hypothermia. Having had the foresight to wear a long sleeved jersey I avoided the latter and ran a well judged race moving from twelfth to fourth place and in the run-in losing my title to Jim Fleming of MOtherwell with Jim Reid of West Kilbride second finished a creditable third. For the seventh successive year I had never been out of the first three in the National. Unfortunately I strained a muscle at the top of the thigh in the process but did not suffer the effects till after the race. Crossing the swollen stream with its loose embankment had caused it.

RAN NINE MILES WITH INJURED LEG

Physiotherapist Tom Anderson strapped my leg and I travelled with the team to Dublin. Unfortunately the injury got worse and I recall limping when crossing the road. I should never have started, but a mistaken sense of duty prompted me to run if you can call it running with one leg almost a passenger. From the point of view of performance it was the worst of my running career. But in another sense it was a near miracle thet I finished the course in 56th place with six men behind me. I sometimes feel that I never really recovered one hundred percent from that gruelling and that the lumbar trouble that has affected me from time totime originated from that day.

MIMOUN WINS BUT McCOOKE IS THE HERO.

It is often said that the loser or runner-up is never remembered. This may be aprtly but not entirely true. It is also said that the exception proves the rule. I prefer to say that the rule is not absolute. Steve McCooke, thirty one years odl, a farmer’s boiy, father of six, with two bandages on his leg and who usually races in bare feet, took the race to the elite French trio Pujazon, Mimoun and Cerou. By the end the latter’s finishing speed just prevailed and the Irish lad had to settle for a glorious fourth place. The French stars knew they had been in a race.

“THEM’S ME INTENTIONS”

After his sensational run it was McCooke the reporters wanted to interview. They suggested that after such a performance he might try to win the race outright. His reply was “Them’s me intentions.” Alas, he never did. But the man who trained on potatoes and ran in bare feet may not have got his name in the record book but to those who witnessed that race it was his performance that was etched in rainbow colours on the memory.

Many years later it was that other even greater Urish star who appeared on the horizon, John Tracey. When I first heard of him I thought to myself, perhaps the little folk have unearthed another lad from the countryside to equal and perhaps upstage the old master. Wrong! The Irish star who was to make cross-country and marathon history was a product of the American University System and received his grooming there. But there was just a slight tinge of disappointment. Romantics at heart we always hope that at least on occasion that the tale of Cinderella is not just a fairy story.

THE TRIVIA WE REMEMBER

Apart from the ups and downs of the race itself, there were some incidents of a humorous nature after that particular race. At the finish a van was dispensing liquid refreshment to the runners. Little Alain Mimoun the winner, a pathetic wistful little figure was trying in vain in broken English to attract the attention of the vn-man. As I limped forward he said “what would you like, son.” I took the refreshment preferred and with my innate sense of justice attempted to intervene on behalf of Mimoun. “This is Mimoun, the winner of the big race.”

He wasn’t impressed. “Is he indeed,” he said, “He’ll just have to wait his turn like the rest.” The man was a philistine. Then I thought of the Biblical precept. “The first shall be last and the last shall be first.”

Later in the dressing room raised voices were heard. Apparently Pujazon and his French colleagues ran as a team and the former was not amused when Mimoun sprinted away at the finish spoiling the former’s chance of winning the title three times. I know only standard French and the choice of language from the tone seemed more in keeping with that of the golf course. We got the message but were spared the intimate details. I often wonder if the great French runner who was to make Olympic marathon and tracj history recalls this early fiery baptism.

LOSERS REMEMBERED

Returning to the above, one of the classic examples of a loser being remembered rather than the winner is that of Emil Zatopek’s gallant last lap effort to catch Gaston Reiff in 1948 in the Olympic 5000m event. The stylish Belgian had opened up a forty yards lead with one lap to go but suddenly the Czech made a tremendous late charge. In a nail-biting finish the faltering Reiff just managed to hold on in a desperate finish. To the victor the spoils but the abiding memory and emotional response was captured by the courageous Zatopek who was later to make even greater history.

