A cut above the rest

William “Cutty” Smith

by Alex Wilson

19th-century Paisley was not only an industrial powerhouse of a town, the most populous in Scotland, but also home to some of the greatest Scottish professional foot racers of all time. Some of these names may not be familiar today, long forgotten names that would have been known to our great-great grandfathers, names such as “Cutty” Smith. Smith was a native of Paisley, the eldest of 12 children born to William and Isabella Smith on 27 December 1846. The year of Smith’s birth also heralded the birth of the travel industry, when Thomas Cook from Leicester organised his first trips for well-to-do sightseers to, of all places, Scotland. 173 years later his long-running business went bust while I was putting together the material for this biography. Like most Scottish families the Smiths were far from well-to-do. Smith’s father was employed as a card-cutter at a shawl factory in Paisley, where the making of shawls had been big business ever since Queen Victoria – the fashion icon of her day – had first been sighted wearing one in 1842.

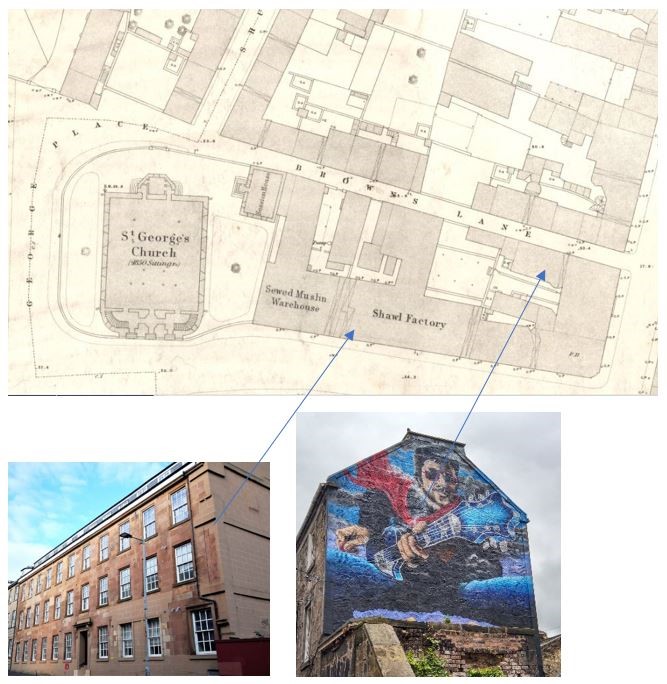

The censuses, which have been conducted every ten years in Scotland since 1841, give us snapshots of those who have long since died as well as useful clues. In 1861 the Smiths were to be found living in a tenement at 5 Brown’s Lane in Paisley. The building has miraculously survived the waves of urban redevelopment that have swept over Scotland in recent times erasing forever much of the original character of old towns like Paisley. In fact, it is now something of an underground attraction thanks to a graffiti mural of the late Paisley-born rock deity Gerry Rafferty gracing its gable end. The adjacent property is identified on old street maps as a shawl factory, which was probably where Smith snr. and jnr. were employed. The building has since been converted for residential use and the handlooms that once echoed within these walls are now museum pieces, silent witnesses to the past. It being the custom back then to follow in one’s faither’s footsteps, Smith also joined the ranks of the card-cutters. His job was to transfer intricate designs to punch cards which were used on Jacquard looms to create fabrics with the famous “Paisley pattern”.

Quite how Smith came by his unusual sobriquet is unclear. In Scots “cutty” translates to short, stumpy or diminutive, as in “cutty stool”. Well, Smith tipped the scales at 8 stone 12 lbs. (56 kg) and stood just under five feet six inches tall (1.67 m), diminutive today but not in 1870. A “cutty” is also Scots for a fast-moving, scrawny rodent with long limbs: the common hare. See the connection? To confuse matters, a “cutty” was also a short-stemmed clay pipe popular then among tobacco smokers, but that seems an unlikely source for his name. Could “cutty” simply have been a vernacular reference to his occupation? It’s anyone’s guess!

Smith not only had a distinctive moniker but also a distinctive running style for it appears that he ran on the flat of his foot with a fast, low stride and some forward lean. There was nothing stylish about his running style, but style doesn’t necessarily win races today, and didn’t then either.

On 21 May 1869 Smith contested his first notable race at the Stonefield Recreation Grounds in Glasgow. It was a three-mile handicap promoted by the Glasgow Pedestrian Club. He started from a mark of 330 yards but failed to make much of an impression. Two months later, however, he took on the reigning Scottish 10-mile champion Willie Park (not to be confused with the famous golfer) in a three-mile handicap at Kelvinside Recreation Grounds and won easily off 100 yards in a time of 15:33.5. In those days, news spread by word of mouth almost as quickly as it does today through social media. By the summer of ‘69 he was toeing the scratch mark at Highland meetings.

This old town plan of Paisley shows the house and the shawl factory in Paisley where Cutty Smith once lived and probably worked, while the pictures below show how they look today.

The subsequent summers would fly by in a blur of races as Smith skipped from one meeting to the next in relentless pursuit of prize money. These were heady days for the professional runner, when a buoyant economy brought increasing prosperity and opportunities galore to those with the wherewithal seize them. In a dog-eat-dog world where even the smallest competitive edge could make all the difference, hitherto neglected aspects such as training volume and intensity, post-training massage and diet became increasingly important. There was no such thing as a training manual in those days. This meant that trainers purported to be knowledgeable in the arcane science of physical conditioning were much sought after. In fact, no self-respecting “ped” was ever what we would term “self-coached”. Smith was trained by Jock Lindsay, a diminutive Glaswegian taskmaster about whom little is known, but it may be assumed that he trained his charges to within an inch of their lives. Another well-known trainer of the time, Harry Wyatt, professed to “work off all the adipose tissue” of in runners in his care so that there was, quote, “nothing left but muscle and sinew”.

Smith’s first big match was on 8 October 1870, when he raced Willie Park at Greenhill Cricket Ground, Paisley, for £30 and the “Ten Miles Championship of Scotland”. 3,000 “Buddies” braved cold and windy weather to witness their new distance-running sensation take on the Scottish champion. They would be rewarded for their efforts when Smith romped to victory over the veteran Glasgow ped by about 250 yards in 57:30.0. By now it was clear that if Smith could run this fast on a grass track in bad conditions, he could aspire to greater things. Even at this early stage of his running career, Smith seems to have had a penchant for injecting sudden and frequent bursts of pace with the sole purpose of exhausting and/or demoralising his opponents. It was to become his trademark tactic. Sometimes it and worked sometimes it backfired. Some may recall that Brendan Foster employed such a strategy in the 5000 metres final at the 1974 European Championships. To see some snippets from this race, click on this this link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tIumqbnwokc&t=11s.

