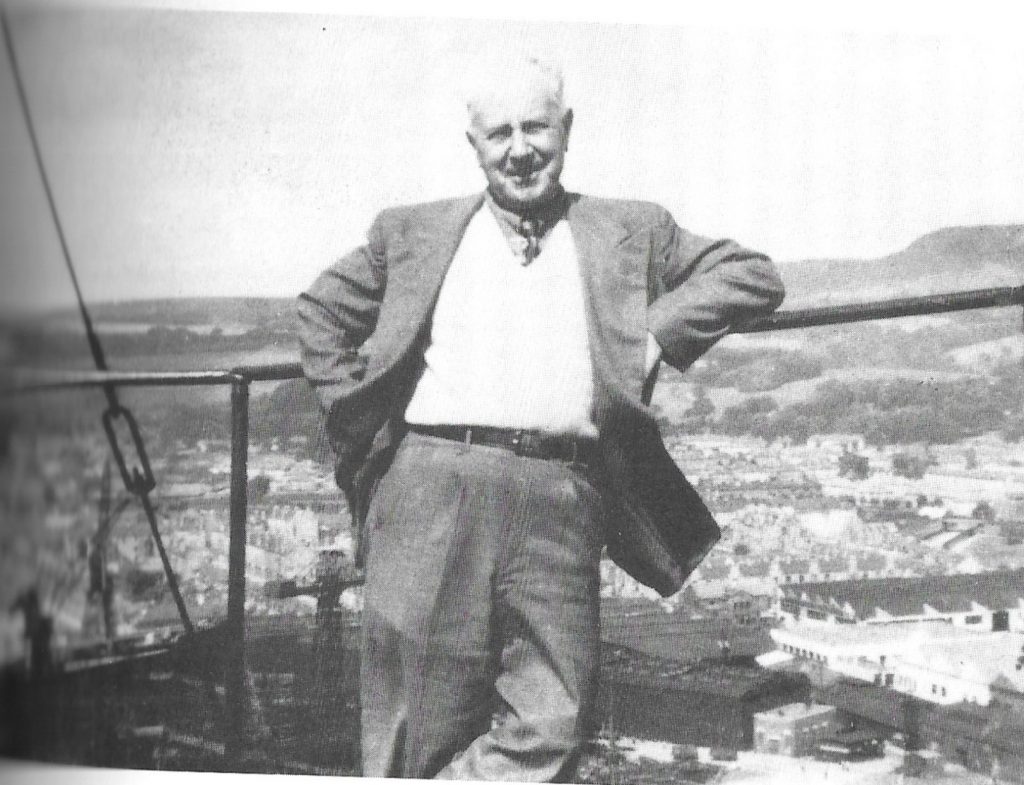

James Reston as he was in later life in the USA

Over the years many club members have emigrated and for many reasons – after the first War there were several because of the recession which was in evidence all over the world – they went mainly to the USA. After the second War, spirits were high, everybody was happy and there were many who emigrated, but this time mainly to the former Dominions of Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. James Reston was a very good athlete indeed – runner, member of many championship winning teams, club captain and committee member at the start of the twentieth century who emigrated to America in 1920. Why did he go? His son was James ‘Scotty’ Reston – a top class journalist who interviewed American Presidents from Kennedy and Nixon right through until his death in 1995. That was a massive leap for the family fortunes.

We should begin by looking at his running career, then we will look at his life away from the track.

Reston was in the main a cross country runner of some ability who first appeared in the club handbook for 1901/02. There was a J Reston from Coatbridge who ran in the National in 1900 for Coatbridge finishing eleventh, which was four places in front of the Clydesdale’s last scoring runner, in a race which was won by a single point. Reston was not a member of any of the Coatbridge teams in races in January or February of that year – not in the West District Championships nor in the Scottish Junior Championships. For the latter Coatbridge had 12 names listed in the programme with another six as reserves but none were called Reston. The Coatbridge team that day finished third with their first three runners being Andrew Forrester (2nd), Alexander J Forrester (9th) and James Reston (11th). All three were counting runners for the Clydesdale team the following year.

Reston improved dramatically over the year, if the relative positions of the Forrester brothers are any guide, and finished fourth and third scoring runner for Clydesdale Harriers. The other runners were D Mill who was first, R Reid second, A Forrester eighth, R Frew eleventh, AJ Forrester 12th. The fact that the two Forrester brothers were from Coatbridge adds to the suspicion that he was indeed the J Reston Coatbridge from the year before.

