One of the most familiar sights at coaching conferences and conventions has been of Frank Dick’s tall, tanned and silver haired figure talking, listening, encouraging and watching everything that was going on. Nothing seems to escape his gaze. There are many now however who do not recognise either the man or his contribution to Scottish Athletics.

Many good, indeed some excellent, coaches have never been athletes themselves but Frank Dick does not come into this category. He was a talented athlete before he took up coaching but he knew all along it seems that this was what he wanted to do. As an athlete he ran for no fewer than five teams, two of them University teams – Edinburgh and Loughborough – as well as Royal High School FP, Edinburgh Southern and Octavians. Between 1960 and 1964 he set personal best times in events from 100 yards up to 880 yards as follows:

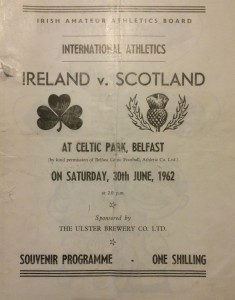

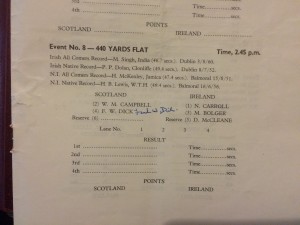

100 yards: 10.2 sec; 220 yards: 22.6; 440 yards: 49.7; 880 yards: 1:54.7; 440 yards hurdles: 55.9. In terms of competitive success, he did best in the hurdles with a second in the SAAA championships in 1962 and a third in 1963. He represented the East of Scotland v the West at 880 yards and competed in the International against Ireland in Belfast where he was second to Ming Campbell in the 440 yards. More noteworthy still, he ran for Britain in an indoor international against Finland on 18th April, 1964, at Wembley where he was third in the 440 yards in 52.0, the race being won by Nick Overhead in 50.6. He had been selected for this on the strength of his performance in the AAA’s championships at the end of March where he had finished fifth in the 600 yards in 1:13.9: Overhead was third in this race where the first two were foreign athletes. There had been no 440 yards or 400 metres in that particular championships.

Programme Cover from the 1962 International, and

the relevant programme extract

Clearly a talented runner with achievements to be proud of but it is not as a runner that he is best known or will be remembered. Frank has been a coach to individual athletes, worked at national level as Scottish National Coach and UK Director of coaching. He is a world recognised authority on coaching theory and physiology and is also known for his work on coach education. His knowledge of coaching theory, principles and practise has been used with athletes in other sports as diverse as tennis and motor racing. One of the very best Scottish coaches.

Originally from Berwick, Frank attended Loughborough in early 1960’s. He had been educated at the Royal High School in Edinburgh before moving to Loughborough where he trained as a teacher of physical education and mathematics between 1962 and 1965. At Loughborough where, as an international athlete himself, he was influenced by lecturer Geoff Gowan, later the Director of Sport Canada, and other members of the Loughborough staff. Their imagination, innovation and meticulously high standards, inspired Frank to achieve equally high standards in his work as a coach.

After graduation he went to the University of Oregon from 1965 to 68. Bill Bowerman was the coach there and this was another catalyst for Dick’s own coaching career. When he went to Oregon, sports scholarships were a rarity and Dick said, when asked how he financed the time in America gave four sources: 1. He applied for and received a Fulbright Scholarship; 2. A Churchill Scholarship provided medical insurance; 3. He worked the ‘graveyard shift’ (ie from midnight to 8.)) am) at the Georgia Pacific Sawmills; 4. He sold everything he could and used all his personal savings. Despite the graveyard shift he graduated BSC with highest honours. What did he learn from Bowerman? I quote:

“Bill taught me to understand that we could make them too complicated. The fact is coaching is more an art than a science. Of course you need to be equipped with the sciences. Bill certainly was and understood them to the level he needed to advantage the athletes he coached. But you cannot be a slave to science. No great athlete was so because of science. You must learn through experience of years how to apply such knowledge to meet the unique needs of each athlete in your charge. Whereas you are taught the science of coaching, you cannot be taught the art, this you can only learn. Bill’s approach was simply thoughtful common sense founded on relevant sciences and tempered to an art learned through life experience. The inspiration he afforded was to believe in the value of experience and your capacity to learn your own art of coaching from that.”