The 1871 census, the next snapshot of Smith’s life, records that he is unemployed and living with his 21-year-old wife Margaret next to his parents in a tenement building on Love Street. This census was enumerated in early April, which of course was during the off-season for the professionals who competed on the Highland Games circuit. Without having to spend 60 hours a week cutting cards, he could of course devote himself entirely to training. By the same token, his winnings from the previous summer had to last until the next season, but these were no doubt substantial enough. On 1 July Smith got the summer off to a good start by soundly defeating Willie Park and Jemmy McLeavy in a three-mile flat race on grass at Greenock in 16:30.0. The Greenock Telegraph reported that “Smith, of Paisley, who came in first, showed some beautiful running.” It was not long before Smith was ready to take it to the next level. On 16 October 1871, he made his first appearance in London, in a four-mile handicap at the Lillie Bridge Ground, one of the meccas of 19th-century pedestrianism. Starting as a nobody from the 550-yard mark, he produced a sterling performance and won by 150 yards in 19:25.0. By defeating 28 other runners, including a few well-known peds into the bargain, it had taken him less than twenty minutes to get his name on the board, as it were.

Despite his promising success at Lillie Bridge at the end of the 1871 season, 1872 was to be a quiet year for Smith. Outside of the Highland meetings, he contested only three major races. The first of these was at the Queen’s Birthday Meeting at Powderhall on Thursday 23 May. Here he ran off 95 yards in the mile handicap and took the first prize of £10 ahead of Willie Park and Bob Hindle. He followed this up on 24 August with a second-place finish in the six-mile championship at Powderhall, where he finished in second place, 350 yards behind Jemmy McLeavy in an estimated 32:38. Finally, on 30 September, he placed third in the one-mile championship at Gateshead Borough Gardens Grounds behind Hindle and McLeavy in an estimated 4:34.4.

In 1873 and 1874, Smith eschewed big races and matches and confined his appearances to Highland meetings, the number of which was increasing steadily from year to year. Such was the proliferation of Highland meetings by now that on some weekends Smith had a choice of multiple options. The summer of 1874, for instance, saw him in action in Highland meetings at Kilbirnie (200 yards, 1 and 2 miles), Greenock (1 and 3 miles), Wishaw (1 and 2 miles), Paisley (1 and 2 miles), Forfar (880y and 1 mile walking match), Whitburn (1 and 2 miles), Galashiels (1 and 2 miles), Kilbarchan (mile), Leith (mile), Couper Angus (1 ½ and 3 miles), New Cumnock (3 miles), Clackmannan (880y and 2 miles), Alloa (mile heat + final) Pollokshaws (4 miles), Methil (1 and 2 miles), Springburn (half mile and mile), Dumfries (1 and 2 miles), Bridge of Allan (1 and 2 miles), Cupar (1 and 2 miles), Birnam (500y three-legged race) and Ardrossan (1 and 2 miles). If anything, this list is incomplete. However, it gives a good idea of how busy Smith’s typical summer racing schedule was. The Greenock Telegraph, in its report on the 1874 Greenock National Games, commented: “The three-mile race (handicap), for which Wm. Smith, Paisley, Park, and several other peds were entered, was the one that caused the most enthusiasm. From the first it was thought that Smith would be the successful man, and so it turned out. Smith is still as fleet as ever, and steps it very quickly, without losing that vigour which is noticeable in many of these “professional” men. Starts of different lengths were given to the whole of Smith’s opponents, but one by one he passed them, and came in a winner with the greatest of ease.” Wherever he competed on the Highland Games circuit, as a star attraction Smith invariably took home a share of the prize money, though rarely more than five pounds in total. Of course, he had to pay his travel expenses, and his coach and any attendants would also have taken their cut. Yet he had no trouble earning several times an ordinary labourer’s average weekly wage (30 shillings, give or take) in a single afternoon. In order to pull in as big a crowd as possible and thus maximise revenues, the hosting communities were always looking to attract well-known sportsmen to their annual meetings: the more famous, the better. In keeping with the general business rule that a happy customer is a regular customer, the handicap races at the Highland meetings were typically framed in such a way that the “cracks” had a reasonable to good chance of winning outright, or at least making the prize list. To conserve his energy, Smith rarely did more than necessary, and when he won, he often did by a margin of no more than 20 yards. The handicaps at key venues such as Powderhall Grounds in Edinburgh or Lillie Bridge Grounds in London were of course a different matter altogether. They usually had a much bigger single-race purse and were framed more rigorously, that is to say more objectively. As such, it was not uncommon for a leading ped to finish well down the order and go home empty-handed. Of course, peds were risk takers by nature, and the potential upside would have outweighed the potential downside in their eyes. This was the case with an open handicap at the Queen’s Park Recreation Grounds in Glasgow on 3 October 1874, a race in which Smith celebrated his biggest payday of the year – a first prize of £13 in the two miles off 30 yards.