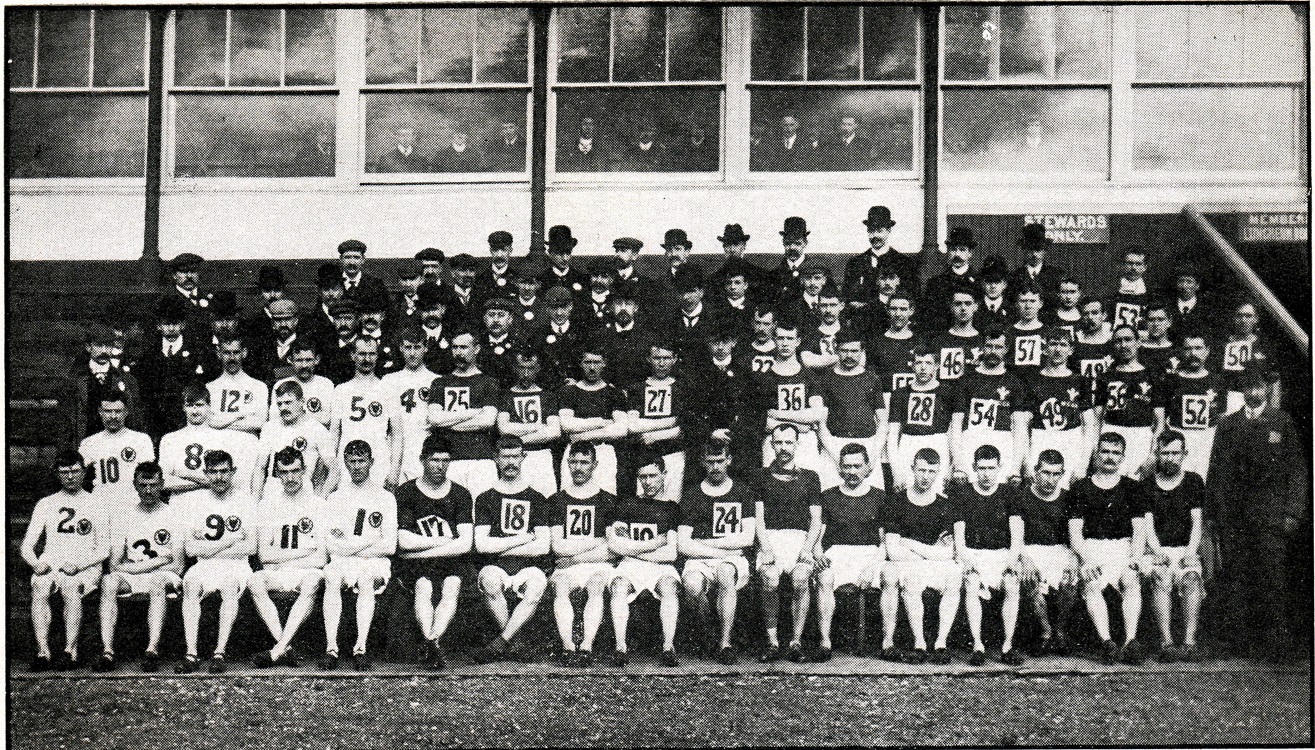

In season 1902/03 he won the prestigious Clydesdale Harriers Individual and Team Race held over 7 miles from Scotstoun in Glasgow, on 22nd November, 1902 from team mate Robert Frew with Garscube’s Samuel Kennedy third. He was again fourth in the National but this time was first scoring runner for the second placed Harriers team with the remaining scoring runners being Wilson twelfth, Frew thirteenth, A Forrester thirteenth, S Stevenson twenty fourth and AJ Forrester thirty fifth. 1903 was the first time that Reston was selected to run for Scotland in the Cross-Country International for the simple reason that it was the first ever international. It was held at Hamilton Park and contested by Scotland, England, Ireland and Wales. He finished 22nd of 41 finishers in the race and was fifth scoring runner for the third placed team.

The teams that ran in the 1903 international

He ran again for the Scottish team in 1904 after finishing third in the Scottish Championships at Scotstoun Showground. The club was again second and was led home by Sam Stevenson who would be a competitor at the Olympic Games in 1908. Stevenson had come through the ranks steadily to become a national title winner on the track as well as over the country. This time though Stevenson was second, Reston was third, Robertson seventh, Dick twenty eighth, Frew thirtieth and WG Kerr thirty eighth. The international was held at St Helen’s in Lancashire where Reston finished 20th in a field of 43 to be fourth Scottish finisher in the team that was third.

The above pages from the Clydesdale Harriers 1903/04 Handbook indicate that he had quickly become an important member of the club. He was by now – only two years into the club – Vice Captain. Each section had a section Captain and vice captain and at this time the club had the Headquarters Sections plus Airdire, and Dunbartonshire.

Below we have two more pages from the 1903/04 Handbook which have further information of this season’s work.

The next two pages of the Handbook refer to the Clydesdale Harriers 7 Miles Open Individual and Team Race held annually at Scotstoun which was one of the classics for several decades and be contested by all the clubs and runners in the country. For several years there was a sprinting competition in the Scotstoun arena with heats and semi-finals to entertain the spectators while the runners were out in the country running a two lap course round the west end of Glasgow. Prizes were often presented at a ‘smoking concert’ in the club rooms at 33 Dundas Street the following Wednesday. At times they sold tickets to the evening at 3d a ticket.

