The beginnings of harrier running in relation to Scotland are difficult to pin down. Much of the research and history seems to start rather abruptly at 1885 on the formation of Clydesdale Harriers. Apart from fleeting references to a Towerhill AC in the north side of Glasgow prior to that and other references to hares and hounds activities of the universities (specifically in England), there is virtually nothing to guide us as to how the first clubs came to be formed in 1885. Runners simply could not have emerged spontaneously from the ether! What emerges is a complex of influences and traditions that at times stand alone, sometimes change and alter as a consequence of changes in civil society, and of course merge and diffuse. Quite probably (although by no means certain) they arise from the following areas or sources of activities.

In the first instance, the societal groupings of the clan system and their running footmen and races between these footmen, plus the emergence later of Games and traditions associated with Fairs, contributed in the nineteenth century to a sense of ‘National Games’. Highland regiments also played a key role in re-defining Scottish sporting traditions as a major part of the Scottish contribution abroad to the emerging Empire.

Secondly, the new sports clubs were, in part, a consequence of rapid urbanisation and influenced by the new Public Schools and their subsequent development and invention of new ‘sporting forms and traditions’. In amongst this, the nineteenth century witnessed political and social shifts that came to be reflected in the various sporting forms. From ideologies such as ‘athleticism’ and the ‘muscular Christian‘, to shifting values around ‘respectability’ such as drink and temperance, pleasure grounds and ‘acceptable’ sporting engagement. Clubs of all sorts (and belonging to them) became a hallmark of the Victorian young male.

Scottish running traditions are assumed to have their roots partly in the traditions of clan systems and running footmen. There is the reasonably well-known historical tradition of running footmen kept as retainers as message carriers with references as far back as Malcolm Ceann-Mor in the eleventh century and the hill race up Creag Choinneach race. Changes in local traditions and the nature of local Games also changed with variations to events and structure reflecting local and eventually area variations. In this regard races on foot, although usually to a local well-known vantage point and back, also changed. Societal changes, especially in the eighteenth century also meant changes in leisure time pursuits. Games of villages and the Games associated with Market and Fairs Days took on greater significance with races over ‘rough terrain’ for prizes of goods such as tea and cloth as well as (in some cases) money. Highland Regiments (deployed mainly abroad) also played a significant role in maintaining the notion of a Scottish ‘tradition’ through regimental Games, and competition was encouraged between regiments with running races over different distances a feature of inter-regimental competition.

(One fascinating piece of related history, although it is not connected to any particular Harriers Club, is the ‘Red Hose’ Cross-Country race, which claims to date from 1508! This takes place annually in Carnwath, Lanarkshire. The Guinness Book of Records recognised the event in 2006 as ‘The oldest road race in the world’. Well, it was certainly cross-country back in the 16th Century – and recent photos (do check for more details online) show runners starting on grass. This traditional 3 Miles race has a pair of long red socks (or hose) as the prize. It was originally held around the Feast of St John the Baptist in June, but has now been absorbed into the Carnwath Agricultural Show in July. This is a well-loved local event and organisers are keen to keep the tradition alive.

James IV, King of Scots, in 1508 gave a Charter of the Lands of Carnwath to John, third Lord Somerville, in the following terms: “Paying thence yearly….one pair of hose containing half an all of English cloth at the feast of St John the Baptist, called Midsummer, upon the ground of the said barony, to the man running most quickly from the east end of the town of Carnwath to the Cross called Cawlo Cross…” There was probably a military reason for imposing this duty on the owners of Carnwath. A fast runner could bring news of any approaching invasion from the South to Edinburgh, and the Red Hose would be the insignia by which he would be recognized. In olden days the event was so prestigious that the name of the winner was cried from the Mercat Cross in Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland. Although the lands of Carnwath have been sold down the years, the local Laird Angus Lockhart of the Lee must still provide a pair of red stockings as the prize.)

