John Emmet Farrell is a legendary figure in Scottish athletics. A member of Maryhill Harriers from the 1930’s right through to the 21st century, he won Scottish titles and international recognition on the track, over the country and on the roads. He won medals in all age groups from Senior Man right through all the veterans age groups and made friends wherever he went. Loved and respected, he represented all this best in athletics, and more important, all that is best in the people of his chosen sport and the people of Scotland more generally. He wrote his autobiography in 1993 but it was published in such small numbers that very few have managed to get their hands on a copy, and those with a copy are afraid to let it out of their hands. The intention is to reprint it here available for all who would like to read it. Part athletics autobiography and memoir, it is also part social history and part hhis own philosophy. It was called

THE UNIVERSE IS MINE

The adventures, thoughts, humour and reflections of a unique Cross-Country Champion!

INTRODUCTION

Because I’ve been running for over fifty years, a golden celebration if you like, quite a few people have suggested that I write a “Running Commentary” from my debut in 1933 up to the present. But it was David Peat who was responsible for filming the feature on my colleague Gordon Porteous and myself as veterans running in the Glasgow Marathon, in Television’s Channel 4, who really encouraged me to do just that. Perhaps they are surprised at such a long attachment to one sport, but I am not unique in that respect as several of my veteran colleagues have an equal recordd. It has been suggested that we are bigamists, being married to our hobby as well as to our wives. But of course they are only being facetious, as most of the wives are very supportive, realising that if we are out running we are not gallivanting to the pub.

In should not like what I write to be considered anything like an autobiography; that would be somewhat egotistical, though as some people have had ghost-written biographies written in their twenties, at well over three score years and ten I can be forgiven on the score of age. Rather I should call it a trip down memory lane, almost a soliloquy if you like, as despite the vicissitudes of life I am amazed at my length devotion to running. Because I was something of a dilettante in sport: swimming, football, wrestling and a little boxing claimed my attention at different times. I tended to be a true geminian in other activities also, always wishing to stretch myself and cross new frontiers without consolidating any gains. Considered a natural athlete I inclined to discard each in turn before reaching a level of proficiency except n the case of swimming where coached and encouraged by my father I won several honours.

Running has proved to be an exception and because of that it is not so much my career as an athlete, the races won and the races lost but the attraction of running itself that I wish to high-light. How basic in some respects so prosaic and pedestrian, yet from initial commonplace strands it can be woven into a tapestry of beauty and culture involving recreation therapy, fellowship, exhilaration, freedom and the magical beauty of nature. As I write I should like to emphasise that my story is mainly subjective and perhaps a bit parochial concerning my early days when in my prime, though I have added some later experiences as a veteran runner. In addition I must apologise for not mentioning many of the runners I met and knew in those far-off days and those of the present and immediate past whose talents I admire so much. If I did so, my story would become a catalogue and if I mentioned some, others equally brilliant would be left out and that would be unfair. So if I do refer to athletes some well-known andd others not so well-known it is to illustrate a point according o the windmills of my mind. I am prepared to sacrifice rigidity rather than spontaneity.

In addition after 50 years the memory becomes a bit rusty except perhaps for specific high-lights, and I am indebted to copies of “The Scots Athlete” and “The International Athlete” edited by my friend and colleague WJ Ross for which I wrote a monthly article under “Running Commentary” which was well received round the world of athletics for much data.

As post-script to this introduction, the title “The Universe Is Mine” is revealed at the end of the text.

EARLY BACKGROUND INFLUENCES

Though I joined my club Maryhill Harriers in the autumn of 1933, so long ago, memory telescopes time and it seems like yesterday. Even so, my early athletic background may have unconsciously provided a spring board for what seemed at the time an accidental event. Born in Balham Grove, London, in 1909, my parents came to Glasgow when I was a few months old and I regard myself as a Glaswegian, having been here ever since. Actually my father was born in Dundee and my mother in Hamilton but their sojourn in London was due to the former’s job which involved a roving commission.

He was almost a semi-invalid in his youth and far from robust but by dint of a strict physical culture regime progressed to such an extent that he eventually won the Eugene Sandow medal for excellence in his weight class, around 9 stone. Sandow was one of the outstanding men of his day.

Though not a strict vegetarian, I have a leaning towards it so it was with a touch of humour that I later heard my grandfather and his family were big meat eaters and when they left the district the butcher broke down and wept. Most of my immediate ancestors were not long livers but I could never get corroboration of my mother’s antecedents, the Balfours way back from farming stock in the East of Scotland. That they were so healthy and lived so long that they had to shoot some of them as the undertaker threatened to leave because of lack of business.

Returning to the factual, my dad taught swimming and used to jump off the high board with me on his back which, of course, entailed complete immersion. The result was that at five years old, water had no fears for me. Just as I was learning to swim, my father volunteered in the first world was, the so-called war to end war. Every tramcar had a poster of Lord Kitchener with finger pointing and the caption “Your Country Needs You”; and the newspapers were full of articles denouncing the Kaiser. Typically war hysteria was rampant. My father was invalided out before hostilities ended with kidney trouble and disillusioned with the stupidity and tragedy of war.