In 1876 Smith began to include more big races and matches into his racing schedule, a change of heart motivated presumably by pecuniary considerations. The 1870s saw a plethora of enclosured running tracks opening throughout the British Isles, several of them in Glasgow alone – such as Springfield Recreation Grounds. Here, on 29 April, Smith took on Willie Park in a 10-mile race for £30. Smith had conceded the Glasgow veteran a start of 440 yards but was in such fine fettle that he caught his opponent before the halfway mark and won by half a mile in 55:41.0. To rub salt in the wound, he also broke Park’s Scottish record of 56:19.75 set eight years earlier at the former Stonefield Recreation Ground. Two weeks later Smith returned to Springfield to compete in another 10-mile race, this one being the grand-sounding “Great Ten Mile Race for the Championship of the World”. The contest was to be decided between himself, George Hazael, London, and Alick Clark, Glasgow, with prize money of £50, £15 and £5 for the first three. Hazael was evidently “in the pink” for he set a fast pace from the start and forced Clark to call it quits after only a mile. Having said that, Clark had probably expected to come third anyway! Smith held on to Hazael’s coat tails for as long as he could, but he too was forced to retire, albeit after eight miles. Hazael won unchallenged in an outstanding time of 52:05.0, only 39 seconds outside the world record set by the famous Seneca Indian Lewis “Deerfoot” Bennett in 1861. On 23 September, after a long summer of racing, Smith appeared in a four-mile handicap at the Powderhall Grounds in front of about 5,000 spectators. The proprietor, Mr. Charles Robertson Bauchope, had offered a silver champion cup plus £25 for the winner. Instead of yards, the starts were allotted in minutes and seconds – just like in a modern biathlon pursuit race. All competitors therefore were required to complete the full distance. Anyone breaking the world record of 19:36.0 was to receive a bonus of £50. A sovereign was also to be given to each of the competitors who completed the distance in under 21 min. 30 sec. and an outrageously generous 5 shillings to everyone who “competed the distance without stopping”. The Sportsman takes up the story from here: “Punctually at five o’clock the bell rung for the big race, betting on which had been freely indulged in throughout the afternoon. Those most in demand were Smith, of Paisley, and Bailey, of Sittingbourne, who were each supported at 7 to 2. The others were accorded prices ranging from 6 to 1 to 20 to 1… Out of an entry of thirty, twenty faced the starter. There was loud cheering when it came to the turn for the two favourites to be dispatched, and for nearly half-way the race was a fine one. After that, however, the local novices, who had never attempted so long a journey before, were in difficulties, and the scratch men overhauled them with astonishing rapidity. Till three miles and a half had been covered Smith and Bailey raced abreast, but in the last two circuits the Sittingbourne man came right away and won cleverly by a score yards; time 20min 38sec.” The adjusted times were 21:01.0 for Bailey and 21:05.4 for Smith, who took home £5. McLeavy, who started from scratch, finished third but was disqualified for “jumping the gun” (he had started no fewer than eight seconds too early!).

Even in the autumn of 1876 Smith refused to let up – quite the opposite in fact. On 7 October he outstripped a good field including McLeavy in a three-mile handicap off 100 yards at the Vale of Clyde Grounds in Glasgow. A fortnight later, he defeated John Beavan from Camberwell in a 10-mile match for £30 at Springfield. Then, on 16 December, he entered a challenge cup race at Springfield Grounds over a mile – not a distance he was known to excel at. The Edinburgh Evening News sums it up nicely: “The race was for a silver challenge cup, value £15, with £15 added money, the second to receive £4, and the third £1. The twenty-six competitors toed their respective marks, and a capital start was affected. In the home straight, W. Smith, 70 yds. start, rushed to the front and came in an easy winner by four lengths; Eldred, of Glasgow, 80 yds. start, was second, ten yards ahead of Taylor, Glasgow, 115 yds. Time, 4 mins. 24 secs.” No one would have been more surprised by this outcome than Smith, who would probably have been the first to admit that he wasn’t much of a miler. This race having been run under challenge cup rules, he had however only taken the first step to outright ownership of the cup. He had to win it twice, including the handicap, the winner to be penalised ten yards and to run every six weeks if challenged for not less than £15 a-side. The following week, Smith made the long journey south and spent Christmas of 1876 at a London hostel in preparation for a 10-mile handicap on Boxing Day at Lillie Bridge for prizes worth £50. Smith had been given a start of 1 min. 30 sec., with only McLeavy behind him on scratch. The Sporting Life reported merely that Smith had taken the lead in the last mile and secured the £30 first prize ahead of J. Tester and Blower Brown. Another £10 was divided among those who ran the 10 miles within the hour (eight in all). Smith’s time of 53:22.0 was the fastest in Britain that year and a significant improvement on his own Scottish record.

Smith kicked off the 1877 season on New Year’s Day at a chilly Vale of Clyde Grounds, where he finished third in the four-mile handicap off 90 yards in 20:42.5. It was a good performance for this time of year and indicative that he was keeping himself in shape for an imminent – albeit improbable – defence of the mile challenge cup. The second race for the “Mile Handicap Silver Cup” was in fact decided on Saturday 24 February 1877 at Springfield Recreation Ground, where Smith faced no fewer than five challengers, each man having paid £15 into a sweepstakes, making in all £75 in addition to the cup. Having been penalised 10 yards for his earlier win, Smith on this occasion started from the 60-yard mark, his chances diminished. However they forgot to tell Smith, who caught the last of the runners in front of him at the apex of the last bend and uncorked an inspired sprint that carried him to victory by 10 yards in 4:37.25 ahead of a young William Cummings. Having won the challenge race twice in a row, the silver cup became Smith’s absolute property. Financially, it was by far his biggest win to date.

On 2 June, Smith took on Peter Simpson in a four-mile match for £40 at Shawfield Recreation Grounds. During the previous two seasons, the Edinburgh runner had figured prominently in the east and south of Scotland and built a formidable reputation, having already beaten Smith in the previous year in an open two miles at Kelso. This time, however, Smith would turn the tables on his east-coast rival. The North British Daily Mail reported: “There was a fair attendance on Saturday to witness the four-mile race between Wm. Smith, Paisley, and Peter Simpson, Edinburgh, for the sum of £40. They alternately led to the last quarter of a mile, when the pair got level and ran alongside each other till about 180 yards from home, when Smith began a tremendous spurt and won by 20 yards. Time, 20 min. 58 secs.” To make the most of his good form, Smith returned to Shawfield four weeks later to defend his title in the Ten Miles Championship of Scotland against McLeavy. On paper at least, Smith was no match for McLeavy at distances up to four miles, but over 10 miles they were thought to be closely matched. The surface was rutted following mid-week trotting races, but that didn’t deter Smith from scorching through the first mile in 5:02. He then proceeded to inject a spurt every half mile and took care to not let the pace slip, leading through four miles in 21:03, five in 26:36 and six in 31:58. At one point McLeavy appeared to crack, but the Alexandria ace rallied and closed the gap again before sprinting past Smith on the home straight to win a thrilling contest by two yards in 54:10.0. Arguably Smith had done himself more harm than good with his spurting tactic, always a dangerous strategy against such accomplished a performer as McLeavy. On 7 July, despite a busy schedule of Highland meetings during the summer, Smith found the time to take on Glasgow’s Paddy Corbett in a 10-mile match for £30. He had conceded this opponent half a mile and would probably have caught up with him had he not lost one of his spikes, forcing him to retire at seven miles. Then, on 23 August, Smith made his first appearance in the famous Red Hose Race at Carnwath in south Lanarkshire. This race, a half-mile dash through the village, is today the oldest in the United Kingdom and the second oldest in the world, dating all the way back to 1508. However, a win it was not to be, the coveted red socks going to Edinburgh’s half-mile specialist William Mann.