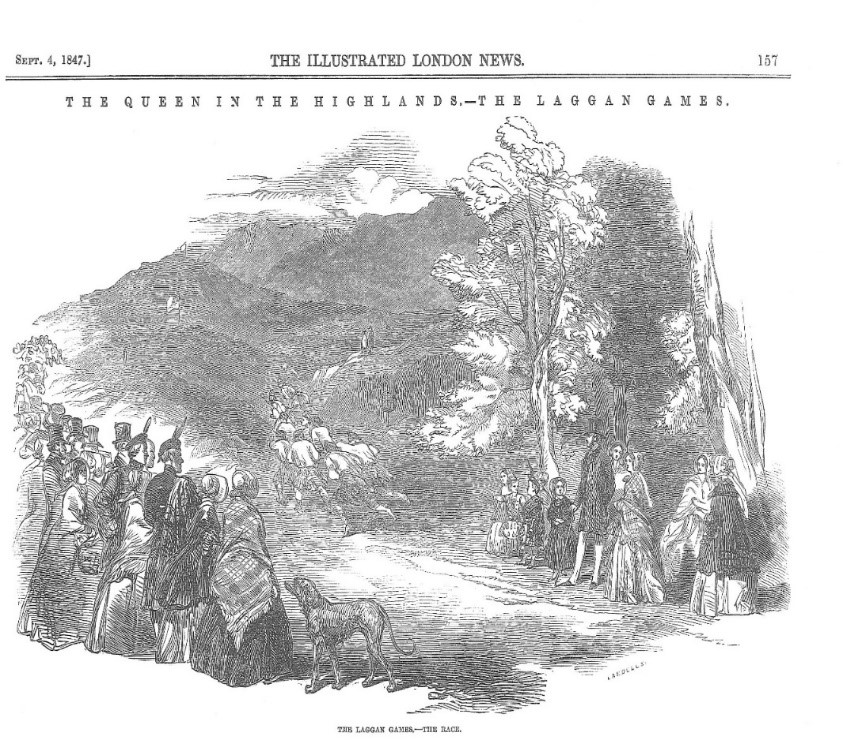

From the early to mid-nineteenth century, ‘Balmorality’, Highland Games and Highland regiments, alongside new urban forces, created greater leisure time and modified activities better suited to the new urban classes. The impact of Victoria and her fascination and regard for everything Highland was to encourage the continuation of old ‘traditions’ as well as the invention of new ones. Her visits to Scotland and the acquisition of the Balmoral Estate in 1842 marked a turning point in the visibility of Highland Games. Victoria and Albert attended the Braemar Gathering in 1843 and her subsequent visits gave an impetus for the invention of the ‘romantic’ landscape of Scotland as a place and site of physical endeavour in accord with the rugged landscape. The illustration below (of ‘The Laggan Games’), one of the earliest of its kind, is a good example of this new and often exaggerated activity.

(Illustration supplied by Hamish M Thomson)

- In 1847 Victoria and Albert stayed at Ardverickie House (the setting for the TV programme ‘Monarch of the Glen’) on the shore of Loch Laggan for 3 weeks as a guest of the Marquess of Abercorn who had leased the property. Abercorn was ‘Groom of the Stool’ to Prince Albert. There is no record of there ever being a ‘Laggan Games’ but it would have been reasonable to assume that the host would have put on some form of ‘traditional’ activities during their stay, of which ‘The Race’ would have been one. Victoria and Albert are depicted on the right of the picture.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, there was a growing leisure ‘industry’ based on the new work/leisure balance. Betting and wagering in sporting activities had become well established by the eighteenth century. Walking and running races (Pedestrianism) became popularised as part of this as sites of not only physical endeavour, but also speculation. The Games of Scotland attracted large crowds to local Games to see ‘names’ with the attendant ‘evils’ of betting and wagering (also by the competitors themselves).

At the same time, emerging from the ‘Enlightenment’, gentlemen’s clubs and other homosocial groups also contributed to a sense of sporting traditions. It is here that we start to get distinctions in the forms that races took. Steeplechases were popular and took the form of short (sometimes very short) races from one point to another by any route (and also by return). It is suggested that a distant local church steeple lent its name to the form. Hares and Hounds also started to become popular sometimes called Paper-Chasing or Paper Hunt.

A few examples of these clubs are The St. Ronans Border Games at Innerleithen whose third meeting in 1829 featured a ‘Steeplechase ….. a race up The Curly and back’. The Ettrick Border Games also featured at this time in what appears to be a relatively rich cross border development and according to one source, ‘although cotters and the rustic population engaged in them, the large majority of competitors belonged to the upper classes, and the lairds were oftener prize takers than their tenants.’ Associated with the Ettrick Games is James Hogg (The Ettrick Shepherd) and both Christopher North (aka John Wilson – Professor of Moral Philosophy at Edinburgh University).