After he returned to Scotland he became Scottish National Coach from 1970 to 1979 after John Anderson moved on to a post in England. As National Coach he was very different from John in style but they both had a firm belief in the importance of coach education. John had started an annual international coaching convention held in Edinburgh, Frank continued it and developed the idea making it much more of an international event with Scottish coaches being exposed to the newest information presented by top level coaches, scientists, physiologists and athletes. I attended several of these and remember the occasion when a distinguished Swedish sprinter was asked why he had changed his coach so often. His response was that he had had five coaches in his career and had learned from all of them “but”, he added, “you coaches must remember that it is the athlete that makes the coach famous, and not the other way round.” It was at one of these that I first heard Frank say that the athlete should never be restricted by the coach’s limitations. They seem obvious now but they both provoked a lot of discussion at the actual time. The coaching structure in Scotland was simple and very effective – a national coach who was paid, group coaches for the four main disciplines of sprinting, endurance, the jumps and the throws. They were responsible to the national coach and appointed their own staff coaches for each event in their group. They were accessible to coaches at club level who went as far through the education system as they were able or felt they needed to go. There was the basic Assistant Club Coach which was a broad course with all events covered, followed by the Club Coach which was where event specific work was being tackled for the first time and then the Senior Coach award topped the qualifications available. It was straightforward and was available at very little cost to the coach. Frank himself was also in touch with the grass roots of the sport – for example he had monthly meetings alternating between Edinburgh and Glasgow on a monthly available to all coaches who were coaching athletes of District Championship standard or higher. I attended these and was in the company of such as Alex Naylor, Eddie Taylor, Sandy Robertson, Gordon Cain and many other top quality coaches. This was Frank speaking and talking to club coaches, maybe 20 at a meeting, where they had the opportunity to speak to him in a small group. He not only raised the standard of coaching and numbers of qualified coaches in the country, he raised the profile of coaching higher than it had ever been.

Popular with athlete and coach alike, he was coach at the 1970 Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh and the mascot was a huge teddy bear, decked out in Scotland kit, called Dunky Dick – Dunky for the team commander Dunky Wright and Dick for Frank as head coach. They were the most successful Games that Scotland had ever had and it was a wonderful start to his career as National Coach.

He became UK Director of Coaching in 1979, a post he held for an incredible 15 years, to 1994. It was during this period that the Great Britain and Northern Ireland athletics team rose to become a real power in world athletics, led in particular by male track stars such as Sebastian Coe, Steve Ovett, Steve Cram, and Dave Moorcroft, in addition to the double-Olympic decathlon champion Daley Thompson. Frank was always a ‘hands-on’ coach and Daley was ne of his top athletes – coached by Frank he rose to become one of the world’s greatest ever athletes. Like Tom Macnab, Frank wrote a lot during this period and his influence as a coach was increased and enhanced by it. In 1980, his book Sports Training Principles was first published and this has become a classic multidisciplinary text and was considered ahead of its time in applying science to sport. In addition,Frank has been Chair of the British Association of National Coaches, Chair of the British Institute of Sports Coaches, and was appointed President of the European Athletics Coaches Association.

In 1989 he was awarded the BE for services to sport. In 1998, he was inducted into the UK Coaches Hall of Fame and was presented with the prestigious Geoffrey Dyson award.

Given that the British team was more successful than it had ever been why did Frank Dick leave in 1994? In essence he quit in protest after his coaching budged was halved. He has gone on record to say that the decline in performance had begun before he left, but there are few who would now dispute that his departure was a serious blow to the sport. Success always produces a variety of reactions in its beholders. At the time there were those who said it was his loss, not athletics’. That, having cut himself off from track and field, he had lost his purpose. That the charge had no substance was seen as he went on to be one of the most sought-after motivational speakers in the world, inspiring audiences far outside athletics with his insistence that, given the right conditions, we are all capable of success. Many of his phrases have come into the lexicon – phrases such as the ‘Valley People’ and the ‘Mountain People.’

He is still working in that capacity – he’d be silly not to – also made a partial return to athletics when he agreed to become chair of Scottish Athletics. It was an honorary post, officially requiring a commitment of no more than a day a month. To be done properly, however, he thought it needed work for several hours a day. Although born and raised in North Berwick, he had been living for decades just outside London and had to travel up to Scotland to carry out his duties in connection with this post. His resignation caused more than a slight fluttering in the dovecotes of Scottish athletics. Doug Gillon picked the issue up and as usual covered the whole thing fairly and in a bit of detail in his article of 22nd February 2012.

“FRANK DICK stepped down yesterday as chair of scottishathletics, with the ink barely dry on a strategy document which was his brainchild and several posts linked to it still waiting to be filled. The precipitate departure of this perceived white knight – former Scotland and UK national coach from the sport’s golden era – makes it hard to avoid the conclusion that this is now a sport in crisis.