Under his guidance, I became an excellent swimmer winning my first race, the learner’s 25 yards with the dog’s paddle stroke easily out-pacing the orthodox beast-strokers. From there I graduated to the crawl stroke where eventually I won the Junior championship of my club Maryhill Victoria and later, while still a Junior, the Senior championship over 300 yards despite the attempt to bar me from the latter race because of my age. Little did I know that I was later to win the Maryhill club championship for cross-country running! Later at 16 I was close runner-up in the Western District long distance championship over one and a half miles in the sea at Troon and at 19 was again second in that event won by Willie Burns, who was later to swim fro Britain in the Olympic Games. Earlier I had won the Under 14 schools championship of Glasgow over 75 yards.

Sometimes my father took me out running for two or three miles for extra stamina.

THE DEBT I OWE

I mention these facts because anything I ever achieved as an athlete and a runner was in large measure due to that background and encouragement. He instilled in me a desire for fitness and exhilaration, a birth-right for which I am forever grateful. Sometimes I muse about these early days, in some ways so simple and uncomplicated and contrast them with modern times where in technological terms we have advanced so much.

Then single-ends were common, a room and kitchen house was standard with scullery adjoining, not a full-fledged kitchen, no baths, communal toilets, gas lighting, no radios or television. When a motor car appeared for the first time in our street, people crowded round it as if it were something from ‘Outer Space’; even aeroplanes were rarely seen. Children took up the cry of ‘an aeroplane’ when one appeared in the sky and any idea of going to the moon was a Wellsian fantasy. We have gained so much in hygiene and comforts but have paid a price in other respects. We live with pressures at every level which are conducive to nervous disorders and those which follow comparative affluence replace malnutrition and infectious diseases. It is doubtful if the quality of life has improved.

Our ingenuity is in advance of our wisdom. Many examples abound and to discuss these a whole essay would be required. Suffice to stress how important is an activity which is recreational and therapeutic in these modern times. I believe that athletics and especially running fits that bill and it is my desire to promote and stress the importance of the aspect.

TAILTEANN GAMES AND A GUINNESS RECORD?

In 1928 I was selected for Scotland in the Tailteann Games (The Irish Olympic Games) in Dublin. This event was even older than our Olympic Games, going back into the mists of time. To be selected one had to have some Irish ancestry, but it was very loose going back to second or third generations. I swam in two events, the 800 and 1500 metres but could do no better than fifth place in events which the Canadian and Australian swimmers dominated. Still it was a great experience. A week in Dublin meeting these great swimmers competitively and socially and the Irish authorities were great hosts.

Among the high-lights was a visit to the Guinness Stout Works and I was impressed with the hygiene and high standard of the various processes. Perhaps it’s much too late to apply for inclusion in the Guinness Book of Records for something that happened so many years ago but I often wonder if any other person has had the experience of being drunk for just 9 seconds (I believe I just beat the count of ten). We had to negotiate a bridge over one of the plant processes, a vat containing a frothing mass of Guinness. Asked by the conductor to take a deep breath of the fumes, I must have inhaled too deeply and staggered off the gangway but thankfully soon regained my equilibrium. I still recall our manager with a tankard of foaming Guinness and lobster sandwiches in the refreshment room later. We swimmers had to do with soft drinks.

Sadly, shortly after, the Tailteann Games became defunct whether due to lack of interest or lack of funds I cannot say. The loss of any colourful tradition leaves the world a drabber place.

PERIOD OF STRUGGLE

Later in the year my father died. It was a sad occasion not helped by the fact that my mother did not get a widow’s pension because my father did not have enough insurance stamps. He had gone into the clothing business in a small way and many of his customers were miners. But the miners’ and general strike of 1926 proved a personal disaster for his business as the miners with whom he had a great affinity were unable to pay and his business failed. That, added to his health deterioration, due to the war, was something from which he never recovered.

BRIEF ENCOUNTER

I had struggled to attend Glasgow University, taking classes and trying to do a part time job. But despite the help of some of my colleagues who provided me with missing lectures the strain proved too much and I had to leave. In those days no financial provision was offered only payment of matriculation fees. I took classes in English Literature, Modern Languages (French and Italian) and Moral Philosophy. But no experience is entirely lost. I was particularly indebted to Professor McNeile Dixon who imbued in me a love of English Language for which I felt I had a natural aptitude.

THE WIT OF GK CHESTERTON.

At one of the lectures, that well-known man of letters and Master of Paradox GK Chesterton was a guest speaker. The students, an unruly lot, gave him a pretty rough ride. Chesterton, a rather large gargantuan chap rejoined, “please do not cast your pearls of with against this one solitary swine.” From then he had them eating out of his hands.

