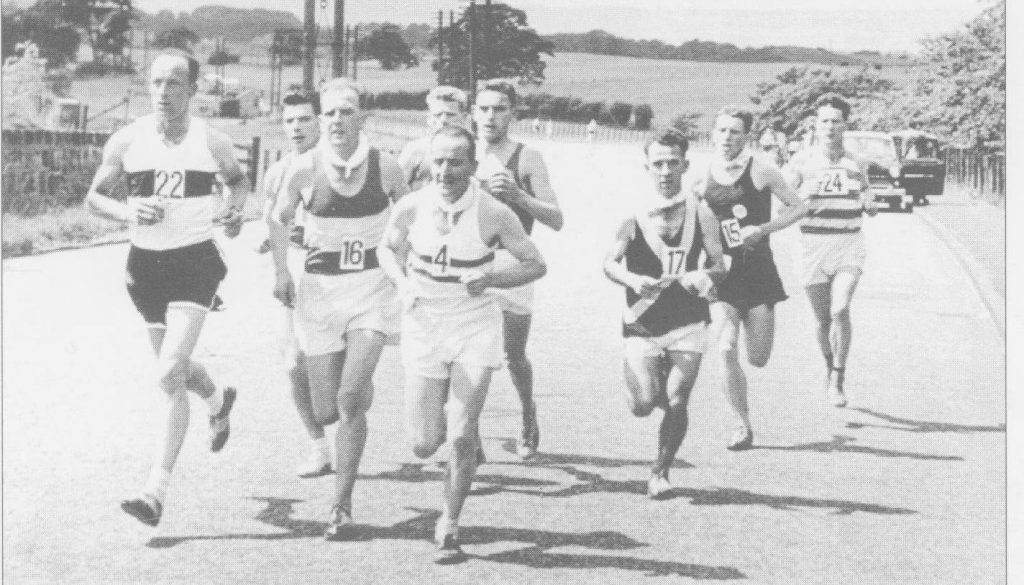

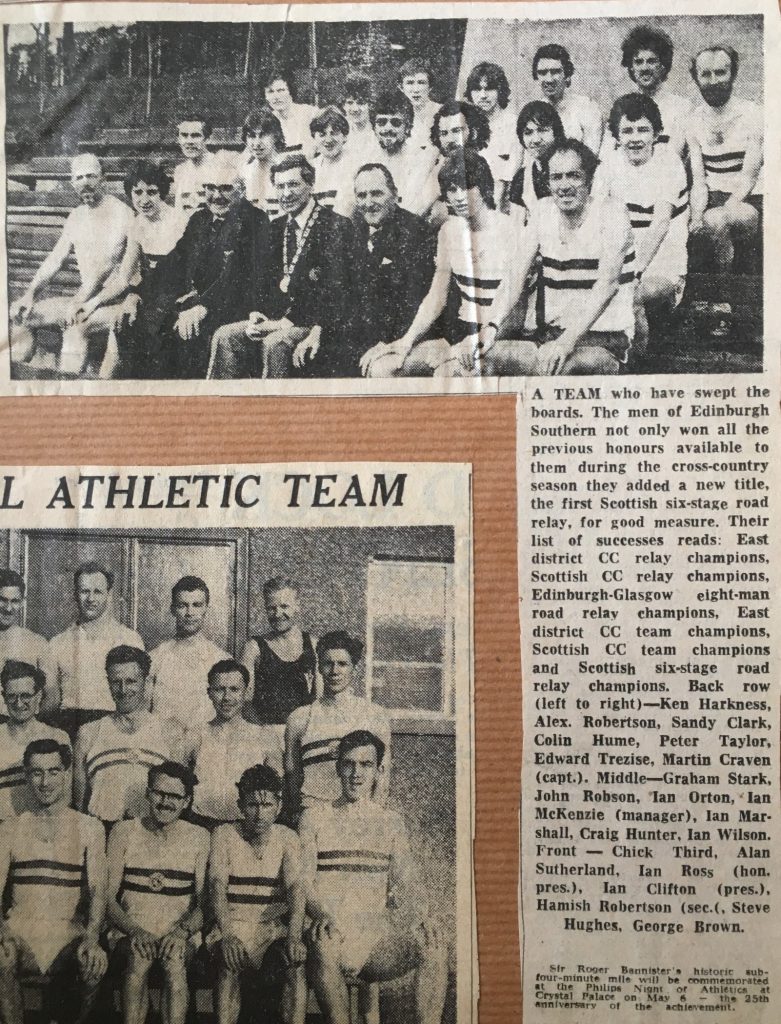

Pamela winning the road race at Cartha

Pamela McCrossan came late to the sport and has done so much, and so well, that we wonder what she might have achieved had she begun running earlier. She concentrated on road and country although she did take part in some veteran’s track races, and also turned out for the club in the league. She finished first W55 in the 2018 Scottish Cross-Country championships; and has run for Scottish Masters eight times in the British and Irish Masters Cross-Country Championships.

Pamela has completed the questionnaire for us as a start to an in-depth look at her running career.

NAME Pamela McCrossan

CLUBs Clydesdale Harriers and SVHC

DATE OF BIRTH 10/6/1961

OCCUPATION Theatre Charge Nurse (now retired)

HOW DID YOU GET INVOLVED IN THE SPORT? Cliff Brown is a neighbour of mine. He was a runner and a member of Clydesdale. He encouraged me to do a Ladies 10k race one year (about 24 years ago) and he helped me train for it. He then persuaded me to join Clydesdale Harriers and I have been running and racing ever since.

HAS ANY INDIVIDUAL OR GROUP HAD A MARKED INFLUENCE ON YOUR ATTITUDE OR INDIVIDUAL PERFORMANCE? Clydesdale Harriers have had a huge influence on my running and helped me improve over the years. I have received so much help, support and encouragement from everyone there and I have made many good friends. Now I am very proud to be an Honorary Member of the club and to have in the past been Ladies’ Captain.

WHAT EXACTLY DO YOU GET OUT OF THE SPORT? So many things! It keeps me fit and healthy and I get to enjoy the pre and post-race banter and chat with other runners. I often get to meet new people when I race or do parkruns and I get a great sense of achievement after a good race or a hard training session. I also get to spend time with like-minded people and fellow runners who are always so friendly.