In the following extract from the same handbook, he is mentioned three times in two pages with a ‘special mention’ for his fourth place in the National.

Not only was he a talented cross-country runner – and remember that the national championships were held over ten miles of road, grass, plough with obstacles to be climbed or waded through – but a good track runner.

He also ran on the track in 1904 and at the Clydesdale Harriers Sports on 28th May at Meadowside was part of the winning two miles team race in which the first three – S Stevenson, William Robertson and James Reston – were all club members and all international athletes.

He was promoted from Vice-Captain in 1903/4 to Captain in the next (‘04/05) season with Sam Stevenson as his vice-captain. He ran in all the usual races over the country – club championships, 7 Miles Team Race at Scotstoun and the National Championships on 4th March at Scotstoun. This, 1905, was his last National Championships he was fifteenth, again behind Stevenson who was third, and in front of Martin twenty second, Campbell twenty fourth, A Forrester twenty sixth and W Robertson thirty eighth. The team was third.

*

It was at this point that Reston, who had been living in Clydebank for some time, disappeared from the scene. He is not spoken of in athletics notes, sporting papers (such as ‘The Scottish Referee’) or even the club handbook.

What do we know about him as a person? He was reported to be 5’2” tall and known as “Wee Jimmy”. This is at variance with our typical picture of a Clydesdale Harrier of the time, modelled as it was on the Gentlemen’s Club with “one black ball in three” to exclude applicants for membership. but does indicate that all were welcome in the club.

In the search for more information about his personal circumstances we will use in the main two sources:

First there is the firsthand information from the biographies of his son and his journalistic contemporaries;

Second, we will use much of the research information gathered by Hamish Telfer.

A mature Jimmy at Dumbarton Rock

All of the biographies, whether they be very short or fairly long, mention that James was a ‘devout Christian’, or that he ‘had strong Calvinist beliefs’ or a variation on that theme. They all unanimously mention that he was not a well-off man. Eg: his son was ‘born in poverty’ or ‘born into a poor Scottish Presbyterian family’. This is maybe a bit simplistic.

Johanna Reston, Jimmy’s wife.

To start at the beginning: James was born on 30th April, 1872, to Thomas and Elizabeth Reston at 4 Claythorn Street in Calton, Glasgow. Thomas was a cloth lapper by profession (ie one who moved cloth in the factory from one machine to the next in the weaving process) and by definition not a well-paid man. By 1881 they were living at 3 Glenpark Street in the Barony District of Glasgow. His father was now a van driver and James had three brothers and two sisters. They moved again and by 1891 they were living in Cardross, Dumbarton; his father was now a Warehouseman and James a ‘Dyer Markhand.’

Those who said he was ‘born in poverty’ were probably exaggerating quite a bit, but in the days when men were employed as needed by the employer and then ‘let go’, his father had to move around quite a bit to stay in employment. He started as a cloth lapper and then had two other jobs and house moves before going back to the same job in the same factory.

James met Johanna Grace Irving, a woman from Stranraer whose father was described as a master craftsman and of some means. He was a sculptor who was employed in making gravestones. She had moved to Glasgow and was a clerk at a wood merchant’s and stayed at the YWCA in Calton. James and Joanna were married on 22nd June 1903 in the United Free Church. By now they were living at 6 Radnor Street, Radnor Park, Clydebank, James’s employment was listed as Vertical Machineman. They had a daughter (Johanna junior) born in 1906 and a son (James junior) on 3rd November 1909.

We are told that. They had enough money for ‘simple food and plain clothing’ but almost nothing extra. Scarcity of money combined with a harsh code of self-denial, sacrifice and rigid religiosity imposed by his mother. He worked as a machinist in the shipyards but, typical of the time, he was employed when needed by the yards, frequently laid off with no ancillary benefits and no guarantees of full-time work. But by the census of 1901 – when James was starting to make his name as a runner – he was still living at home, but ‘home’ was now back in the Calton district where his father had returned to his trade as a cloth lapper while James was 28 years old and an ‘iron fuller’ which we are told is a practice in metal working and of moulding metal material.

Why did he stop running? By 1905 he was 33 years old which was quite old for a runner of the time and he was now also a married man with a first child due in 1906 and a job which did not pay very much and was liable to be stopped when the employer thought it necessary. This is where the first trip to America took place. By April 1911 he had gone to stay with his brother in Dayton, Ohio and try to make a better life there for himself and his family. We know that they were not at all well off when we note that he travelled ‘steerage’. Not a word known today, steerage was the lowest possible way to travel. Wikipedia tells us

“Steerage refers to the lowest possible category of long-distance steamer travel. It was available to very poor people, usually emigrants seeking a new life in the New World, chiefly North America and Australia. In many cases, these people had no financial resources and were attempting to escape destitution at home. Consequently, they needed transportation at an absolute minimum cost. In many cases they provided their own bedding and food. Steerage was very cramped and there was hardly any room for fresh air to get there. Many people died in steerage.