On Saturday 20 October, Smith took part in yet another four-mile handicap against a strong field in front of 2,000 spectators at Springfield Recreation Grounds. He had received a 15-second start and was one of the bookmakers’ favourites at 4-1 against. In a thrilling contest he caught the race leader George Cameron 200 yards from home and sprinted to victory in a time of 20:24.5. If you add his start, his net time was 20:39.5. There was also some drama when Alex McPhee, Paisley, father of 1920 Olympian Duncan McPhee, pushed James Bailey (Sittingbourne) off the track at 2 ½ miles. As the runners came into the home straight, the referee stepped onto the track and removed McPhee amid loud cheering and banished him from the ground for six months. Rioting was not uncommon at professional meetings as such events tended to attract a highly volatile element with a dangerous inclination to drink and gamble. To avoid crowd trouble, fraud of any kind had to be seen to be sanctioned with an appropriate measure of severity.

Having confirmed his good form, Smith signed articles for a match against Jemmy McLeavy to decide the 10-mile championship for £50 and a champion belt. The race was supposed to take place at Shawfield Recreation Grounds on 10 November but failed to materialise when Smith contracted gastric fever and was forced to forfeit, giving McLeavy the luxury of a walk-over. Thus ended the 1877 season.

The 1878 season began with the sensational news that the famous M.P. and sports patron Sir John Astley would be bankrolling the world’s first six-day “go-as-you-please” race in which the competitors could run or walk at their leisure. The event was to take place at the Agricultural Hall in London’s Islington district on Sunday 18 March. The total prize money was to be £750, and the winner was to receive a champion belt worth £500 plus an additional £100 in prize money.

Smith had no experience of ultra-long distances, but like his compatriot Jemmy McLeavy, he was drawn like a moth to the flame by the mouth-watering prize money. After recovering from the illness that had beset him in late 1877, he began the extensive preparations for the upcoming six-day race. As early as February he was already looking for races to test his form. On 2 March he challenged Jemmy McLeavy for the Ten Miles Championship of Scotland and £30. The match, which was decided at Shawfield Recreation Grounds, was not much of a contest though as Smith broke clean away from McLeavy at five miles and won by half a lap in 54:42.0. Poor McLeavy suffered not only a heavy defeat but also had to endure the jeering of his so-called “supporters”. A week later, they met again at Shawfield Grounds for an 8-hour “go-as-you-please” race. For both of them it was the first real endurance test before the upcoming Astley Belt race just nine days in the offing. The two opponents alternated between walking and running. After 6 hrs. 40 min. the race was discontinued due to the onset of bad weather, Smith winning by 4 miles having covered 39 miles (62.8 km).

The six-day Astley Belt race began on the scheduled date in the presence of a huge crowd. Two tracks had been constructed from brick gravel, sand, tan bark and earth. One, 7 laps per mile, was for the British and Irish entrants while the other, 8 laps per mile, was for foreign entrants (which meant that the American Dan O’Leary had the track all to himself). Each competitor had his own trackside cubicle equipped with a bed and a stove, very basic. Smith was up against 17 other competitors of varying abilities and experience and immediately showed that he lacked the latter by taking an early lead, covering 9.1 miles in the first hour, 20 miles in 2:24:22 and 23.45 miles in 3 hours. This was of course a suicidal pace, and after only four hours (28.1 miles) it began to take its toll. As fatigue set in, he could only watch as his more experienced rivals overhauled him one after another. In the end, he wound up 13th with 198 miles on the scoreboard – 322 miles fewer than the winner, Dan O’Leary.

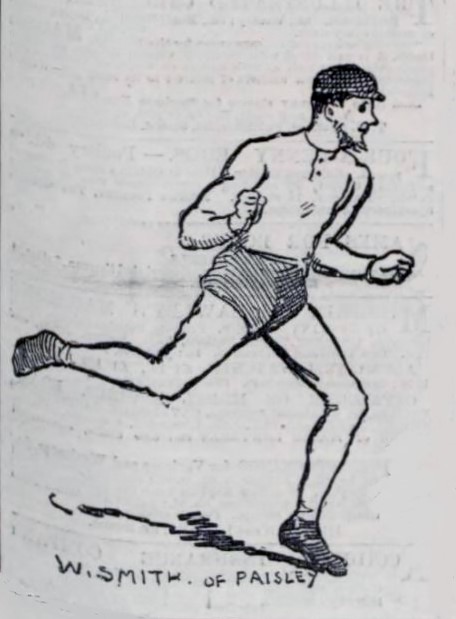

| This engraving from Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News is believed to depict Cutty Smith. |