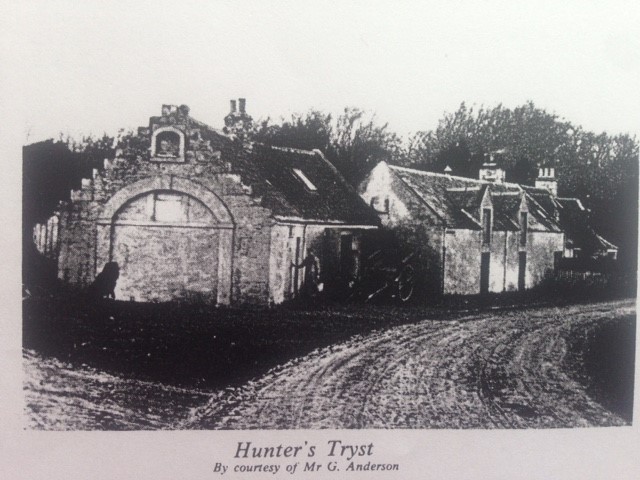

A further final example of these emerging clubs and their interest in ‘Scottish Sporting Traditions’ and runs over open country, is that of the Edinburgh Six Foot Club. Founded in 1826, the club included many of the literary figures of the day (despite not being six foot tall). Members included Sir Walter Scott, Christopher North (again), James Hogg, Adam Wilson, Henry Glassford Bell and Lockhart (Scott’s biographer). Its object was to ‘practice the national games of Scotland and gymnastics’. In addition to their town gymnasium first in East Thistle Street and then later at Malta Terrace, it also met at an Inn at Hunter’s Tryst some five miles outside of Edinburgh on the Oxgangs road to take part in field and outdoor events.

In 1828 there was a Steeplechase of one mile for a silver watch. Eight competitors took part and M. Wilkie won in a time of ‘three minutes and a half’ (sic). Apparently, there were many ladies present.

Some of the associated practices around the Six-Foot Club Club resonated later in the formation of the Harrier clubs. Firstly, there was a distinct class base which is unsurprising given the time constraints of ordinary working men of this period. Secondly, there is the fondness for trappings and trimmings of nineteenth century clubbable men. Medals and cups, membership levels of ordinary members and honorary members with meetings in club rooms and at the gymnasium. Also, there was the uniform of the club of ‘the finest dark green cloth coat, double breasted with special buttons and a velvet collar. The vest was of white Kerseymere. Trousers were black. On special occasions a tile hat was worn.’ The Six-Foot Club clearly had influence as they were appointed ‘Guard of Honour to the Hereditary Lord High Constable of Scotland’ in 1828. The Harriers clubs were to adopt Patrons with the same enthusiasm, vying to attract the great and the good in positioning their club within sport and civil society. The Six-Foot Club has been described as the ‘thinking man’s fitness club’!

The 19th century therefore began to see developments in sport alongside the growth in industrialisation. Increases in leisure time (for some), new class divisions with the attendant aspirational activities designed to allow ‘getting on in life’ and increasing mobility of population enabled new sporting forms to develop and flourish. Pedestrianism was one such popular form and is well documented and was key activity in bringing feats of running prowess to a wider public through a growing interest in both the national and local press of the day. Betting and gambling based on many of the emerging sporting forms included feats associated with endurance running and attention soon turned to combatting the ‘evils’ of gambling (associated with the lower classes) while wagering (more acceptable) was associated with the new middle classes. The need to organise and manage these new sporting forms therefore became of critical importance for a variety of reasons and it was in 1850 that a key catalyst emerged in relation to running.

