Scottish distance running 100 years ago: Flashback to the year that was 1922

Alex Wilson

Today, in 2022, Scottish distance running has arguably never been stronger at the elite level, with Laura Muir and Josh Kerr winning silver and bronze respectively in the 1500 metres at last year’s Tokyo Olympics. We presently have what you might call an embarrassment of riches, with the likes of Josh Kerr, Neil Gourley, Jake Wightman, Andy Butchart and Callum Hawkins leading the way on the men’s side, and Laura Muir, Jemma Reekie and Eilish McColgan on the women’s side. Not only that, we have a number of very good athletes “waiting in the wings”, as it were. This year we can look forward to a World Championships, a European Championships and a Commonwealth Games. It remains to be seen how our athletes will fare, but the prospects are looking good.

How was the situation 100 years ago in 1922? Things were very different then. There were no major international track and field championships. 1922 was right in the middle of the quadrennial Olympic cycle. The first Commonwealth (British Empire) Games were eight years away. The first European Championships were 12 years in the offing. The first World Student Games were however just around the corner and would be held in Paris in May of 1923.

The war had been over for just over three years. The athletics scene had quickly returned to some semblance of normality after the cessation of hostilities. Fortunately for athletics, it was a cheap sport. Money was tight, owing to a stagnating British economy, sky-high unemployment and drastic austerity measures. In the period after the war, the clubs again saw their membership increase. However, many clubs still lacked the financial resources to promote a meeting. However, the situation improved from 1922 onwards, as reflected in the performances of UK athletes and increased strength in depth.

In 1922 the presidency of the S.A.A.A. passed into the safe hands of William Struthers, the energetic driving force behind the success of the Greenock Glenpark Harriers. This was the man they needed at the helm of Scottish Athletics, a man who knew how to generate revenue from his experience as a meeting promoter.

The S.A.A.A. championships were held in Edinburgh at Powderhall Grounds, where local student Eric Liddell wowed the home crowd by winning both short sprints and leading the E.U.A.C. relay team to victory in the one-mile relay race. Duncan McPhee of the West of Scotland Harriers wasn’t to be outdone, though, also pulling off the difficult half-mile / mile double. Officials were in such a quandary over who was the most meritorious performer that they awarded the Crabbie Cup jointly to McPhee and Liddell. It is also worth noting that heavy eventer Tom Nicholson lived up to expectations by adding another three gold medals to his trophy cabinet.

In 1922, for the first time since 1914, Scotland hosted the Triangular International Contest against England and Ireland at Hampden Park. However, the Scots were unable to repeat their 1921 victory, with England fielding a stellar team and running away with most of the points.

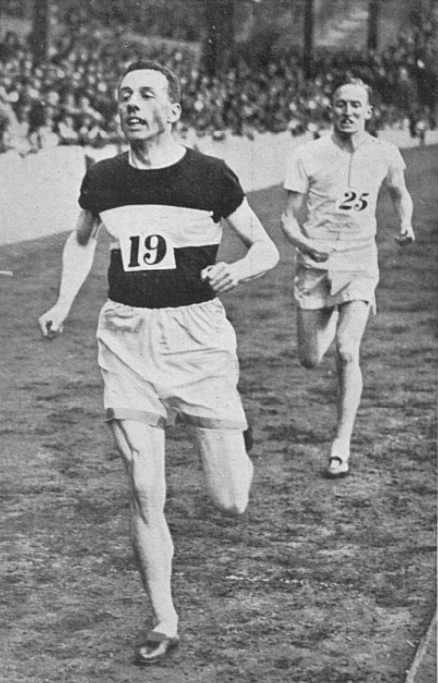

The star of Scottish middle-distance running, Duncan McPhee, still shone brightly in 1922. This veteran of pre-war athletics, a 1500 metres finalist in the 1920 Olympics in Antwerp, was still going strong. He had little reason to retire: he still had the measure of his compatriots in the half-mile and in the mile. Approaching thirty, McPhee was arguably stronger over the mile these days. With double Olympic gold medallist Albert Hill having hung up his spikes for good, the A.A.A. mile championship at Stamford Bridge was wide open that year. It had been 11 years since the last Scot, the late Douglas McNicol, had accomplished the feat of winning. Before that, you’d have to go all the way back to 1899 when the phenomenal Hugh Welsh won the A.A.A. title for the second time in succession. The mile was the blue ribband event of the A.A.A. championships and the race everyone wanted to win. Famed Bellahouston postman John McGough had thrown his hat into the ring several times in the early 1900s but had failed to advance beyond a runner-up medal, finishing in that position three times in succession, in 1904, 1905 and 1906. In the end, experience told, McPhee timing his sprint perfectly to win by three yards over emerging middle-distance prospect Henry Stallard in 4:27.4.

Duncan McPhee (W.S.H.) winning the 1922 AAA mile championship from Henry Stallard

McPhee had arguably been pushed harder in the S.A.A.A. mile championship, where he had to pull out all the stops to win by a bare yard from E.U.A.C.’s Charles Brown in 4:31.2. He only ran faster that year on one occasion, and that was in the mile at the Rangers Sports at Ibrox, which he won in 4:23.8. This was close to his pre-war lifetime best of 4:22.7, set when finishing third in the 1914 A.A.A. mile championship.