Then it was back to the dole, the means test and casual labour. There was no cushion then against the misfortune of unemployment, yet in our own way we were reasonably happy. We hiked, played football, sometimes with paper balls, camped, swam in the lochs, yes even canals and rivers and as I said earlier, because of our mor basic life-style there were less passive entertainments and amusements. More debates and discussions; life was not so impersonal and despite much deprivation and more primitive living conditions, murder, assaults and vandalism were rarer events. The former had newsboys in the street shouting and people rushing down to read all about it.

What has this to do with athletics, one may ask? The temptation to watch the television does not encourage exercise or activity, physical or mental. Neither does the car, the elevator or the business lunch. Still there are signs of reaction against the softer aspects of our present civilisation.

Indoor facilities for a variety of sporting activities are present and the cult of the marathon, though perhaps constituting a hazard for the untrained or semi-trained represents a challenge and a deep almost primitve urge to play the spartan.

GONE TO SEED

To some extent having always been an athlete I felt at this time I had gone to seed but this was not strictly so. Most weekends were spent camping at Milngavie and Loch Lomondside. Among my companions was a Maryhill lad Robert Grieve, a great lover of hills and mountains, later better known as Professor or Sir Robert Grieve, a former chairman of the Highlands Development Board and lecturer on town planning.

On one occasion we decided to camp on one side of the islands on Loch Lomond. Two of us could not manage till evening so the rest of the party said they would light a fire to direct us to our particular island as we rowed out in the darkness. Unfortunately they retired to their sleeping bags rather early and the fires went out leaving only embers. It was a rather scary experience rowing in the pitch black darkness trying to reach our particular island. Proficient swimmers, we were both more than relieved to find sanctuary. There are better places to find oneself than in the icy waters of Loch Lomond on a Saturday night. We finally got settled and drummed up; a sleeping bag short, two of us had to share one. The constant turning over of each partner was not conducive to pleasant dreams.

FUN AND GAMES AT THE LOCH

However, next morning was another day and a glorious sunrise wakened us. I recalled Shakespeare’s words from Romeo and Juliet,

“What envious streaks do lace the severing clouds,

Night candles are burt out and jocund day stands,

tip-top on the misty mountain tops.”

They were appreciated but less so than the tea and hefty sandwiches which we exchanged with each other according to taste. All except one of our crowd who kept his own sandwiches to himself and put them discreetly out of reach. Unfortunately they weren’t out of reach on a hungry wandering sheep who devoured half of them. We couldn’t help laughing. It was then I discovered a mildly sadistic trait in my character.

GIANTS OF SPORT

As I have earlier indicated, before I fell in love with running I flirted with various sports. After swimming, football, boxing and finally wrestling. In fact in the latter I managed to reach the semi-final of the Western District Championship but was beaten on points by the eventual winner of the 10 stone division. Natural flair without technique is not enough.

That period was rich in colourful sporting personalities. babe Ruth “The King of Swat” as he was called, the great baseball player was at his peak. The highest paid athlete of his time, his career seemed in ruins when he put on excessive weight through easy living, but through will-power and spartan regime he made a come-back to become once more the darling of the American sporting public. Jack Dempsey, “The Manassa Mauler”, arguably the greatest heavy-weight of all time was the sensation of the 1920’s. Many remember his fight with Gene Tunney the well conditioned young orthodox boxer who clearly out-pointed Dempsey despite being knocked down in the long count. Dempsey’s reluctance to go to a neutral corner meant that the count did not start until he did so and thus Tunney was given several seconds extra respite to get to his feet.

But this was the Dempsey of 1927 who had tasted success and easier living that accrues, not the perfect specimen of 1919, the spartan hobo who demolished in turn the giant Jesse Willard, the scientific genius Gerges Carpentier and Firpo, the powerful giant of the Argentine. Carpentier hit Dempsey with his Sunday punch that had knocked out British boxers Joe Becket and Bombardier Wells in one round but the latter merely shook his head and the former realised that defeat would be his portion. It lasted just three or four rounds. The fight with Firpo is reckoned to be the most sensational and primitive fight ever witnessed. Firpo knocked Dempsey clean out of the ring in the early rounds. Pushed back in, Dempsey floored Firpo four times before the referee stopped the fight.

It has to be said that professional boxing is a rather primitive affair and the consensus of modern medical opinion is highly critical and in terms of logic one has to agree with their findings. But one still has to admire the perfection of Dempsey’s physique and his lightning reactions. Not a behemoth like some of today’s heavy-weights, he stood 6 ft 1 in and weighed just over thirteen and a half stone. It is not the boxing but the training that they do that makes them such perfect physical specimens.

JOHNNY WEISMULLER OLYMPIC CHAMPION AND FILM TARZAN

Johnny Weismuller, Olympic swimming champion, became the most famous Tarzan of the series. The called him “the fish that walked like a man”. His speciality was the 100 metres sprint but after winning that Olympic event he had a classic confrontation with the famous Swede Ane Borg and Australian ‘Boy’ Charlton. The former was double jointed and the latter was some boy standing well ober six feet and weighing nearly fifteen stone. The 400 metres was well over Weismuller’s best distance and below that of the other two who were 1500 metres specialists. Weismuller won by the touch absolutely exhausted, the others had plenty left but could not quite match the former’s speedy finish.