The expansion and formation of many sports and clubs occurred from 1850. Up until then the life of the ordinary person was such that they were unlikely to travel on any regular or semi-regular basis outside of an immediate radius of where they lived and worked. The expansion of the railway system and the eventual half day non work time every week (one hesitates to say half day ‘holiday’), were key drivers in the development of leisure time activities. The 1850s therefore, was probably the moment when the sports and pastimes of the middle and upper classes began to feel the interest of those with new leisure time. The tensions between those sporting forms based on the gentlemanly ethos of manliness, athleticism and the young male as a muscular Christian with service to Queen, country and Empire (ensuing largely from the Public Schools from the 1830s), started to attract the attention of those whose backgrounds were not as privileged. Steeplechasing, paper-chasing and hares and hounds all gathered interest from those new industrial classes. Sporting activities were to become codified and organised on a more formal basis in order to exercise greater control and ‘police’ developments. Sport was to serve a purpose.

The social context for sport in the nineteenth century emerged from a mix of political upheaval and the extension of voting rights and an emerging new class structure. The development of amateurism (mainly an ethos of both the old and new public schools) was seen as masculine, militaristic and patriotic. Sport was a place that defined true heterosexual men; ‘making men’ in effect. The influence of ‘traditional’ sports was declining. By the nineteenth century there was also a new nationalism sweeping across Europe which used athletic activities as a way of inter-twining sport and nationalism. Britain was developing its ‘Games ethos’ while Germany had its Turnverein (Turnen) movement (overtly nationalist) of Guts Muths and Friedrich Ludvig Jahn (‘Turnvater Jahn’). In Sweden, a similar movement to restore Swedish culture and national pride was led by Per Henrik Ling with ‘exhibitions’ known as ‘Lingiads’. The Czech based Sokol movement was also part of the nationalist sporting movements of Europe. With new social conditions emerging from industrialisation and urbanisation, a new focus to produce men (not women) of the right calibre to serve the Empire refocused sports; leaving some behind, while other forms developed. George Roland’s fencing and gymnasium rooms in Edinburgh was one such example of absorbing different sporting forms.

Harrier activity as one of those sporting forms was, by the 1830s, embedded in most English Public Schools with versions of running races, variously Steeplechases or forms of Hares and Hounds. Shrewsbury by 1819 had a Hares and Hounds run known as The Hunt, Rugby had its Crick run by 1837 (hares and hounds) and Eton had a Steeplechase by 1847. At Wellington it was Charles Kingsley himself who instituted the run and the course. Other schools such as Winchester and Harrow also developed runs. The evidence (so far) of Scottish Public School equivalent school runs at this time, is negligible. The Scottish system differed, but there were schools of long standing such as the High School of Glasgow (pre 1124), the Royal High School Edinburgh (1128), Hutchesons Grammar School (1641) and both Edinburgh Academy (1824) and Glasgow Academy (1845). It may well be that further work is needed to establish whether these schools had their equivalent run.

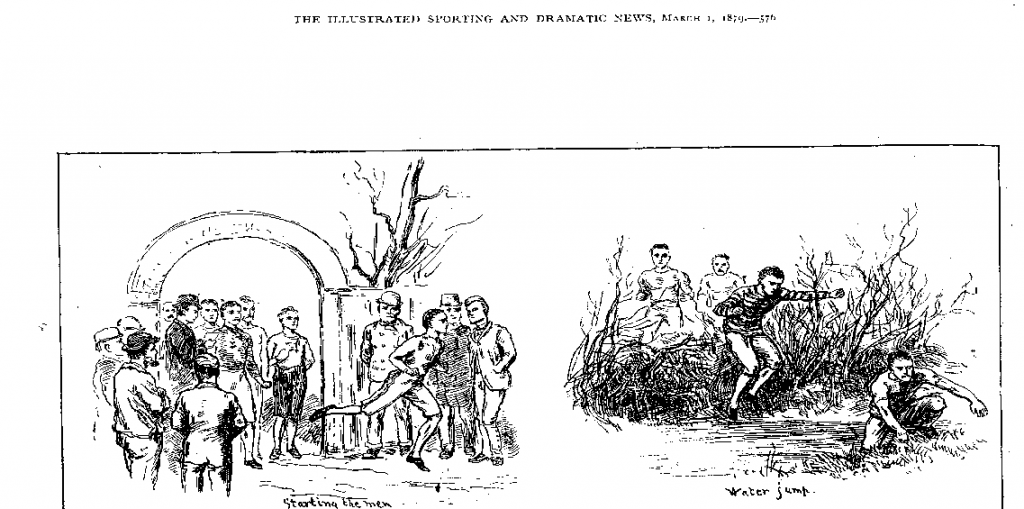

Source: The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News. March 1st, 1879 p57