In the run-up to the Islington six-day race Smith had ramped up his training quite considerably. Although the hoped-for success had failed to materialise, the gruelling contest had taught with valuable lessons and insights into the realm of six-day racing, not to mention providing him with a good endurance base for the coming season. His first opportunity to test this theory came on Monday 13 May in a six-mile championship sweepstakes against Hazael and McLeavy for £40 in front of 2,000 spectators at Springfield Recreation Grounds. The race featured heavy betting with odds of 6 to 4 against McLeavy, 2 to 1 against Smith and 4 to 1 against Hazael. According to the Glasgow Herald, it unfolded thus: “Postponements as a rule seldom do well, but that of Springfield Grounds the change the change on Saturday till yesterday evening proved an exception as fully 2000 assembled to witness the six-mile championship race between William Smith, of Paisley; James McLeavy, of Alexandria; and George Hazael of London – the prizes being £50 and £10. The men looked well, and before they started the betting ruled 6 to 4 on McLeavy, 2 to 1 agst Smith, and 4 to 1 Hazael. The lot got away well, Smith and McLeavy alongside each other, travelling about two yards in advance of Hazael; but after going 700 yards Smith dropped to the rear, and on passing the referee for the first time McLeavy led by two yards, Smith last eight yards in rear of Hazael. After going half-a-mile Hazael showed signs of distress, and fell far behind. At the finish of the three miles the Londoner retired, when about 400 yards in the rear. McLeavy showed the way till the close of the next quarter, when Smith put it on and came up alongside the leader, and the pair ran for fully 100 yards locked together. Coming up the straight, Mac shook the Paisley representative off, and led at three and a-half miles by six yards. In the succeeding lap Smith shot past, and was never afterwards in danger – in fact, he held such a lead that McLeavy, at five and a-half miles, seeing his chance hopeless, gave in. Smith, therefore, finished, alone. Time – 1st mile, 4 min 44 ¼ sec; 2nd mile, 9 min 56 ¼ sec; 3rd mile, 15 min 20 ½ sec; 4th mile, 20 min 41 sec; 5th mile, 26 min 3 ½ sec; 6th mile, 31 min 29 ¼ sec.” This performance, which was just a shade outside McLeavy’s Scottish record of 31:28.0 set in 1872, was the fastest time recorded in the world that year. The six-day race had not been a fruitless exercise after all, for the extra work he had put in during the winter had clearly done wonders for his running at the shorter distances he favoured. It almost goes without saying that McLeavy was intent on securing a rematch race against Smith and the chance to avenge his defeat. On June 8, they met again in a six-mile race at for £25 a-side at Springfield Recreation Grounds. The Sporting Life reported: “McLeavy had been taking his breathings at Bothewell, while Smith trained on the ground. During the last few days rumours were circulated that McLeavy had broken down, which caused Smith’s friends to lay 3 to 1. The proprietor got the men to their marks in good time, the rain coming down in torrents for about ten minutes. Smith went away with about five yards’ lead, and in this manner they finished the first mile in 4 min. 47 sec. At no part of the race would McLeavy try to get to the front, despite the frequent rushes of Smith. When the men had got about three miles, they were like a pair of darkies, covered with mud, with McLeavy still in the rear; in this order they continued until coming into the straight for home, when a splendid race took place, McLeavy winning by about two yards in 31 min. 34 ½ sec.” The mile splits were: 1M – 4:47, 2M – 9:52, 3M – 15:10, 4M – 20:35, 5M – 26:19. So there it was. McLeavy had levelled the scores again.

A few days later Smith headed south to London to compete in the British 10 Mile Championship at Lillie Bridge. The stadium was home to the country’s best cinder track. It was also one of the longest tracks in the British Isles, measuring 586 2/3 yards per circuit. Sir John Astley, that great patron of the sport, had promised the winner a champion belt worth 50 guineas and a medal worth £5 plus a third of the “gate”. The bookies made Smith their favourite ahead of George Hazael, Deptford, William Shrubsole, Cambridge, James Bailey, Sittingbourne, and Charlie Price, Kensington. Though a good race was in prospect, the public was clearly of a different opinion as the attendance was much less than expected. Smith led for the first three miles and then gave way to Price for the next three miles before regaining the lead at seven miles. The race was finally decided when Smith injected a burst of pace that carried him to victory by 50 yards in 53:42.5 ahead of Bailey (53:53.0) and Price (53:58.0). The mile splits were: 1M – 4:45, 2M – 9:56, 3M – 15:13.5, 4M – 20:45, 5M – 26:06, 6M – 32:05, 7M – 37:14, 8M – 42:49, 9M – 48:27. Smith, however, did not enjoy being the British champion for long, as he was unable to raise the necessary stake when Hazael challenged him on 15 July. Consequently, he was compelled to default and hand over the belt to Hazael.

George Hazael

Having ruled out a defence of his British 10-mile championship, Smith entered the 50-mile British Championship sponsored by Sir John Astley at Lillie Bridge on July 15. The race was for a challenge belt worth £50 and cash prizes totalling £35. However, attendance was again low – only 400 spectators came. The race started quickly, as Hazael had bet on completing the first 10 miles in under an hour. The Deptford runner immediately took the lead and covered the first five miles in 27:02 and the first 10 miles in 56:35. At 15 miles, he was still well ahead in 1:27:38, but then he lost a lot of ground during the next 5 miles, allowing Smith to make up half a mile and get back on level terms. With his opponent going through a bad patch, Smith moved ahead in the 20th mile, which he completed in 2 hrs. 10 min, and kept the pace ticking over to 25 miles, where the standings were: 1 – 2:50:22, Cutty Smith; 2 – 2:51:22, James Bailey (Sittingbourne); 3 – 2:53:50, Harry Vandepeer (Sittingbourne). Although blissfully unaware of his feat, Smith had become the first man to run 25 miles in under three hours. However, his race came to a grinding halt at 30 miles when he suffered a bad attack of leg cramp, and a resurgent Hazael bounced back to take the title in 7 hrs. 15 min.

During a busy summer, Smith won, among other things, a one-hour race in Forfar on 9 August, with a distance of 10 ¼ miles, and a traditional “basket-and-stone” race ahead of David Livingstone at the Springfield Grounds on 17 August. In the Scottish Six-Mile Championship at Springfield Grounds on October 12, however, he trailed home second 115 yards behind Livingstone in a time of around 32:13.

So that was it for 1878, a year which, despite the disappointment of the six-day race, had nevertheless been his best yet, a year which had seen him claim several major victories, notably the 10 Mile Scottish Championship and the British Championships over 6 and 10 miles, as well as setting a “world record” for 25 miles.