A report is told of how in a brawling water-polo match Borg had several teeth knocked out. Angry he turned out in the 1500 metres and broke the world record. There are several stories told of Weismuller. One that has been vouched for is the time he sat with officials at dinner after a swimming meet. JH Howcroft the well-known coach and official sitting next to Weismuller turned to an official to say a few words and when he returned his dinner was gone… Johnny had eaten his own dinner and Howcroft’s. Swimmers are certainly first-rate trenchermen.

I saw Eric Liddell and Paavo Nurmi run at Ibrox. In fact I spoke to the latter as he left the stadium; but he spoke little English and his companion replied on his behalf. Nurmi nodded and smiled. He seemed a very pleasant fellow.

THE GENTLE GIANT

The great Russian wrestler George Hacken smidt made a guest appearance at the Glasgow Hippodrome about 1932. Only about 5 ft 9 in tall he looked just like a business executive but when he took his coat off his physique was impressive. It is said that on one occasion he was set upon by three men in London intent on robbery. He gripped one assailant, held him aloft and gently put him back on his feet. He made off and the other two followed suit. They did not wait to be introduced. A gentle giant indeed.

What pop stars are to the present generation the sporting greats were to ours. I remember passing a shop in Sauchiehall Street and seeing a copy of the sporting magazine ‘Superman’ with a frontispiece of the ‘Greek Adonis’, Jim Londos, the great all-in wrestler. In my anxiety to get a copy I nearly bowled over two business gents with brolly and brief-case, an unpardonable display of indecorum!

MARYHILL MEMORIES

In those days, Maryhill was a colourful district. It had what was called atmosphere. The Forth and Clyde Canal wended its way round our district pat the home of Partick Thistle Football Club affectionately known as the ‘Jags’. Cruise boats with romantic names such as the Gypsy Queen, the May Queen and the Fairy Queen carried passengers on a fascinating journey from the Clyde to Kirkintilloch and as they passed our canal bridge hooted their sirens to attract the attention of “Jock the Briggie” who lived in an adjoining canal house. This worthy raised the bridge by hand levers to let the boats go by. School children, of which I was one, appeared as if by magic to run on the bank alongside and were rewarded with pennies thrown out by the passengers. Then ensued what ws known as a ‘scramble’ , a melee often duplicated at weddings.

Earlier as youngsters, not having the sophisticated games and toys of the moderns, we spent our energies on rather robust games called ‘release’ which employed a lot of running and hunch-cuddy-hunch in which teams of 4 or 5 took turns to jump on each others crouched backs. It was not surprising that most of us were fit and active despite, or perhaphs because of our basic life-style and lack of amenities.

AMATEUR RULE BROKEN?

On one occasion about six of us boys decided to have a race around Murano Street and Benview Street, next to the local Ruchill Park. Six times round was agreed, making it around three miles. Each of us put a farthing into the kitty a considerable amount of money in those days when an ice-cream wafer cost ne penny and a fish supper cost four pence. When coal went up from 1/11 to 2/1 a bag there were angry scenes and house wives shook their fists at the merchant. As the Will Fyfe song went – whisky was tweve and a tanner a bottle. I managed to win the race with a boy called John Gemmell second, but “Jock the Briggie’s” son, Jimmy Young who held the bets dropped out and went to ‘Gerties’ the local sweet shop with the proceeds. He later pleaded that his glycogen store had run out but rendered it in the vernacular “I was knackered” he said. He offered me a pencil as a consolation. The pencil was blunt, symbolically appropriate as I wasn’t very shrp on that occasion.

I sometimes wonder whether ethically I had broken amateur rules and become a professional by runing for money for the large sum of around two pence. But then at 12 or 13 years old I might be considered under age and in the event did not receive any money although the intent was there.

PROFESSIONALISM, YESTERDAY AND TODAY

The above incident may appear somehwat humorous and even trivial but the examples I am about to quote though fairly insignificant were quite serious for the individuals concerned. Many years ago James Fleming of Motherwell was banned from running in the National Novice cross-country championship because he had won a tie in an army race. Jimmy Fleming later went on to win national honours on the track and over the country. Bobby Reid from Ayrshire had briefly played a few games in junior football receiving just nominal expenses. That made him a professional. He was later re-instated as an amateur winning the Scottish cross-country title and later became one of the stalwarts of Birchfield Harriers finishing close runner-up to Jack Holden in the English National. But he could not be considered for international selection where the amateur ruling was more strict.

THE GHOST RUNNER.

Perhaps the most publicised example of the injustice of this strict amateur ruling was the case of John Tarrant who as a teenager boxed briefly for a very small amount of money, was declared a professional as a runner and ineligible to compete in amateur competition at any level. He came to love running and ran in races unofficially and without sanction, with no opportunity of winning a prize or recognition. Hence he became known as “The Ghost Runner”. Surely that demonstrated the real amateur spirit. By dint of perseverance and support by athletes and others who admired his spirit and talent John Tarrant was at last re-instated and went on to win many races and set world records over various long distances. But he also, because of the stringent rules could never earn recognition at International level.