Many of these young men took those traditions into the Colleges of the universities they attended and while the Crick run of Rugby School is associated with the earliest form of cross-country running, it is the students of Exeter College, Oxford who arguably get the credit for the modern version of Cross-country with a College ‘Chase in 1850. While much of the foregoing is Anglo-centric, it allows for a certain understanding of the diffusion of the sport and given the relationships that existed in the structure and governance of the two countries at the time, there is substantial evidence to suggest that some diffusion occurred through university educated men teaching in schools in Scotland and contributing to the culture of the school by encouraging running.

More frequent reporting in the press and an increasingly literate 18-35 age group, meant that young men were able to engage with the new forms of ‘acceptable’ activities. There are examples emerging by the 1860s of sports days held by former pupils of Edinburgh schools. Edinburgh Academy then Merchiston Castle, followed in 1864 by the Royal High School all held Sports Days and some included ‘strangers’ races’. The schools themselves soon followed suit and by 1866 the first Edinburgh Inter-Scholastic Games were held, witnessed by ‘thousands of spectators’. Glasgow Academy soon followed and the Glasgow Academicals Club were formed in 1866. This was what would be termed today a multi-sport club which practised runs over the country and they held at least two ‘Paper Hunts’ early in 1870. Athletic events were held each spring by other schools and clubs on the banks of the Clyde.

St Andrews University held a paper-chase in 1870. In 1871, some 5 years after forming their University Athletic Club, Edinburgh University held a Spring Steeplechase and by 1872 had formed its own Harriers club. Edinburgh University in particular had a tradition of games going back to the 15th century when Regents used to supervise students playing on the Borough Muir. There is also an account of RL Stevenson commenting on medical students running up Arthur’s Seat.

One detailed example of the influence of the Edinburgh schools in encouraging running activities comes from an account from George Watson’s College. The school itself did little to formally encourage such activities, most of the activities being pupil led. WL Carrie, a Master at the school (Head of English) seems to have been a particularly powerful influence at in the early 1870s. During the period of the 1870s to 1880s, the boys played games on the Meadows of Edinburgh where the recollection of John Patterson (winner of three successive cross-country titles from 1898 to 1900) is that of ‘sixty-a-side soccer with a threepenny rubber ball ….. and Hares and Hounds through the Grassmarket.’ Attire was eclectic; ‘Long stockings with tight garters above the knee, and our short breeks were puckered with another elastic round the knee’. There were at least eight public schools in Edinburgh at this time who may have adopted and practiced a form of hares and hounds from time to time. The influence of Tom Brown’s Schooldays and the proselytising Head Teachers such as HH Almond of Loretto near Edinburgh, made the case for the importance of certain sports in order to produce ‘a race of robust men, with active habits, brisk circulations, manly sympathies and exuberant spirits’ for purposes of Empire. To be part of these new, respectable sporting forms was aspirational for many young men.

Into this however, fed the Victorian obsession with vice. This was partly in response to what was seen as a need to control and civilise the new urban masses as much as it was about defining ‘respectable’ behaviour and activities. There was of course much debate about what constituted ‘respectable’ behaviour but the strong anti-vice campaigners of the day, mainly the new middle classes, were skilled in using movements such as the Nonconformist ‘conscience’, the Quaker movement (anti-gambling) and the temperance reformers. Sporting activity came under scrutiny and so gymnastics, games, rowing, swimming and eventually cycling all came under the gaze of respectability. Harrier activity, arising from the runs at public schools and subsequently universities, then became one of a number of ‘acceptable’ sports often attached to ‘Athletic’ Clubs (multi-sport clubs of today) or gymnastic, football, rowing, swimming, cricket and cycling clubs before taking off in their own right by the mid-1880s. A number of harriers by the 1880s came from gymnastic clubs who had harrier sections as well as from harriers sections of other sports such as football, rowing, cycling and cricket (the West of Scotland Cricket Club was a particular adherent of ‘athletic meetings’). The scene was set for the aspirant male of the late nineteenth century to see sport as one of the more respectable and acceptable ways of making one’s way in life. Attachment to a sports club brought a cachet (if one could join) and meant connections to ‘get on’ in life which chimed with the ‘Self-help’ ethos of the time.