WHAT DO YOU CONSIDER TO BE YOUR BEST EVER PERFORMANCE OR PERFORMANCES? That’s a difficult question as I have done so many races over the years. However I was totally surprised and delighted to finish as first lady in the Aberfeldy Marathon in 2012 at my first attempt at the distance. I have also been lucky enough to be part of a medal winning team on the eight occasions I have represented Scotland at the Masters International British and Irish Cross-Country events.

AND YOUR WORST? A Dunbartonshire cross country race many years ago when I went over on my ankle and had to be carried off the course by John Hanratty! I then had to go to the Western Infirmary as a fractured ankle was suspected (it was actually ligament damage) and I had to take time off work. The only race yet where I have been a DNF.

WHAT UNFULFILLED AMBITIONS DO YOU HAVE? None really. At my age I consider myself very fortunate just to be able to run and still compete in races.

OTHER LEISURE ACTIVITIES? I go to classes in the gym, go to the theatre and cinema and I like to go on holiday as often as possible! First thing I pack is the running gear! I also do a lot of walking.

WHAT DOES RUNNING BRING YOU THAT YOU WOULD NOT HAVE WANTED TO MISS? Running has brought me the opportunity to represent Scotland and the chance to spend many wonderful running holidays in the Canary Islands with friends from Clydesdale and other clubs. I have also enjoyed many weekends travelling away for races and special social occasions with friends I have met through running. These are just a few things I would not have wanted to miss.

CAN YOU GIVE SOME DETAILS OF YOUR TRAINING? I try to run 4 or 5 times a week and do different types of sessions. There may be a speed session, a steady run, a hill session, a long run and maybe a parkrun too. I also like to do some classes in the gym for cross training.