NURMI BANNED AT THE OLYMPICS

At an even higher level there is the case of Paavo Nurmi hero of the Paris and Amsterdam Olympics who was banned from running the marathon in 1932 in Los Angeles because he had received expenses which were considered too liberal. By virtue of his class and his almost robot machine-like pace he was considered to be a near certainty to win that event.

In that Olympic year, just before I joined Maryhill Harriers, I took a special interest in the proceedings, not only because the Games themselves but because two great Maryhill champions were involved. In the marathon Donald McNab Robertson of Maryhill was selected along with air force runner Sam Ferris. However Donald, sole support of his widowed mother was forced to drop out because he could not afford the loss of six weeks wages (they travelled by liner in those days). Club mate Duncan McLeod Wright substituted. It’s fair to say that Ferris 2nd and Wright 4th respectively ran the race of their lives. There was no broken time financial allowance in those days. So Donald was penalised for being a true amateur as the others mentioned were for being pseudo-professionals. Later the famous Swedish runners Gunder Haegg and Arne Andersson were to suffer the same fate.

NOW FOR THE AMATEUR-PROFESSIONAL OR THE PROFESSIONAL AMATEUR

Now with amateur rules relaxed and almost in a state of limbo, we have full-time athletes able to train and race abroad, entitled to advertise goods and allowed to put winnings or appearance money into a trust fund from which they may draw for training facilities. I may comment briefly later on the philosophy of this change; suffice to say at the moment that the labourer is worthy of his hire. In other words if the elite athlete draws the crowds and enhances the gate money and television coverage by virtue of his talent and dedication it would be cavalier to deny him his reward. In our acquisitive society market forces prevail. Could there be a price to pay?

THOSE WERE THE DAYS

Grass is green afar off. So goes the saying, and certainly nostalgia tends to select the brightest colours from the spectrum. The sub-conscious mind tends to hide the more unpleasant aspects of the past.

Yet in some respects it is a bit sad to see so many athletic galas disappear. The Rangers Sports Meeting at Ibrox Park was one of the highlights of the season. Crowds f fifty to sixty thousand watched the finest athletes from America, Finland, England, Scotland and many other places in invitation events. But the good average runner did not miss out. He was catered for in the handicap sprints, half-mile and mile. SAdded to that were the steeplechase and obstacle races and the 5-a-side football where among others Rangers and Celtic fought out many stirring battles. In other words it was essentially a gala affair. Again Chesterton’s dictum that a thing worth doing badly and well is equally relevant. To express oneself in any activity and find enjoyment was the main thing. Perhaps because the sport was less serious there was more fun and banter. ‘To miss the joy is to miss all.’

THE STARTER WASN’T LAUGHING

I prefer humour to wit. The latter is brittle and has a fine logical point to it. The former has a humanity about it, laughter with a touch of poignancy. Most serious people have a strong sense of humour. It is essential for therapeutic reasons in a world which despite its attractions is not utopian. Perhaps that is why we often remember and enjoy incidents that appear trivial.

Some years ago at one of the meetings, the starter and his assistants were getting the athletes on their marks in the open mile handicap. With as many as seventy to eighty runners in the field this was quite an onerous undertaking. At last everything in order the starter raised his gun to send them on their way. Suddenly an athlete rushed out of the tunnel with hand upraised to take up his specific place on the mark. Nervously the runners settled once more on their marks awaiting the gun. Again the same athlete held up his hand in appeal to once more hold up the proceedings. Taking off his wristlet watch he handed it over to a friend. Finally the starter managed to fire his pistol and set the field off on its 4-lap safari. Our man ran just one lap and dropped out. It caused a great laugh except for one man, the starter. His face registered not laughter but something akin to hysteria.

MY DEBT TO A SWEDE.

As I have indicated I tended to get interessted more and more in running to the exclusion of other sports though at this stage in 1932 I was not myself a runner. An Olympic year and with two Maryhill Harriers making the headlines strengthened my interest. Maryhill District had many running enthusiasts and Maryhill Harriers was one of the top clubs with athletes of the calibre of Duncan Wright, Donald Robertson and many others. Just to be a member of such a prominent club gave even the ordinary member a special status.

in Murano Street, Maryhill where I resided at the time, there must have been at least a dozen active athletes. One of these enthusiasts was a chap called Bill Stromberg. He was a refugee Swede and under the hysteria of the post-war era was ostracised by some under the impression that he was German, instead of one of the victims of war and the German occupation. He was one of our camping colleagues and often encouraged me to join the club. I resisted his blandishments for some time. Later he lectured me, then accused me of lack of spunk. Needled, I rose to the bait and accompanied him to the club. That was about October 1933 and if there’s anything harder for the novice than running five miles over fields, ploughs, barbed wire fences and gates it must be really severe. Suffice to say I was agreeably surprised by my initial effort. My breathing was excellent and I thought to myself, “This isn’t so tough.”