The Old Firm athletics meetings were back in full swing and as popular as ever, with the event at Ibrox attracting 20,000 spectators. The Celtic FC event a week later attracted slightly fewer spectators (15,000), due to the vagaries of the Scottish weather. Scottish mile champion Duncan McPhee took part in both events, winning the open mile handicap at Ibrox in 4:23.8 and the half mile handicap at Celtic Park in 1:58.0 from 6 yards. He also finished second in the open mile at Celtic Park in 4:28.0 from scratch.

How did the individual distance events shape up in 1922?

Women’s athletics was in its infancy at the time, and there were no female middle-distance performances of note in Scotland, so the focus is, by necessity, exclusively on the men.

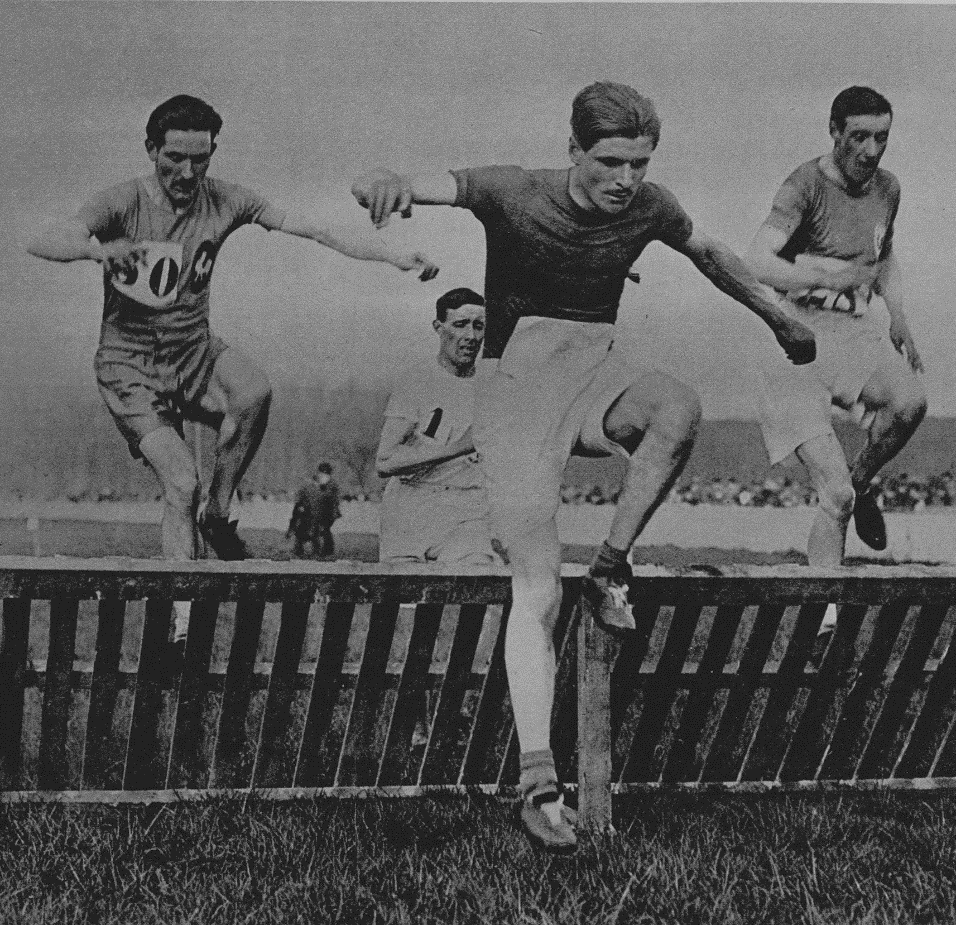

The fastest time run in Great Britain over the half mile in 1922 was 1:55.6, set by Edgar Mountain at the A.A.A. Championships, where he won by a hair’s breadth from Welshman Cecil Griffiths. Fastest Scot was McPhee who was a distant fourth in the A.A.A. race in 2:00. The next fastest was William Rankine Milligan of O.U.A.C., later Lord Milligan, M.P. for Edinburgh North, who finished second to Edgar Mountain in 2:02.4 in the annual Varsity Match at the Queen’s Club in London. The bespectacled Milligan was a prodigiously talented half-miler. He had run 1:57.4 in New York the year before on the back of light training but, for academic reasons, competed sparingly that year. Behind them the field was thin and the standard poor. Charles Mein, runner-up in the S.A.A.A. Championships in 2:04, and Charles Brown, Scottish Universities champion in 2:04.4, were the only other Scots who bettered 2 minutes 5 seconds that year.