Harrier activity (or paper-chases, Hares and Hounds or Steeple-chasing) in Scotland was occasionally used as an alternative to a game in adverse weather or as an adjunct to expand the ‘portfolio’ of a club’s activities, it is clear from the reporting in local newspapers in Scotland that although certainly known, it was considered a peripheral activity. Reporting in the press to satisfy public interest was intermittent and haphazard until the 1860s. Newspapers largely relied on this kind of information being fed to them by an interested party and even then, usually attached to an identifiable organisation such as a school, university or club. The main sports encouraged were cricket, football (both codes) and Sports Meetings or ‘Athletic’ Meetings which were usually grand occasions, with large crowds and held under the patronage of some civic notable.

One of the earliest references is that of the Maryhill Grand National Games in 1866. In the same year the Glasgow Academical Club was formed at a meeting in May. In 1867 there were ‘Athletic Games’ under the auspices of the Glasgow Athletic Club at the Stonefield Recreation Ground, south Wellington Street, Glasgow to which 800-900 attended. In 1866 there were references to the annual ‘athletic sports on the banks of the Clyde’ such as those at Abingdon House the home of Sir Thomas Edward Colebrooke MP. Athletes included ‘professionals’ as well as ‘amateurs from the surrounding parishes’ and ‘trained athletes’. The afternoon was rounded off with a 6 mile race.

In 1870 Queens Park FC had a harrier run between members in October of that year, while in the same year the Glasgow Academical Club held a paper-chase from Bishopbriggs and back to their Club HQ. The first overt mention of a ‘Hares and Hounds Club’ comes in 1872 with the Glasgow Hares and Hounds Club who held a run over 7 miles from Regents Park on the Dumbarton road and finishing the day with a tea courtesy of a Mr Matthew Wilkes.

Harrier running (or paper-chasing) was also popular with football clubs who were also ‘Athletic Clubs’ in name (to be an Athletic Club perhaps made more of a statement than a Football Club). Alexandra AC was set up to ‘practice athletic and field sports’ but was principally a football club. This was no bunch of lads coming for a kick around. They had enough behind them to be able to lease land adjacent to Alexandra Park in Dennistoun (then a leafy suburb of Glasgow), and also erect a ‘house’ for members for inclement weather. It had the patronage of the Earl of Glasgow. By 1877 they were engaged in Hares and Hounds with a 5 mile run on July 9th. Queens Park Football Club were still sufficiently involved in Harrier activity to earn the nomenclature of ‘Hampden Harriers’ in 1880. By 1879 Edinburgh University were inviting footballers to run with them (27th December, 1879).

Interest in Harrier running/Hares and Hounds was clearly filtering through the school systems in Scotland at this time too. In an address to the Stewartonians at their 10th annual reunion in the Albert Hall in Bath Street, Glasgow in 1875, Thomas Young (chair), a merchant in Stewarton, reminisced about his boyhood days and how he ‘played at ‘Hares and Hounds’ o’er Corsehill Braes, the Thornefa, the Merry Greens and Bessie’s Braes’. Herbertshire Castle School at Dunipace held ‘Sawdust Chases’ for a number of years after opening in 1877. JW Reid teacher of classics, chemistry and mathematics at the school was also a ‘gymnastics gold medalist’ so may have been a key facilitator in ‘Sawdust-chases’. He was a vice-president of the Dunipace Temperance Association with another master of the school a trustee (Thomas R Wilson). Paper-chasing was one of the ‘traditional’ activities by now of a public school and was part of the active ideology of the day and therefore fitted the temperance principles. The fondness (or otherwise) for the activity was often caught in the form of poems by the boys. In one poem published in 1880 titled Adieu to School, the pupil is keen to appear wistful and in stanza three he says

Farewell my tops and peeries too

Whose whirring hum my fancy drew!

Adieu the nimble steps and bounds

That served me well at ‘hares and hounds’!

Near the end in stanza 7 there is the hope that

… On other ‘grounds’ perhaps we’ll meet

In life’s untrodden field.