DELAYED ACTION

Little did I know what was to happen later. Joining a few of the lads for a night at the pictures we boarded a tramcar and had to go upstairs. Somehow I made heavy weather of it, the legs felt so heavy. But coming down stairs at our destination they seized up entirely and I had practically to be carried downstairs. Every picture tells a story. As I hobbled into the refuge of the picture house, no bystander could have imagined that I was a would-be athlete.

GRASS ROOTS CATERED FOR

In the early thirties running was well covered by the press, not only the elite athletes but also those at grass roots level, the ordinary club runner. Of course that was before the advent of television which tends to concentrate on the big athletics meets apart from of course the modern craze, the marathon which usually gets a good coverage. This was especially true in cross-country which I have always regarded the life-blood of the sport with its scenic natural atmosphere, its colourful mixture of grass path and woodland, a tonic to body mind and spirit.

The Daily Record and Daily Express reported not only championship and club races, but also inter-club and ordinary club runs. We had large pack runs in those days in this most amateur of sports. There were three packs to suit the grade and ability of runners, slow, medium and fast. Each pack was controlled by a pace and a whip. The former dictating the pace, and the latter easing the pace if any runner fell behind. The slows would start first, perhaps 5 minutes ahead. Then followed the mediums, and finally the fasts another 5 minutes behind. At a certain stage of the run the packs caught up with each other and ran together until perhaps about a mile to go when the chief whip would order silence and in a stentorian voice announce “Make for home!” Like greyhounds on the leash the response was instantaneous. Forty or ffty runners on the rampage all manoeuvring for position was a colourful but daunting sight. No prizes, just the lust of honest contest and the thrill of the chase. But there was one special bonus, the names of the first three runners in each pack were published along with the names of the pace and the whip in Monday’s Record and Express.

MEET DAVIE WILSON, THIRD IN THE SLOWS

I was proud to be a member of Maryhill Harriers and rather in awe of those chaps who could make a five mile run such an easy routine affair. I remember being introduced to Davie Wilson, “3rd in the slows” on Saturday. I was proud to meet him. Later as I gained promotion to the mediums and finally to the fast pack I again recalled the dictumn of GK Chesterton that any activity is not just for the elite but for everyone who wishes to express herself or himself in terms of enjoyment. Inter-club runs were perhaps even more enjoyable. Bigger packs, a change of scenery, a little competitive zest if required; hot showers if lucky and tea and sandwiches provided a grand finale to the day’s outing.

THE HOSPITALITY THAT WENT WRONG

Among the venues which proved attractive in those days was that of Monkland Hariers. It wasn’t just the pleasant trail but the very nice tea provided by the good offices of an official who was in the purvey and baking business. On one occasion our club Maryhill Harriers was very poorly represented; so when the fixture list provided another visit I rounded on my clubmates pleading with them to support the Monklands fixture. I painted a mouth watering picture of the hot pies, the sausage rolls, the cakes and sandwiches we would be offered after our run; and though the club could not offer 4 star accommodation that was no deterrent. Our men turned up in numbers. After a good run, a basic wash in the old-fashioned enamel baths, everyone was ready for the piece de resistance, a good old-fashioned nosh; for runners are second only to swimmers in their healthy appetites. Surprisingly there was no sign of tables being set. The runners became restive then apprehensive. I pleaded patience, a quality that can be sustained only for a certain time. Then came the anti-climax, the grim news that the bakery had suffered a shut down due to an electrical fault. The spartan fare offered us was no compensation for the delights promised. I was innocent of all this but I had organised and encouraged our lads to travel and like football managers, I carried the can. It was a long time before I felt inclined to try my powers of persuasion again.

IS RUNNING A RECREATION NOW?

One must marvelk at the talent and fitness of the modern elite athletes. Their standard aided and abetted by single minded motivation and dedication is awesome and now that amateur rules have been relaxed their status and financial rewards are phenomenal. But at that intense level is running a recreation?

Isn’t recreation something that ne does after doing something else? But if an athlete does nothing else, does it not become his work, his profession? Sponsorship is available for the top athlete to train and race in various countries. But the competition is intense and there can be pressures from the media; thus careers may tend to be shorter because of that. It is the intensity of training and the professional approach which depends as much on the science of the laboratory as that of the track and road causing athletics to reach saturation point? A world record and an Olympic medal are tough assignments and prized possessions. Money and status can follow and of course in our acquisitive society, material success and money are perhaps the top priorities.

TWO KINDS OF WEALTH

Yet I suggest that there are two kinds of wealth. Some twenty years ago the following passage appeared in “The International Athlete” from my pen and is I believe still worthy of consideration. I quote, “Quite recently it was reported that a fabulously wealthy Arab had ordered at great expense (reportedly £1,000,000) for personal use, one of the most up-to-date planes with every conceivable form of luxury and comfort. It must be an enjoyable experience to glide above the clouds at 500 miles per hour by day or by night and to cruise among the stars. Exhilarating indeed and given to few. By contrast the speed of a fit athlete at 8, 10or 12 miles per hour is ludicrously slow; and yet by comparison it is the plane rider who is earth-bound and it is the fit surging athlete who really can tread the milky way and rub shoulders with the stars! There is no substitute for the surge of fitness expressed in action, the inner joy, the exhilarating abandon. No mechanical device can replace the creative effort generated by the individual from his own bodily resources. Creative too because it must ne earned; and all the more appreciated because some apprenticeship is involved. Some painstaking preliminary drudgery, unavoidable weariness, a dark tunnel to negotiate and then the sky and the light.

