Alex Dow should be better known than he is. He ran for Kirkcaldy YMCA in the 1930’s, won the SAAA 10 miles track race, ran for Scotland in five international championships and was always in the first three counters at a time when the Scottish team won more medals than in any other decade. The fact that his club was never ever right up there in the rankings or championships of course might have contributed to the ignorance of his career – nowadays he might well be recruited one way or another to a more fashionable club, but in his day good runners ran for their own clubs and were happy to do so. A native of Collessie, he lived in Dysart and died comparatively recently – in 1999 at the age of 92.

A local paper remarks on his start in the sport: “He had rather an amusing baptism in the sport. While with the Black Watch at Perth, he was sent out with a squad to the North Inch and told to run a mile. He won. After that, Dow won several races in the Army. After his discharge from the Army, Dow joined Kirkcaldy YMCA and speedily made his mark.”

He ran cross-country running in the winter of 1933/34 where he did well enough to win the Eastern District title and also took the Scottish Junior title. Colin Shields in “Whatever the Weather” comments that “Alex Dow (Kirkcaldy YMCA) ran away from his rivals to win the Eastern District title by almost a minute at Musselburgh racecourse, the first of many successes that included an ICCU international bronze medal just two years later.” Of the National he commented that he ran well to finish fifth and win the National Junior title. The international that year was held on home soil – at Ayr – and there were hopes for a Scots victory but according to Shields, they were simply ‘run off their feet ‘ after a fast start. Dow in 12th place was the third Scot to finish behind Flockhart (6th) and Sutherland (11th) to gain a bronze team medal.

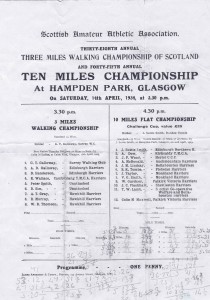

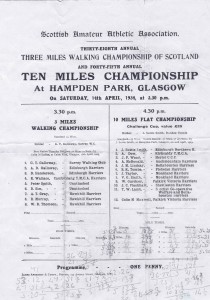

He really sprung into prominence, however, on 14th April 1934 when he won the SAAA 10 Miles Track title. The “Glasgow Herald” reported on the race as follows: “J Suttie Smith, the champion was indisposed and did not defend his honour. A Dow, Kirkcaldy YMCA Harriers, the Scottish Junior and Eastern District Cross Country Champion, gave further evidence of his capabilities by winning rather easily. The champion was the only absentee of the 12 entrants for the 10 Mile Race. Once the runners settled down, it was seen that JC Flockhart, the Scottish Cross-Country Champion, A Dow, SK Tombe and JF Wood had the title in their keeping. They ran in the above order for seven and a half miles, at which point Dow went to the front for the first time. Flockhart and Tombe were close up at this stage but Wood had dropped back and seemed out of the running. Once in the lead Dow drew steadily away. Running strongly and in effortless style, the Kirkcaldy man went on to win his first SAAA title by some 200 metres. Tombe also finished strongly to beat Flockhart by 50 yards. The intermediate times were:-

One Mile 5 min 11 2-5th sec; Two Miles 10 27 3-5th; Three Miles 15 min 46 2-5th sec; Four Miles 21 min 07 sec; Five Miles 26 min 27 1-5th sec; Six Miles 31 min 32 2-5th sec; Seven Miles 37 min 13 1-5th sec; Eight Miles 42 min 36 sec; Nine Miles 47 min 51 4-5th sec.

1. A Dow 53:12; 2. SK Tombe 53 min 40 2-5th sec; 3. JC Flockhart 53:49.

Alex Wilson, who gave me a lot of the information for the profile (and who in turn owes a debt of gratitude to Don Macgregor, who is not only a great runner but an athletics historian), has been good enough to send me a copy of Dow’s own extract from the race programme with splits taken on the day by one of his entourage.