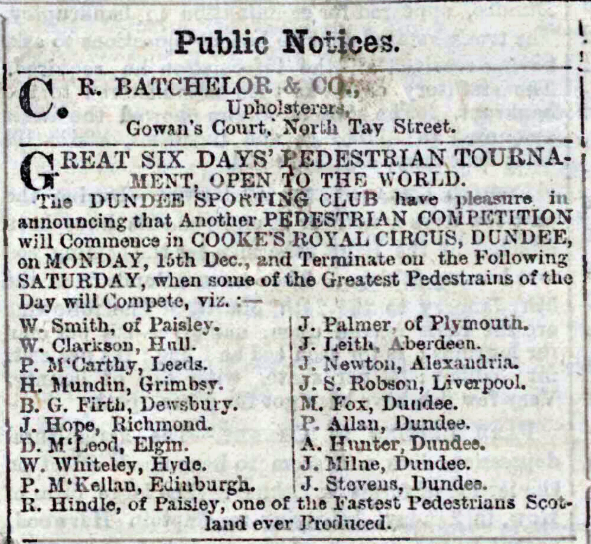

When six-day racing boom hit Scotland in 1879 Smith was one of several prominent peds to move up. First and foremost, there was the prize money, not least thanks to the popular novelty value of this new racing format. Then there was the fact that these contests were staged indoors during the winter, which was otherwise the lean season for most peds. The popularity of six-day races was so great that promoters all over the country were vying for the attention of the best peds. Smith immediately saw his opportunity. Since George Hazael, Alick Clarke and Jemmy McLeavy, among others, had likewise switched to six-day races, 1879 was to be a year largely devoid of long-distance championship races over the usual distances from 4 to 10 miles. In early January 1879, Smith was one of the 15 starters of a 48-hour go-as-you-please at the Aberdeen Music Hall, where the first prize was a gold medal and £10 in cash. When the race started on Thursday evening, the hall was packed to the rafters with spectators. The track was a dizzying 22 ½ laps to the mile, so competitors were asked to overtake on the outside and change direction every hour. For some participants, 50 miles was sufficient, as it entitled them to have their entry fee returned. However, Smith, who took the lead early on, had other ideas. By covering 92 miles in the first 24 hours and 66 ½ miles on the second day, he ultimately won by seven miles from Joe Leith, a local cattle drover with no foot racing pedigree. In late March, Smith joined forces with Jemmy McLeavy in a 24-hour walking match against Peter McKellan (Edinburgh) at Shawfield Recreation Grounds. Both Smith and McLeavy had to walk for 12 hours at a stretch, while the 45-year-old ex-soldier, an acclaimed heel-and-toe specialist, was to walk the whole distance alone. Smith was first up and covered 55 ¼ miles in the first 12 hours but was unable to keep up with McKellan, who was four miles ahead. McLeavy managed 53 miles during the allotted time, but the aggregate effort of the pair proved enough to defeat the amazing McKellan, albeit only by two miles. Although neither Smith nor McLeavy was particularly proficient at walking, their training would most likely have consisted of a mixture of running and brisk walking in primitive running shoes that afforded next to no shock absorption. To capitalise on the popularity of endurance running at the time, the Aberdeen Highland Games Organising Committee included a five-hour “go-as-you-please” for a first prize of £5 5s in their programme of events on Saturday 19 July. Once again Smith emerged as the winner after having covered 35.1 miles. But he had to dig deep to fend off Daniel McLeod, a young cartwright from Elgin. When the meeting resumed three days later, Smith shared first prize in a one-hour walking race, covering 6¼ miles (about 10 km), which would still be a respectable achievement for a runner today. Towards the end of the year, as he gained more and more competitive experience and developed his basic endurance, Smith tried his hand at six-day races again. In his first six-day race of the winter, a 72-hour race (12 hours per day) at Wolverhampton’s Agricultural Hall, starting on 14 November, he finished in second place with 357 miles behind Sam Day and took home £30 prize money. Making his debut in fourth place was George Littlewood from Sheffield, who nine years later would set a fantastic six-day world record of 623.6 miles in New York. A month later, Smith entered another 72-hour race for a first prize of 50 pounds at Cooke’s Circus in Dundee. The Cookes were a family of circus artists who operated circuses around the country. The Dundee venue was opened in early 1878 on a site behind the Queen’s Hotel in Nethergate. The luxuriously appointed building was 37 metres long, 24 metres wide and 18 metres high and could seat 3,500 spectators. The ceiling was decorated from wall to wall with oriental tapestries, and for the comfort of the guests there were upholstered seats and velvet floors. Lighting was provided by two rows of gas jets and six stylishly arranged chandeliers. The race was run on a raised tan bark track measuring only 50 yards a lap or 35 laps to the mile. The entrance fee was two shillings per day for the reserved seats, one shilling for the promenade and sixpence for the gallery. To cut a long story short, Smith repeated his performance from Wolverhampton with 358 miles, but it was easily enough to win him the race on this occasion.

Just a fortnight after his win at Dundee, Smith returned to Aberdeen to contest the Scottish Six Day Championship at John Henry Cooke’s Royal Circus on Bridge Street, a decade-spanning event that began on 29 December 1879 and concluded on 3 January 1880. Being the Scottish championship, only bona fide Scots were eligible to compete. There were 16 entries and the winner was to receive a handsome champion belt and £20 in cash. The champion belt was hand-crafted from black velvet trimmed with red silk and mounted with five plates of solid silver. A male figure running was engraved on each of the two side pieces with a handsome border of rose, thistle and shamrock. The two front clasps contained the arms of the City of Aberdeen and “Bon Accord” and the massive centrepiece bore the inscription “Six-days’ Long Distance Champion Belt of Scotland”. The track was tiny at 43 yards per lap or 41 laps to the mile, so the lap counters had to be on their toes lest they miscount. But as tiny as the track was, it was not as small as the track at Perth Drill Hall, a nausea-inducing 43 laps to the mile. One of the participants, James Robson, was actually a Scouser, but his hopeless attempt at a Scottish accent gave him away and he was disqualified. He protested to little avail, claiming he was from Berwick-upon-Tweed. Smith was the bookies’ favourite and took the lead early on. By alternating between running and walking he made 66 miles in the first 12 hours. Then on the second day he covered 64 miles, on the third day 63 miles, on the fourth day 59 miles, on the fifth day 49 miles and on the last day 45 miles. In the end, he won by a huge margin of 27 miles with a total distance of 347.9 miles. By popular request of the spectators who chanted “Put it on”, Smith embarked on a lap of honour proudly displaying the championship belt.

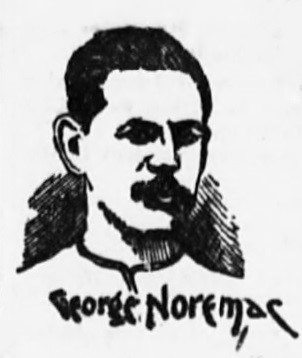

On 28 February 1880 Smith took part in his fourth 72-hour race in as many months at Newcome’s Circus in Glasgow, but this time he failed to reproduce the form he had shown towards the end of 1879. With a total score of 337 miles, he had to settle for third place behind Edinburgh’s George D. Cameron (aka Noremac) and Peter McKellan, who made 357 miles and 348 miles respectively. With the six-day craze now in full swing, Smith did not have to wait long for the next competitive opportunity to come along: a 72-hour go-as-you-please at the Edinburgh Royal Gymnasium on 29 March. There were eight participants competing for total prize money of £70 and the winner was to receive £40. The track measured a 125 yards per lap or 14 laps to the mile. Suffice to say that Smith was unlucky: during the first two days he suffered not only constipation but also unbearable pain in his right leg, necessitating the application of a cast. Despite all this, he still managed to cover 158 miles before finally discretion prevailed over valour. Consequently, he played no part in the best 72-hour race ever, a thrilling encounter in which Noremac triumphed over Davie Ferguson in front of a home crowd with a sensational score of 384 miles.