O.U.A.C. half-mile specialist William Milligan in action

The fastest Briton in the year over the mile was Henry Stallard of Cambridge University, who made the distance in 4:21.0 at Cambridge on March 9. He also won the Varsity mile in 4:22.4. Stallard would have been the undisputed No. 1 in Britain that year had it not been for our own Duncan McPhee, who showed him a clear pair of heels at the A.A.A. Championships. Behind McPhee there were several performances of note, both north and south of the border. 1922 Scottish Universities Champion Charles Brown posted a 4:31.4 on the slow track at Craiglockhart on May 27, so his performance at the S.A.A.A. championships should not have come as a surprise. C.U.A.C.’s William Seagrove, silver medallist in the 3000-metre team race at the Antwerp Olympics two years earlier, turned out only once over the mile. And that was in Cambridge on March 9 where he negotiated the distance in about 4 min 33 seconds. His speciality was of course the 3 miles. Scotland’s other Blue, William Milligan, also got his name on the board in 1922, posting a 4:33.9 at Oxford on March 3. No other Scots managed to better 4 minutes 40 seconds.

Now to the 3 miles. Here one would also have to consider the international equivalent, the 5000 metres, and the (then standard) 4 miles as well. Joe Blewitt of Birchfield Harriers produced arguably the best individual performance by a Briton in 1922 when he clocked 15:15.2 over 5000 metres at Paris on October 8. He was also best Briton over 4 miles at the A.A.A. Championships where he finished second behind the “invincible” flying Finn Paavo Nurmi in 20:04.0. In terms of times, however, Scotland’s own William Seagrove was almost on a par with the Birchfield runner. Seagrove made only two appearances over 3 miles, but they were quite something. On March 11, he ran 14:50.0 at the Fenner’s ground in Cambridge, the fastest time over that distance in the UK that year. A fortnight later, he won the Varsity race by the length of the straight in 15:02.6. The S.A.A.A. four miles title went to Jimmy McIntyre (Shettleston Harriers), who finished 10 yards ahead of Frank Watt (E.U.A.C.) in 21:00.8. The Universities Championship was secured by Charles Johnston (G.U.A.C.) who won at Aberdeen on June 17 ahead of James Hill Motion (E.U.A.C.) in 16:01.8. Motion, however, accomplished the third fastest time over 3 miles by a Scot that year, when he completed the distance in 15:18.8 at Craiglockhart on May 20. Otherwise, there were no performances of note, except perhaps a rare track appearance by 39-year-old George Wallach, Greenock Glenpark Harriers, who ran the four miles in Manchester on June 10 in 21:35.0. Although he missed five of his best years because of the war, Wallach could look back on a long and distinguished career, capped by a runner-up finish at the 1914 International Cross-Country Championships.

C.U.A.C.’s William Seagrove was UK #1 over 3 miles in 1922

The last long-distance track championship in question in 1922 was the 10-mile race. In the three years from 1919, Scottish athletes had set the fastest times in the United Kingdom. Professional runner George McCrae posted scratch times of 53:32.0 and 53:16.0 in the “Marathon” race at Powderhall Ground in 1919 and 1921 respectively. McCrae also notched up a fast time of 53:23.8 in 1920, but this was bettered by Jimmy Wilson of Glenpark Harriers, who set a Scottish amateur record of 52:04.0 in winning the S.A.A.A. championship at Celtic Park. The situation in 1922 was less rosy, with no Wilson around to provide any cosmetics. The S.A.A.A. championship went to Jimmy McIntyre, who won at Celtic Park in a modest 54:59.0, good enough to see off future Scottish marathon star Duncan McLeod Wright, Shettleston Harriers, by over 300 yards. Little did we know that McIntyre would blossom into a world-beating cross country runner within the space of a year. It was not until the following year that “Dunky” made a not so auspicious marathon debut in Aberdeen. In all, eight men broke the hour for the 10 miles that year, which was a marked improvement in terms of strength in depth. The A.A.A. title went to Derby veteran Halland Britton in 53:24.2, but the fastest time in the United Kingdom was again claimed by a professional – Bob Cole of Hereford – who won the “Powderhall Marathon” on January 2 in 53:17.0.

Jimmy McIntyre (Shettleston Harriers) is seen here on the right of picture

That just leaves the cross-country and, of course, the International Cross-Country Championship. In 1922 the event was held at Hampden Park in Glasgow, where the S.C.C.U. played hosted to five nations: England France, Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The win went to the great Frenchman Joseph Guillemot, who led France to the team championship. The Scottish team acquitted themselves admirably, packing well to take third. Despite being in his 40th year, George Wallach proved age is no barrier by rolling back the years and finishing an astounding fourth in the individual race.

In 1922 George Wallach proved that age is no barrier by running fourth in the International Cross-Country Championship

So that was the year that was 1922 from the standpoint of Scottish middle and long-distance running. It was one of those watershed years with several torch bearers, amateur and professional like, in the twilight of their careers and not a lot of strength in depth. However, the harrier scene was alive and kicking, with the likes of John Suttie Smith, Frankie Stevenson, Walter Calderwood, Robbie Sutherland, Jimmy Wood and Tom Riddell coming through the junior ranks. And Dunky Wright had yet to find his true calling.