The term steerage was used to refer to the lowest category of accommodation, usually not including proper sleeping accommodation. In the United Kingdom, it was often referred to as third class, but there were instances where steerage was effectively fourth-class. In time, the designation came to refer to the lowest category in general, and in modern times is sometimes used sarcastically to refer to any uncomfortable accommodation in an airliner, ship or train.

Beds were often long rows of large shared bunks with straw mattresses and no bed linens.”

He made it safely to Ohio, found a job and sent for the family who came across to join him. It didn’t work. Johanna was a strict housekeeper, ran the family budget and was a very strict observer of the Christian religion as practised by the United Free Church. For whatever reason, some say Johanna fell out with her sister-in-law, it didn’t work out and they came back home.

There is a lot of discussion about this period in his life in “Scotty: James B Reston and the Rise and Fall of American Journalism” by John F Stacks. This version of the aborted emigration says that in 1911 when his son was only two years old, he went to America where he hoped life would be better. He went to Dayton, Ohio, but the ‘Independent’ tells us that domestic and financial problems overwhelmed the family’ and they returned home. Stacks book says: “Less than a year after they had finally realised their dream of moving to America, the Restons were back in Scotland, their savings gone, living in a tenement house outside Clydebank. They eventually settled in Alexandria, this time in a red stone tenement, on the banks of the River Leven. And there they remained for another decade, trapped by poverty and then by the outbreak of World War 1, their hopes for a better life shattered.”

The Valuation Roll of 1915 has a James Reston as a resident at 808 Dumbarton Road and his occupation as ‘machine-man’. This property was owned by Wiliiam Beardmore who owned shipyards around the west end of Glasgow with a well known Beardmore yard in Dalmuir, Clydebank. Hamish Telfer suggests that James may have spent the war years in a reserved occupation. In 1920, the Valuation Roll lists a James Reston, also a machine-man, living at 29 Gray Road, Bonhill, Alexandria.

More flesh is added to the statistics in Scotty Reston’s own words in his autobiography, “Deadline: a Memoir”published in 1991 when he says: “My father was a gentler sort, he was a strong, handsome little man – ‘five feet two in ma stocking feet’ he would say. At work he was called Wee Jimmy. He had golden hair and light blue eyes. He was a machinist and worked when there was work at John Brown’s shipyard, or at the Singer Sewing Machine Company, or at Beardmore’s auto factory where they made munitions for the British army during the war. In most of these jobs he was an inspector, and he took great pride in measuring things down to a hair’s breadth and he was very good at it.”

We stay with the two books to follow him on the second emigration in search of better things.

Stacks again: “Throughout the years of World War 1, and in the face of periodic unemployment and the expense of two children, the family scraped together enough for another passage out of Scotland. “How they every saved enough money on my father’s salary to get back to America, I’ll never know.” Reston said. In 1920 Jimmy Reston again went off to America. Months later Johanna, James and Joanna sailed in steerage to make another try at success. [They sailed out on the SS Mobile arriving at Ellis Island on 28th September, 1920] In New York they were immediately put into quarantine as a precaution against smallpox, and young James worked in a kitchen at the quarantine facility to, as his mother put it later, “get more food for his family”. When they finally arrived in Dayton, Ohio, Jimmy met them at the train station running happily down the platform. He had found a job and had rented space in a gloomy rooming house along the railroad tracks. The good news was that there were electric light and an indoor toilet.”

We are further told that James, and son James, at the age of 10, became paid caddies at the local Dayton golf club and young James attended the local Oakwood High School. For more information on how he went from there to become a world class journalist with friends in very high places, there is plenty on the internet.

We hear no more of James Reston the runner but the story is a familiar, if depressing, one to anyone who knows anything about the desperation of the working man in that period of Scottish history. His career as a runner was a series of triumphs with medals at every level, honourable club positions such as club captain in a club modelled on a gentleman’s club with celebrated sportsmen in a wide variety of sports, and competitor in the first two international cross-country races. His life plunged into extreme poverty and then there was the tremendous upswing in the States where he lived to see his son become a well-known, highly respected and, maybe more important to a man who had known penury, very well-off journalist, before he died of cancer at the age of 62. Unfortunately there is no record of his early career in athletics despite his son talking of him taking 15 mile walks on Carman Muir, Balloch. It would have been an opening but nothing is said of it.

Thanks are due to Hamish Telfer for the statistics used in the second half of the profile and to Allan Sharp for his help when I was starting this profile.