Even the Commonwealth marathon at Vancouver in 1954 is generally recalled as the Jim Peters marathon. His collapse in heat-wave conditions after a courageous but futile attempt to finish in a semi-conscious state captured the headlines while only athletics aficionados remember that Scotland’s Joe McGhee was the actual winner. Joe would be the first to agree that Peters was the better runner and nine times out of ten would have won. But this was the tenth occasion and Joe ran a gallant well-judged race in the prevailing torrid weather. On the other hand Jim injudiciously ran his usual aggressive pillar to post race: most unsuitable in the extremely high temperature.

I can’t resist recalling from the mists of time one more example of a dynamic and courageous failure which thrilled all who witnessed it all those years ago. It was a race I witnessed when I was a swimming enthusiast long before I took up running. The occasion was the junior championship of the West of Scotland, one hundred yards, or four lengths of the bath. Leading contenders were David McGregor of Motherwell, father of Bobby McGregor later to thrill the swimming world in the Olympics, and General David Jackson of Dennistoun. The former was a big strapping lad, the latter slim but sharp as a needle. As they turned for the last of their four lengths the big robust Motherwell swimmer had a useful lead of three or four yards and it looked all over bar the shouting. Suddenly the little Dennistoun eel cut loose and was catching his big rival, failing to do so by a mere touch. The record book can never replace memoried like these.

VETERAN’S MAGNIFICENT COMEBACK

The above examples of athletic courage in defeat remind me of one great athlete who came back from defeat to glorious victory, Jack Holden. The amazing 43 year old veteran who had to retire from the Olympic Marathon in 1948 didnot intimate his retiral from running but gave notice that he would try to prove that he was still the greatest distance runner of his day. He did just that. The programme that Jack took on would have taxed the energies of an athlete twenty years his junior. Six weeks training at one hundred miles per week. Victory in the thirteen and a half Morpeth road race.

Then his triumph in the (then named) Empire Games marathon in 2:32:57 despite running mor than ten miles barefoot when his shoes burst in atrocioua weather and being attacked by a Great Dane at twenty three miles. Returning to Britain he won the Polytechnic Marathon in 2:31:03.4 , Without pressure despite rising at 5:30 am , putting in three hours work, catching a train to Reading and walking three miles to the ground with his bag. These were indeed the days of the amateur! I knew the feeling. The following month he climaxed the seasonwith his superb victory in the European championship marathon at Brussels beating Karvonen of Finland by about 150 yards in 2:32:13.2. Holden and Vanin of Russia were together at twenty two miles and Jack recalled later that he said to himself, “This is a race between King George and Joe Stalin and Stalin’s not going to be the winner.” As one could not imagine either of those two personalities able to take part in a marathon, it was a good job the two runners took on this vicarious task.

MORE HOLDEN REMINISCENCES

Jack Holden’s main problem in running was blisters. Perhaps his feet were tender, but he had a habit of running in secially made leather shoes and I often wonder if that contributed to his problems. He was a great competitor and very self confident. One story is that he was running last in a road race relay. A runner in an opposing team had just runsuperb lap and had beaten the course record. An oficial nearby said “This record will stand for years.” Holden heard him and retorted “The record will stand for twenty minutes, I’ve still to run.” The record stood for twenty minutes! Despite Holden’s flirtation with marathon running and it may seem strange to use the word flirtation to a man winning Empire and European titles in the same year, the Yorkshire runner was essentially a cross-country specialist, un my opinion no one better, certainly in the Gaston Roelants of Belgium class. A master at getting fit for the appropriate race, he won the International title four times, more often than he won the National. Only once, in 1939 when he was 32 years of age, did he win both.

In the National he usually did just enough to make the team. His big effort was reserved for the more important International event three or four weeks later. What Holden could have done at the marathon in the modern era and at a younger age is anybody’s guess.

Although as I said at the outset, my intention was not to present anything resembling a catalogue of events and runners but merely to recall my own running career and performances good, bad and indifferent. Occasionally some specific performances come spontaneously to mind. They illustrate a particular point of interest. Mention of Holden’s run in New Zealand brings to mind Scotland’s Andrew Forbes who himself ran a heroic race in the six miles track event beaten only by local athlete W Nelson.

The fact that Andrew, now retired, is still running and a few years ago managed to return to Christchurch to compete in veteran competition is particularly worthy of mention. It highlights the fact that even when he had retired from top-class competition he was still prepared to continue in the sport which had become as it has to most of us veterans “a way of life”.