As Alex says, with splits of 26:27 and 26:54 he wasn’t a bad judge of pace. When it is borne in mind that his club did not have access to proper track for training, it is remarkable that the pace should be so even – the YMCA trained in the Beveridge Park, on grass, meetings were evidently held in Stark’s Park too in those days, but the harriers obviously didn’t have access to a cinder track.

In the following cross-country season, 1934-35, he won the Scottish YMCA championship, and then Dow was seventh in the National behind Wylie (Darlington), Flockhart, Suttie Smith, Freeland, C Smith and William Sutherland. Excellent company to be in. In the International on 23rd March in Paris, he was second Scot to finish when he crossed the finishing line in tenth place with only Wylie (second overall) ahead of him. Flockhart, Suttie Smith and the rest were behind him: the “Glasgow Herald” simply said “Alex Dow (Kirkcaldy YMCA and 10-mile champion) again rose to the occasion, gaining ground steadily to finish tenth.” The local paper described it as a “Splendid, judicious race.”

Into summer 1935 and Alex was again competing in the SAAA 10 Miles track championship: this time he finished third behind Willie Sutherland and Jimmy Flockhart. He gained another medal in the National Championship at the end of the cross-country season when, according to Shields, he was as far back as thirteenth at one point but came through to be third at the finish. About the International in Blackpool, we read , “Alex Dow in all his five Scottish international appearances in the 1930’s, was never outside the first three scorers for the Scottish team, displaying a natural ability that gained him many victories without any great training schedule or hard work behind him. In the 1936 international Dow was at his best over flat fast course with scattered artificial obstacles. He was part of a team that included three men – J Suttie Smith, RR Sutherland and WC Wylie – who had all finished runner-up in recent years, but the main Scottish hope lay with James C Flockhart who was undefeated all season. The race was run in blazing hot sunshine and Dow, accustomed toi the torrid heat from his Army service in the Far East, was more at home with the weather than his colleagues. Starting in tenth position after the opening rush, he was eighth at half distance, sixth at 6 miles, and a relentless surging finish brought him home third, just six seconds behind Jack Holden, a three times winner, with British 6 and 10 miles record holder William Eaton finishing a clear winner by a 150 yard margin.”

1936 International Cross-Country Championship: Dow is Number 55

A local paper at this time described his training: “Dow trains on Tuesdays and Thursdays over the road varying his distances from three to five miles, and covers seven miles over the country on a Saturday. Dow does not bother himself unduly about diet, and ha so far failed to set for himself any special course of training for big events – more proof of his natural ability. No present day runner covers the ground with less effort. If one carefully watches his striding methods, it will be observed that his leg lift is of the minimum height, reminiscent of the style of the great Arthur Newton of South Africa who holds many long distance road records.”

If his selection for international duty so far had been eminently clear cut, this was not the case for 1937. He finished 102nd in the National at Redford Barracks in Edinburgh and was selected to run for Scotland. It had been the case that the first six were automatically selected and I don’t know of any runner finishing outside the first 100 to be picked for the International. Alex Wilson has looked into this carefully and has this to say: I have found some interesting stuff on Alex Dow’s selection for the 1937 ICCU Championship. It seems that it was the subject of heated debate. Many felt that the running order in the national championships should be the sole criterion for selection rather than the, in part, discretionary selection method favoured by the SCCU. According to Athlon (an athletics journalist) ‘This year the Scottish officials accepted the first three men – Flockhart, Farrell and Sutherland – without discussion, but all the others were put to the vote.’

One item (source unknown) re the Scottish Cross-Country Championships states: ‘The most remarkable failure was that of Alex Dow of Kirkcaldy YMCA. During the season Dow has hardly shown the form expected of him, but few looked to see him fail to finish inside the first 100. The Union, by including him in the team for Brussels, have shown they keep their confidence in him, and certainly his distinguished service in the past gives a guarantee that his form on Saturday was a temporary lapse. Dow may make a good recovery at Brussels.’