On 8 May Smith was back in action at Springfield Recreation Grounds, where the main attraction was a ten-hour “go-as-you-please” featuring Smith, Noremac and Davie Ferguson. The race was held in hot and dusty conditions, which caused the participants (eight in all) great difficulties, so it was discontinued by mutual consent after 9 hrs. 25 min. Smith took second place with 59 miles (95 km) behind Ferguson (61 miles / 98 km), but ahead of Noremac. On 21 June Noremac and Smith again were to the fore in a 26-hour six-day open-air race at the recently opened Aberdeen Recreation Grounds. The winner was to receive £40 and the runner-up half that amount. Both Smith and Noremac were evidently in fine form. Despite covering 34,875 miles in the first 4 hours (equivalent to a marathon pace of 3:00 hours), Smith was unable to shake Noremac off. In the end Noremac won with 204.6 miles to 201.2 miles for Smith. Third- placed Harry Mundin from Hull (180 miles), and fourth-placed David Ferguson from Pollokshaws (165 miles) were, reported the Aberdeen Weekly Journal, “pupils of Smith”, who “expressed himself pleased with their success”.

Shortly after that, Smith completed an extensive schedule of Highland Meetings, highlights of which included a 3-hour “go-as-you-please” in Aberdeen on 17 July and a 6-hour “go-as-you-please” in Kendal on 3 August. In the former, Smith won narrowly from Daniel McLeod by covering 25 ½ miles (41 km). Unfortunately, he was not so successful in Kendal against the likes of George Cartwright and George Mason and dropped out of the race after covering just over 36 miles (58 km). In Smith’s defence, it is worth noting that there were only 16 days between these gruelling multi-hour contests, and in that time he managed to complete no fewer than seven races between 1.5 and 4 miles.

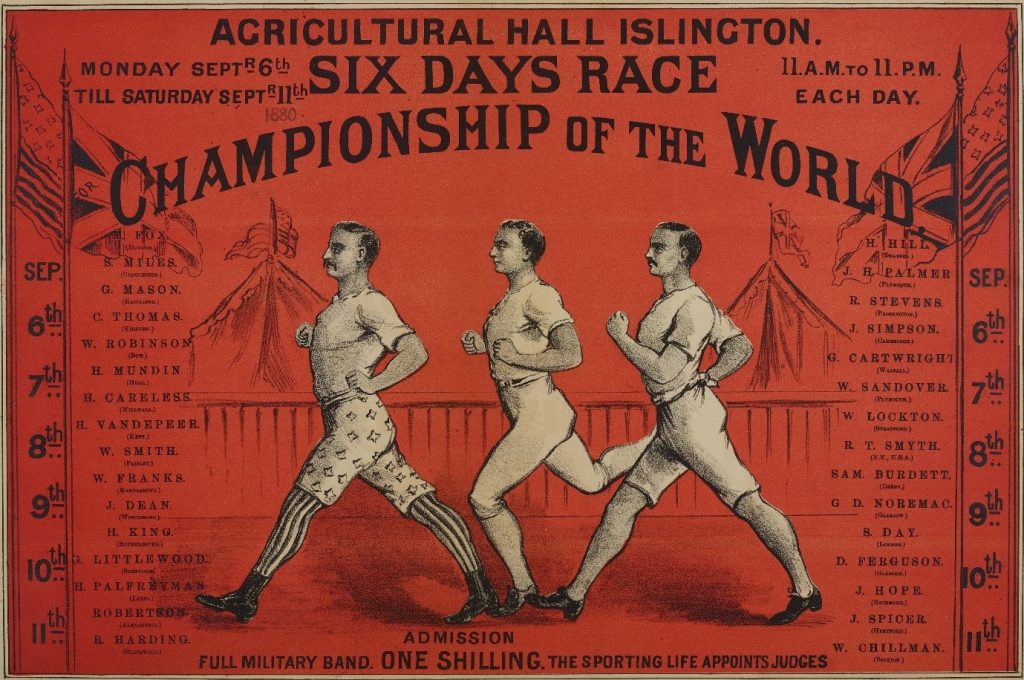

Courtesy of Islington Local History Centre

In the meantime it had been announced that there would be another six-day race (a 72-hour race) at the Agricultural Hall in Islington, from 6-11 September. There were to be very valuable prizes on offer, plus a champion gold medal from Sir John Astley. Smith’s entry was accepted and at 11 a.m. on September 6 he lined up against 28 other competitors. The starting list read like a who’s who of six-day racing. On day 1, he covered 33.3 miles in the first 5 1/2 hours and after 12 hours he was in 11th place with 65.4 miles. The second day, however, marked the end for Smith and dashed all hopes of a share of the prize money. In the end the victory went to George Littlewood, who won emphatically with 406 miles. Smith’s protégé Harry Mundin finished fourth.

In 1881 Smith vanished completely from the scene. It was reported that he had gone to America, as had his great rivals George Hazael and James McLeavy. Unfortunately, I was unable to find any records of any races Smith may have done in the USA nor can I give any information about his activities or whereabouts. The lack of data would however suggest that his visit to the USA was hardly successful. In 1882 he returned to Scotland and continued his running career at the age of 35.

After a handful of low-key races Smith marked his return to big stage on 1 September 1883 with a 10-mile match against Davie Livingstone for £30 at Shawfield Recreation Grounds. Both men had been quiet for a long time. Livingstone hadn’t run a 10-mile race for three years since losing to Willie Cummings at Lillie Bridge. The interest in this clash between these two greats of the Scottish pedestrian scene was correspondingly great. As the Paisley Gazette reports, Smith did not disappoint: “Notwithstanding the disagreeable weather on Saturday afternoon, there was a good attendance at Shawfield Running Grounds, Glasgow. The principal attraction was a ten-mile race between D. Livingstone, of Tranent, and W. Smith, of Paisley, the latter getting 250 yards of a start…Betting opened 6 to 4 on Smith, but even money was obtainable before the start. Livingstone had at the end of the first three miles taken in about fifty yards of the concession given to Smith. He then appeared very “soft”, and not in a condition for the long journey. At the end of the fourth mile, the Paisley man had recovered his lost ground, and thereafter Livingstone never had a chance, and was distanced so rapidly that, at the conclusion of the eighth mile, Smith had nearly placed a lap between them. At the finish of another lap, Smith passed Livingstone (Smith 8 ½ miles, Livingstone 8 ¼ miles), the former going as strong as a lion, while the latter was about used up. They travelled in company until Livingstone had concluded his ninth mile (Smith 9 ¼ miles) when he called a halt, having run so far in 49 mins. 5 secs. Smith continued his journey alone, and, moving along in his own peculiar style at a rare speed, finished the ten miles with a magnificent spurt, and apparently not the least distressed, in the very good time of 53 mins. 11 ¾ secs., which, considering the ground was in a very bad condition after the thunderstorm, is a remarkably clever performance. His time for the full distance would be about 5 secs. under 54 mins.” Given the circumstances, it was an astonishing achievement.