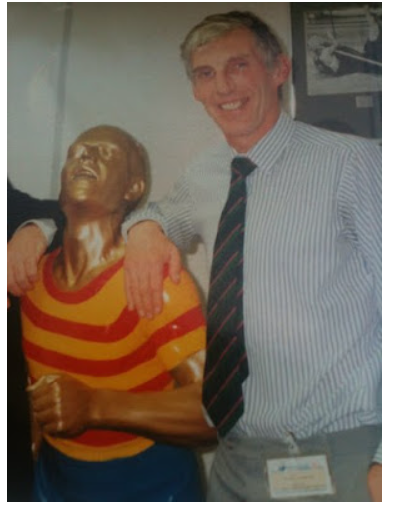

Pamela Running in the West District Championship

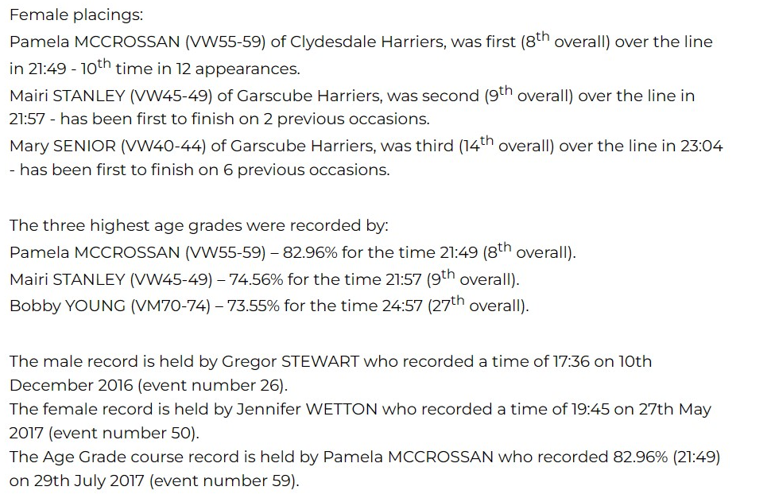

The replies above are very interesting so we asked her to elaborate on them. She tells us that her very first race was one of the annual charity 5k Races for Life in Glasgow with work colleagues before she was ever an actual runner. She says, “I hadn’t trained at all. I ran and walked where I had to and really enjoyed it , maybe that’s where my love of running really started! However, I was always fairly fit with dog walking and aerobic classes, step classes etc.”

As for her family background and sports before taking that first step into competitive running she says: “I have no family history whatsoever of running and I never ran competitively at school at all. I did play in the hockey and netball teams without any great success.“ She adds: “My first race after getting to know Cliff was the Ladies 10k in Glasgow. He set up a small group for women to train specifically for this. This must have been around late 1990s.”

I then joined Clydesdale and my times gradually improved until I was fast enough to pick up some prizes. Some races I did win as first lady I can remember are Stranraer 10k 2 years in a row, Erskine Bridge 10k, Bearsden and Milngavie 10k, East Kilbride 10k , Monklands half marathon, ( twice I think ) , Bute Highland games 10k, Aberfeldy marathon 2012, Kirkintilloch 12.5k . I have also won Vets races over the years too eg Bathgate Hill race. In many other races where I did not finish first overall I was top 3 or first in age group eg 2nd in Mull half (2014 ) and 3rd Lochaber marathon. (2014)”

Pamela came to the sport relatively late and it is impossible not to wonder how well she would have run had she started running earlier. That she is a very good runner is in no doubt at all and it only takes a look at some of her racing statistics to see that. She is a prolific racer – in the 19 years since 2004 she has run at least 445 races; ie: these are only the ones that Power of 10 know about! Although she is known as a road and cross country runner she is a prolific racer and has some very good track races to her credit. Some statistical information, not all of it because it would be overwhelming, about her career is illuminating. We can start with a look at her personal best times in the table below table below for evidence the quality of her running.