The stage from caterpillar to butterfly achieved not by a miracle of nature, but painstakingly, laboriously and gradually. How to achieve such a state of fitness! To jog, trot, preferably in bare feet round the path, meadow or golf course and woodland. To extend distance gradually. To keep at it until running becomes easy and the surge of fitness is felt. It will come. It must come. Personal circumstances make plane-riding exclusive. The prize of fitness is exclusive only by choice. Ruth was told that a jar od gold lay at the rainbow’s end. She trudged and trudged but never found that crock of gold. But at night she slept peacefully with the bloom of health upon her cheek. Excuse me, I must re-read Emerson’s essay on compensation”.

If the elite athlete can briefly forget his ambitions he will realise that he has that exhilaration and will rejoice in it. The tyro may never reach that standard. He too can reach that condition of “being in the pink”. The disparity of standard is lessened by that common factor.

THE ONLY REAL AMATEURS

In the strictest sense of the word, animals are the only true amateurs. Man’s egotism precludes him from that select status. Nevertheless competitive sport is a harmless way of channelling that egotism. Yet if you watch a cat playing with a piece of string or ball; two dogs wrestling and running, the beauty of birds in flight; all are expressing their creaturehood out of the very joy of existence. No trophies to be won, no applause expected.

I have been chided perhaps rightly by a colleague for not accepting cross-country running as absolutely amateur. But only in the strictest academic sense as I have mentioned above. In the pragmatic sense it is completely amateur. Few if any prizes, honour in victory perhaps, the challenge mainly from the elements and the difficulties of path and field. Nevertheless competition can be exciting and worthwhile if expressed in a sporting manner. Winning and losing are both of value. To win always would be boring, but equally so always to lose. The challenge is everything.

THE MAN WHO IS ALWAYS SECOND

I was indeed very conscious of the second experience when I became a regular membver of Maryhill Harriers in 2 Mile teamraces. Clubs put forward four members but only the first three were team counters. In addition to team prizes there was always a special prize for the individual winner. We won many team honours against such prominent clubs as Shettleston, Bellahouston, Victoria Park, Plebeian, Springburn, Edinburgh clubs and others, but I was denied individual honours by different brilliant individuals, running well but relegated inevitably to the runners-up position. Perhaps I would finish second to Bellahouston’s Jack Gifford. Next time I might beat Jack, but another Jack, Jack Laidlaw of Edinburgh would storm past me. If I beat Jack next time it would be Jim Flockhart, Jim Ross or Willie Sutherland in monotonous succession.

In fact, the press noticing my constant failure put up the headline, “Farrell, the man who is always second.” Naturally I felt somewhat irritated by this emphasis of my constant failure. So I had to go back to the drawing board. I then realised that most of the lads who beat me were faster over a shorter distance. Some were excellent half-milers and milers and it was customary in these races for a leading group to keep together till perhaps half a lap to go then it was a case of devil take the hindmost. So I tried a new tactic. Instead of waiting till the last lap I put on pressure two laps to go, a risky thing but the only thing if strength and stamina were one’s chief qualities. When I managed to win my first race at Dalmuir in a small meet I was so pleased that when I broke the tape I held on to it and did not discard it for some time. In subsequent races at this distance my rivals invariably scanned the programme to see if I were entered. If so they knew they were in for a hard day’s night because of my tactics.

SIMILAR TACTICS WON THE ROME OLYMPIC 5,000 METRES.

In 1960 at the much higher level of the Olympics, New Zealander Murray Halberg used similar tactics in winning the Olympic 5,000 metres. Bursting into the lead three laps to go he sustained it to the finish holding on to win despite the onslaught of fatigue. Halberg, quite frail with a short arm, the legacy of polio, was a runner of great talent and tremendous determination and character.

(I think the chap in the dressinmg gown beside Johnny Weismuller is George Hackenschmidt: BMcA)

1936, THE BERLIN OLYMPICS

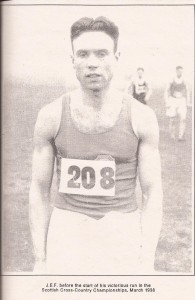

1936 was again an Olympic year and of great interest to the general poublic as well as us runners. Nevertheless the harrier movement enjoyed its own programme of running and the National cross-country championship at Lanark was the big event of the winter season, especially for those aiming to stake a place in Scotland’s team in the international at Blackpool. Nine runners were selected and finishing ninth I looked a certainty for my first Scottish vest, more so as Angus McPherson of Airdrie who finished fifth was a reinstated professional and therefor ineligible. This put me now in eighth position but as two splendid runners, Suttie Smith and WC Wylie, dropped out they were selected on previous form. Thus I was first resrve but did not travel. It is fair to say that Smith and Wylie justified their selection.