Another item states: ‘One of the most distracting features of the Redford race was the running of Alex Dow, Kirkcaldy, who finished only 102nd. His loss of form seems inexplicable, but bearing in mind his brilliant running for Scotland in previous races, the selection committee has given him a place in the team again.’

Athlon wrote re the ICCU selections: ‘I do not think the team is open to much criticism. the selectors have evidently chosen A Dow on the strength of his last season’s running, when he finished third in both Scottish and International championships. I believe the Dysart man has been troubled by a leg injury, obviously he was not fit on Saturday, for more than a hundred competitors beat him. I am not finding fault with the Union selectors in finding a place for Dow, but I think they are being rather inconsistent. Only a couple of years ago they left out RR Sutherland because he only finished 26th in the national event. Last year however, they chose WC Wylie after he had run 44th in Lanark, and he did not let them down in Blackpool’.

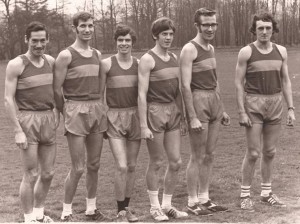

The 1937 International team – Dow on the extreme left

The 1937 International team – Dow on the extreme left

So how did he do in the international after so much ink had been spilt over his selection? Second Scot across the line, in 17th position, beating RR Sutherland by three places! The story of the day however was not his return to top form but rather team mate Jim Flockhart’s victory. Read about it here. The “Glasgow Herald” after devoting almost all of the report to Jim Flockhart had a paragraph that said: “Alex Dow fully justified the confidence of the Scottish selection committee. In finishing 17th he was second counting man for his country, beating RR Sutherland by three places. JE Farrell “stitched” badly at one point of the race but hung on grimly and eventually finished 23rd and fourth for Scotland.”

Alex Wilson’s comment is that “in the 1930’s at least the Scottish selectors had an uncannily good hand. These were clearly people with their ears close to the ground.” My own perspective is that at present selectors find many ways to avoid actually having to select a team – automatic qualifications, rigid trials, etc – and the thought of picking a runner who had been out of the first 100 in the national would be a boldness too far!

1937/38 was Dow’s last year and the 1938 international was his last. The national was to be held at Ayr in 1938 and 30 prominent runners were invited by Captain WH Dunlop to go for a training run over the course to familiarise themselves with it before the actual race. The race was on the same day as the English national so RR Sutherland missed it as did WC Wylie. John Emmet Farrell won the title by 150 yards from ‘a fresh looking Alex Dow‘ and PJ Allwell (Ardeer). The international was held at the Balmoral Showgrounds in Belfast where the Scots all ran poorly. Dow was 27th and third Scot. Some Press reports said that he had been second in the national despite not having trained hard and the Glasgow Herald report on the international, after lamenting the poor form of the Scots generally and the disappointing team performance had this to say of Dow: “A Dow found conditions against him and, in extenuation of his failure, it is remembered that he rarely does well except in fine weather and on firm ground. The race at Belfast was run in driving rain.” That is consistent with the reports of his run in 1936 where it was reported that the hot weather and blazing sunshine had suited him after his Army service in the Far East. He was however third Scot to finish.

He ran in other races – eg two weeks before the international he ran a fast time for his club in the Perth to Kirkcaldy Road Relay – but his international career was finished. If you look at any of the team photographs you will see that, along with RR Sutherland, he was the tallest in the team – probably over six feet – and it is no surprise to find out that he was a policeman. He took up a post in Palestine in 1939 his running career, as far as we know it, was at an end.

Like many of his generation, Dow was a very talented athlete who had a short career – the length of which was dictated by his occupation, it was terminated by his occupation too. If we look back at his ten miles triumph in 1934, the pace judgment was immaculate and in most of his races he tended to run steadily throughout and come through dramatically when others were tiring. This was done without the assistance of pace training on a track although it is possible that his road runs were what we would today call ‘tempo runs’! The country was blessed with many fine athletes in the 1930’s – possibly a golden generation?