A perception that if Dick could not improve the sport’s performance profile then nobody could is calculated to haunt successors. The departure coincided with the unveiling of a 39-strong GB team for the World Indoor Championships without a single Scot. That’s not calculated to boost optimism.

Dick’s public valedictory comments struck predictable chords: “It’s been an honour . . . I firmly believe we’ve achieved a great deal . . . Our sport is stronger than it has been for some years … The challenge is to continue that progression as we approach the Commonwealth Games in Glasgow . . . As I pass the baton, I wish our athletes at all levels every success.”

Privately, there was a discordant note. We have frequently discussed his frustration with lack of progress. The reason for his resignation was, he said: “Sheer geographic distance [between his London home and Scotland]. It was a headache for me to be as effective as I should be. Modern technology was not able to counter the geographic distance in terms of day-to-day leadership.” He was told this honorary unpaid job would take “about one day per month. In fact it has averaged three hours a day”.

In the professional structure of Scottish sport – within and outwith the governing body – some will be glad he has gone, however. They have told me so privately on pain of confidentiality. They cite Dick’s alleged over-close scrutiny contributing to the departure, after barely a year, of national coach Laurier Primeau, and of friction between Dick and Primeau’s interim successor, Steve Rippon, now also departed. A third head coach is now sought in little over a year, with Dick, most experienced in such appointments, now also gone. These staff departures prompted a major scottishathletics strategy review in which Dick proposed appointing a full-time director of coaching, athlete pathway and talent manager, and performance programmes manager. All remain pending.

There seemed sorrow in Dick’s voice as he spoke of resignation: “Probably I belong to another era, and it’s important the sport is given something positive to move on. “I don’t want the sport to bruise more than it has. It’s the right decision for everybody. There are all sorts of pressures in my life and for scottishathletics. They need somebody there in a greater presence. I like to be involved, but could not be involved at that distance.

“Some great kids at the moment around Scotland will be in with more of a shout than people thought come 2014, and some really good news coming on performance. These are stories for the future. I am a story of the past. Appointments will be made in the near future, which is great. And every good wish to my successor.”

Despite his protestations, I can’t help feeling Dick leaves almost exactly 42 years after his appointment as Scottish national coach, with unfinished business –and several records set in 1970 still standing. “Some quite rightly stand the test of time because they were good records,” he said, “but others really should have gone by now. We did drop back, but we do have people who will challenege, I think, for medals – plural – in 2014. It’s unfortunate that I can’t take the next step with them.”

The abrupt nature of his departure, and recent criticism and innuendo prompts me to explore whether Dick was levered out. “Not at all,” said the scottishathletics chief executive, Nigel Holl. “We are making very good progress with the appointment of the performance team and Frank has been central in both the design of the new structure and the interviews we have held. His input has been pivotal. There is no crisis. I think he has helped get us into a much stronger position. We are very grateful and are sorry he has stepped down.”

Born in 1942, Frank is now 72 and it is unfortunate that he has apparently ended his career with Scottish athletics on a controversial note. He did so much for us as a country in the 1970’s while National Coach, continued to help Scots coaches and athletes while British Director of Coaching, brought and contributed to conferences and conventions to Glasgow and has generally been an influential figure in Scottish athletics for half a century and we owe him.

We have mentioned his motivational speaking and his involvement in coach education – have a look at him in action in these youtube clips:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aMPziod-Fx4

However you don’t have a successful career like Frank’s without attracting some criticism. I quote from another very successful British coach:

“I would have to discriminate carefully between his value as a lecturer and conference speaker – which constitutes his real talent and his contribution to the sport, and any contribution he made to producing and developing athletes. Plagiarism is the biggest contribution he offered athlete coaches – at least that was the word in academic circles where these overlapped with those of athletics itself. He provided us all with some of the “secrets” of our East German friends in that way.

For all his experience and knowledge, I did not see Frank as the kind of coach who developed an athlete over time to his full potential. His generation of coaches at national level were appropriate for a period in which development came from the athletes and club practices themselves from a strong physical development and hunger. As a Coach he was no doubt talented in providing the psychological advice and preparation for competition. I don’t want to denigrate him or the value of this aspect of coaching but it was not something that had a primary significance in the nineties and later. Nevertheless, as we all have experienced, he was a charismatic figure and one who galvanised conference audiences within the sport and no doubt a lucrative career outwith it.”