(A.M. in North British Advertiser and reprinted in The Fife Free Press, Saturday 31st July, 1880, p6)

Herbertshire Castle School

Of further interest are the various forms of hares and hounds that were part and parcel of other clubs such as the Ardgowan and Inverkip Hares and Hounds Hunt. In a series of detailed accounts from 1876 until at least 1883, there were a series of runs at Inverkip on the Clyde. The first race in 1876 was over 6 miles for a silver cup and was part of the New Year’s Day celebrations. Some two hundred people turned out to watch the race depart from the Old Kirk, the starter and judge being the owner of the Inverkip Hotel, Mr James French. There was also intimation of a further run the following week. The Ardgowan and Inverkip Hares and Hounds met the following year New Year’s Day and there is a detailed account of the race with attendant explanation as to what a Hares and Hounds race was since ‘this field sport is not indigenous to Scottish soil, being imported from the sister country’. The 1877 race benefitted by the attendance of the local estate owner, Sir Michael Robert Shaw Stewart and his wife Lady Octavia. By 1879 the race was clearly a major event as the prizes had grown from a cup and a handful of prizes to a silver lever watch, 3 monetary prizes, a woollen jacket, leather leggings, silk handkerchief and a silver mounted pocket knife. The recipients ranged from two gardeners, two quarrymen, a gamekeeper, saddler, stableman and a ‘second’ horseman all presumably employed by the Estate.

Such occasions however are seldom without local commentary and misunderstanding. It is recorded that in conversation with a friend on the Inverkip Road and old man was entreating his friend not to go further as ‘the lunatics had broken out of Smithton and were flying across the fields in a cluster … pursued by a man on horseback.’ He could not be persuaded that this was a race. The 1882 account of the race records the fact the many of the gentry and their wives accompanied the race on horseback and there were 19 ‘hounds’ who had been in training for the race. There was clearly a developing awareness in the district of paper-chasing since Aldergrove FC of Port Glasgow held a paper-chase in April, 1880 with the intention of a further race to which other clubs would be welcome.

While at first glance, there may seem a ‘head of steam’ in interest for paper-chasing, which might have resulted in more clubs being formed, paper-chasing was still generally an adjunct activity or at best a section of an Athletics or football club. By 1881, hares and hounds activity as part of the Alexandra FC club had died out. Contemporary commentary recounts that ‘Cross-country has never found favour north of the Tweed. It is essentially an amateur sport, and amateur athletes, until a very recent period, were a small minority of the population.’ It goes on to confirm that it is essentially a winter activity only indulged in to keep in condition as it ‘improves the wind.’ It also talks of ‘wheelmen’ who are precluded from their sport due to the heavy state of the roads who would benefit from the formation of a paper-chasing club. A further report in the press talks of getting up a club for ‘hares and hounds hunts’ which were ‘great fun’ in the public schools and mentions the influence of Tom Brown’s Schooldays. It goes on to make the case for the ‘ease of getting into the countryside around Glasgow’ such that ‘when the ground is too hard for football and the ice too thin for skating … it would amuse both spectators and those taking part.’

It was Towerhill AC however, a football club, that is most commonly mentioned immediately prior to the formation of Clydesdale Harriers in 1885. Towerhill, as has been mentioned in relation to other football clubs, staged hares and hounds runs from time to time from their ground at Hopeton Park, Springburn, Glasgow. Towerhill were one of the west of Scotland’s oldest football clubs and there is mention of them in relation to a match in 1874 having just recently formed as ‘adopting association rules’ and ‘a uniform of blue cowls, two-inch orange and blue ringed jerseys.’ There were other attempts in the 1880s to develop an ‘Athletics club’ for Glasgow with a meeting at the Athlone Hotel, Glasgow on 6TH October, 1882 signed by TG Connell, A McCorkindale and AD McGillivray and a further meeting on 13th October with ‘a membership of 30’ under the presidency of RC McKenzie (Glasgow Acad.). Nothing seems to have transpired from either of these attempts and they may well have been more related to Athletics Meetings than Hares and Hounds. In Edinburgh St George Football Club (Rugby) and the Northern Cycling Club both had runs of a hares and hounds nature in the early 1880s and it was the initiative of the St George club that ultimately led to the formation of Edinburgh Harriers in 1885. Peter Addison of both Edinburgh Harriers and Edinburgh Northern Harriers is known to have been a harrier member of St James FC (Edinburgh) one of a number of ‘football’ clubs practising other sports prior to the formation of the Edinburgh clubs.