THE LOVELOCK-WOODERSON CONTROVERSY

In the 1500 metres at the Berlin Olympics of 1936 Jack Lovelock wearing the black vest of New Zealand ran his greatest ever race to win in the then World Record. Sydney Wooderson the great little Blackheath Harrier who had beaten him twice in England with his dynamic finish before the Olympics had not recovered from injury and was eliminated in the heats. There has been much speculation as to what might have happened had Wooderson been fit and run in the final. In England he seemed to have the Indian sign on Lovelock but it is fair to say that the latter had specially trained for the Olympic event and was a master at peaking at the right time. He trained for both speed and stamina and in breaking the world record he took the lead three hundred yards to go, almost unheard of in those days and none of that world class field could live with him. It was a shame that Wooderson was injured at such an important juncture. What might otherwise have happened we will never know. But argument and speculation will always remain.

THE EBON ANTELOPE

One cannot leave the Games of 1936 without mentioning Jesse Owens who prior to the magnificent modern Carl Lewis was generally considered the greatest sprinter of all time. Certainly he was the sweetest mover as his nickname, the Ebon Antelope, suggests. Four golds fell to this incredible athlete. One hundred metres, two hundred metres, long jump and anchor man in the sprint relay. World class sprinters including our own Allan Wells have been legion since the time of Harold Abrahams each in their own way worthy of mention but I would like to mention just two for different reasons. One was the American sprinter Hayes, who held the world record for one hundred metres but was later to run more sensational times in private. Built like a heavyweight boxer, he ran like a tornado on pure strength and later turned to American football.

WILLIE McFARLANE – DOUBLE POWDERHALL WINNER

What a shame we couldn’t have the great amateur and professional sprinters in competition. Willie McFarlane our own Scottish sprinter won the Powderhall Professional Sprint twice, once off a short handicap and once off scratch. To win twice and especially off scratch represents sensational running. Strong and well-built his times were outstanding especially as they were achieved in the wintry blasts of January. Not the best conditions for sprinters who normally revel in warm sunshine.

CROSS-COUNTRY TAKES OVER

After the excitement of the Berlin Olympics with its thrilling and colourful competition and its political overtones there was naturally something of an anti-climax in athletic interest. However athletes in general soon got down to the old routine enjoying their running and the available competition. Soon the summer was over and the cross-country season beckoned. The season of “mists and mellow fruitfulness” provided a colourful background of red and gold. To run over path and field and woodland was a joy in itself. A feeling that one was oneself part of nature, part of the universe.

The competitive urge was just the icing on the cake. Later as the icy hand of winter arrived there was compensation in the challenge and even then nature tended to present a savage beauty. At the turn of the year, thoughts naturally turned to the big event of the cross-country season and it was specially important to me having narrowly failed to earn selection in the Scottish International team I was determined to make the first six to guarantee my place this time. I had also another point to prove. Away back in 1934 when I was starting my running career a critic wrote of me that I was, and I quote, “an athlete of some versatility but not likely to make headway in cross-country running.” In the light of my subsequent experience I suggest that one should not take critics too seriously but hitch your wagon to a star and keep on trying, keep on practising.

FIERY BAPTISM AT REDFORD BARRACKS.

My preparation was going well. No injuries or winter ills and most of all I was enjoying my running which is always a good sign. In February 1937 I retained my Maryhill club championship by beating Willie Nelson, a previous holder and a very competent and competitive runner. At Redford Barracks, Edinburgh, a most unusual venue for the National, the weather was deplorable with rain, hail and snowstorms. Jim Flockhart was in command and retained the individual title but there was a titanic battle for the other places. Despite lack of experience, I ran a well-judged race. Nine miles in such adverse condition required that. Seventh first time round, fourth in the next lap, I passed Jim Petrie of Dundee and in the closing stages veteran star and Army runner Sergeant RR Sutherland of Birchfield and Garscube Harriers who sportingly shouted “on you go son.” Later I had a quiet chuckle at RR’s expression as I was nearly 28 years of age – but then I always was a late developer.

JIM FLOCKHART MAKES HISTORY

At Brussels, Jim Flockhart ran with exhilarating abandon to win the individual International title from Sicard of France. Before the race in pen pictures of the leading contenders, Flockhart was described as “pauvre petit Flockhart” (poor little Flockhart) a reference to his slim, rather frail appearance compared with others. But after his victory they made amends with the exception “le magnifique petit Flockhart”. My own performance, 23rd and 4th for Scotland behind the experienced Dow and Sutherland, 17th and 20th respectively, was a solid one for my first Scotttish appearance. I was reasonably satisfied but not thrilled. Nevertheless success at any level promotes confidence and increases ambition and though cross-country was my real athletic love I looked forward to a summer season of track and road as a means of keeping in shape and helping speed work.