On 13 October Smith returned to Shawfield to compete in a 10-mile handicap for a total purse of £20. He faced, among others, against Livingstone and Paddy Cannon from Stirling, a rising force in Scottish pedestrianism. 3,000 spectators turned out to watch the action. Livingstone was virtual scratch with a start of 300 yards, then Smith at 400 yards and Cannon at 440 yards. The following report appeared in Sporting Life: “A good start was effected, McCallum, the limit man, showing the way for a mile and a half, when Muir went to the front, closely followed by Newton. McCallum dropped off after completing three miles and a quarter, and at this juncture Newton took first position, which he kept till five miles and a quarter had been traversed, when Cannon rushed past him, Newton retiring at five miles and a half, leaving Smith in second place. On coming up the straight for six miles Smith spurted, and wrested premier position from Cannon, amidst cheers by the onlookers. This place he kept, and at eight miles then men were running in the following order: – Smith, Cannon, Livingstone, Gardner, and Evans, the others having dropped off. Smith, running in splendid form, continued to improve his position, and at the finish came up the straight in grand style, and looking full of running, 100 yards in front of Cannon, second, Livingstone, about 700 yards behind, being third; Gardner, fourth, a good distance behind Livingstone, and Evans fifth. Time of the winner (off 400 yards), 52 min. 15 sec.” A rough calculation suggests Smith would have gone the full 10 miles in about 53:30, which would have been just outside his lifetime best. It was as if he had rolled back the years. Cannon would also have gone under 54 minutes had he completed the full distance.

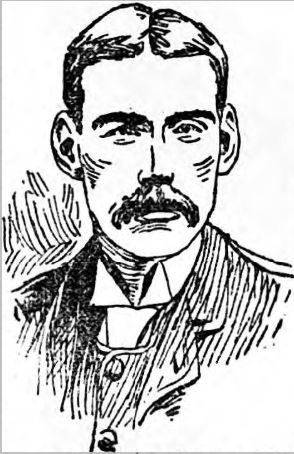

Cannon and Smith appear to have established a working relationship, with Smith acting as the trainer and advisor. Smith’s vast experience on and off the track would have been very valuable to Cannon, who derived his fitness from hard manual labour on a farm near Stirling and the occasional training spin. In 1888, under the guidance of Smith, Cannon would set outright world records for 3 and 4 miles of 14:19.5 and 19:25.2 respectively.

Paddy Cannon was a protégé of Cutty Smith

This sums up the most important years in Cutty Smith’s long career as a professional runner. After 1883 his performances would gradually decline, but nonetheless he continued to enjoy considerable success at the Highland Games until the early 1900s, when he was well over 50 years old. After his golden years as a runner were over, Smith, it appears, returned to his old profession of card cutting. Together with his winnings at the Highland Games and his coaching work, he was able to keep his head above water. In 1891 he was living with his parents and his three daughters at 2 Phillip Street in Paisley. Ten years later, he was still living at the same address with two of his daughters and a boarder, a Mrs. Muir, at fruit preserve maker. He himself had become a widower in 1886 when his wife died from the effects of an abscess. During his sporting career Smith had been a prolific competitor, winning countless handicaps on the rough and ready grass tracks at Highland Games meetings throughout the country. But the true measure of an athlete’s greatness is the mark he leaves in the history books. Among his greatest triumphs were the Scottish 10-mile championship in 1870 and 1878, the winning of a silver mile challenge cup in 1877, the British six-mile and ten-mile championships in 1878 and the winning of a handsome championship belt in a six-day race at Aberdeen in 1879. Needless to say, he set a few records along the way: two Scottish records over ten miles and a “world record” for 25 miles eighteen years before the “Marathon” race was conceived. He also coached and dispensed his advice to an indeterminate number of other runners, most notably Paddy Cannon, whom he guided to long-standing world records for three miles and four miles in 1888.

On the evening of 7 December 1907 Smith left his two daughters at home and went out, perhaps for a few drinks in the pub. But he did not return and was reported missing by his daughters. All attempts to find him were unsuccessful. A few weeks later his body was found washed up on the banks of the River Cart, about 400 metres from Barnsford Bridge near Inchinnan. What had happened? Had he stumbled and fallen into the river and perished in the icy water? Had he been inebriated? There was no evidence of foul play, and a coroner’s inquiry returned a verdict of death by “supposed drowning”. He was 60 years old.

Smith’s best performances

| 1 mile |

4:34.4e |

Gateshead | 30 September 1872 |

| 2 miles | 9:52.0+ | Glasgow | 8 June 1878 |

| 3 miles | 15:10.0+ | Glasgow | 8 June 1878 |

| 4 miles | 20:35.0+ | Glasgow | 8 June 1878 |

| 5 miles | 26:03.5+ | Glasgow | 13 May 1878 |

| 6 miles | 31:29.25 | Glasgow | 13 May 1878 |

| 10 miles | 53:22.0 | London | 26 December 1876 |

| 1 hour | 10M 598y (16640m) | Sittingbourne | 16 February 1878 |

| 20 miles | 2:10:00+ | London | July 15, 1878 |

| 25 miles | 2:50:22+ | London | 15 July 1878 |

Thanks to Peter Lovesey for stats and Mark Aston at the ILHC.

Note: Alex Wilson who wrote the above profile of Cutty Smith has also contributed many other very good accounts of runners, their life and times, to the website. All well worth reading they include Paddy Cannon, Robert McKinstray, Frank Clark, Alex Haddow, Alex Duncan, John McGough, PJ Allwell and J Wilson. All written to the same high standard, all with fascinating illustrations, just click on the names to be taken to the individual items.