In attempting to draw threads together to gain an insight as to the nature of harrier running prior to the formation of our oldest surviving club, Clydesdale Harriers, it has not just been an issue of investigating the clubs themselves, but also delving into the contexts too. There were not only societal influences, but also sporting forms changed to suit the new emerging social and political fabric of the day. Some further thoughts emerge. One of the reasons for a potential lack of development much earlier (along with other sports) could have been the lack of a fixed venue or home for the activity (by definition). Added to this is the large-scale betting industry of the nineteenth century which found pedestrianism attractive (often fixed venue, ability to advertise events and often very large crowds), but hares and hounds less so. Scottish soccer has been described as ‘a big business’ by the 1880s and spending on sport in late Victorian Britain was estimated to be about 3% of gross national product. Harrier running, by its very nature, over large tracts of land and therefore hidden from spectator view was perhaps less appealing and less under this new commercial leisure control compared to the track (athletic) meetings. From its historical roots through to its partial resurgence as one of the ‘Scottish Pastimes’ and into the public school era as a tool for moulding young men in the image of Empire and respectability, running over the countryside evolved by the 1860-70’s as a form of sporting engagement firstly as part of the ‘new’ athletic clubs and as an adjunct to existing sports clubs, to full view as a sporting activity in its own right. By 1885, Harrier running was now part of the sporting cultural capital of aspiring young men.

Sources: The following is a list of some of the sources which were used and can be followed up for more detail.

Brander, M. (1992). The Essential Guide to Highland Games. Edinburgh, Canongate. (for brief history of development of Highland Games)

Collins, T (2013). Sport in Capitalist Society, Routledge, Abingdon p 41 taken from Marshall, F (ed) (1892). Football: The Rugby Union Game. London p55 (for the quote by HH Almond)

Collins, T. (2013). Sport in Capitalist Society. London, Routledge. (for a brief critique of changes to society in nineteenth century Britain and how they affected sport)

Gibson, J. (1903). The Lands and Lairds of Denny and Dunipace (for the illustration of Herbertshire Castle)

Huggins, M. (2004). The Victorians and Sport. London, Hambledon and London. (for attitudes and values associated with sport in nineteenth century Britain and the sports themselves)

Huggins M. (2016). Vice and the Victorians. London, Bloomsbury. (for the relationship between ‘respectability’ and sport)

Jarvie, G. (1991). Highland Games. The Making of the Myth. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press. (for a more critical review of Highland Games)

Radford, P (2015) Six Feet Club, Edinburgh. An extended note (as pdf) in Athlos www.athletics-archive.com

Smith, CJ (1979). Historic South Edinburgh, Vol 2. Edinburgh, Charles Skilton. (for Six Foot Club)

Sports Quarterly Magazine No 15 for sources on Six-Foot Club and Sports Quarterly Magazine No11 for sources on the St Ronans Games and other Border Games. National Archives of Scotland G-D445/4/15

stronansgames/history.org (for information of St Ronans Games and Border Games)

Telfer, H (2006). The Origins, Governance and Social Structure of Club Cross Country Running in Scotland, 1885-1914. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Stirling.

Wilkinson, HF (1875) Modern Athletics 2nd edit. London, Warne. (for early Scottish athletic sports of 1860s and 70s)

Wilson, Alex. (2020) Profile of Peter Addison. Accessed at anentscottishrunning.com

I am indebted to The British Newspaper Archive for access to the following:

The Evening News; North British Daily Mail; Greenock Telegraph and Clyde Shipping Gazette; The Greenock Advertiser; The Glasgow Daily Herald and The Glasgow Herald; Evening Citizen; The Hamilton Advertiser; The Daily Review; The Evening News and Star; Falkirk Herald and Linlithgow Journal; The Dundee Advertiser; The Fife Free Press; The Ardrossan and Saltcoats Herald; The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News.

Also indebted to sources provided by Hamish M Thomson (National Union of Track Statisticians) for first clubs and first runs as well pictorial material.