| Event |

Date |

Venue |

Time |

Age Group |

| 800m |

4 Aug 2013 |

Kilmarnock |

2:56.5 |

V50 |

| 3000m |

24 June 2012 |

Dunfermline |

11:49.71 |

V50 |

| 5000m |

28 July 2017 |

Glasgow |

20:12.87 |

V55 |

| 10000m |

17 Oct 2010 |

Coatbridge |

40:39.7 |

V45 |

| 5K |

27 June 2012 |

Glasgow |

19:19 |

V50 |

| Parkrun |

29 Aug 2015 |

Victoria Pk |

19:37 |

V50 |

| 7K |

15 Aug 2007 |

Bishopbriggs |

28:26 |

V45 |

| 8K |

3 Aug 2015 |

Lochwinnoch |

32:53 |

V50 |

| 5 Miles |

8 Nov 2008 |

Garscube |

31:48 |

V45 |

| 10K |

29 Nov 2008 |

East Kilbride |

38:55 |

V45 |

| 10 Miles |

15 Nov 2008 |

Brampton |

64:37a |

V45 |

| Half Marathon |

7 Sept 2008 |

Glasgow |

87:16 |

V45 |

| Marathon |

6 April 2014 |

Fort William |

3:23:47 |

V50 |

These are quite excellent times at 13 different events on three different surfaces. As a V45, 2008 was when she set most pb’s with 5 miles in Glasgow on 8th November, 10 miles on 15th November at Brampton, 10K on 29th November at East Kilbride having set her Half Marathon pb on 7th September in Glasgow. The week before the purple patch of three pb’s in November she had run 40:07 for the 10K in Stranraer where she had been first Lady.

How about frequency of racing? Have a look here:

| Year |

Category |

Road |

Track |

Cross-country |

Other |

Total |

| 2019 |

V55 |

33 |

– |

8 |

1 |

42 |

|

2018

|

V55 |

29 |

1 |

7 |

– |

37

|

| 2017 |

V55 |

29 |

1 |

5 |

– |

35 |

| 2016 |

V50 |

37 |

1 |

6 |

– |

44 |

| 2015 |

V50 |

26 |

– |

8 |

– |

34 |

| 2014 |

V50 |

30 |

– |

2 |

– |

32

|

| 2013 |

V50 |

15 |

2 |

8 |

– |

25

|

|

2012

|

V50 |

20 |

2 |

7 |

– |

29 |

| 2011 |

V45 |

20 |

– |

2 |

– |

22 |

| 2010 |

V45 |

20 |

1 |

2 |

– |

23 |

| 2009 |

V45 |

8 |

– |

2 |

– |

10 |

| 2008 |

V45 |

29 |

– |

2 |

– |

31 |

| 2007 |

V45 |

18 |

– |

– |

– |

18 |

| 2006 |

V40 |

8 |

– |

– |

– |

8 |

| 2005 |

V40 |

12 |

– |

– |

– |

12 |

| 2004 |

V40 |

6 |

– |

– |

– |

6 |

Remember that these are only the races that appear on the Power of 10 website and she undoubtedly ran more than that in total. Of course, many athletes run lots of races, but low key races, or only races near home that don’t require a lot of travel, or races that pose no challenge or even turn out in races but don’t race them, merely run round the course enjoying the company and the scenery. That does not seem to be Pamela.

Her first run in the National Cross Country Championship was in 2007 when she finished 73rd but given that there were no age categories in that event we get a better picture when we look at her appearances in the National Masters Championships between 2010 and 2019.

| Year |

O/all |

Category |

Place |

|

Year |

O/all |

Category |

Place |

| 2009 |

15th |

W45 |

5th |

|

2015 |

20th |

W50 |

4th |

| 2010 |

18th |

W45 |

5th |

|

2016 |

20th |

W50 |

6th |

| 2011 |

DNR |

|

|

|

2017 |

DNR |

|

|

| 2012 |

DNR |

|

|

|

2018 |

23rd |

W55 |

1st |

| 2013 |

13th |

W50 |

2nd |

|

2019 |

23rd |

W55 |

3rd |

| 2014 |

29th |

W50 |

8th |

|

No |

Race |

Held |

|

Not at all a bad record with the lowest age group placing 8th. Note too that it is normal for a runner to drop a place or two as they go through the years – they get older and new ‘young’ ones come into the category.

Pamela has run in many of the classics such as the Tom Scott 10 Miles in Motherwell (best time (66:24), the Brampton to Carlisle 10 Miles in the north of England (best time 64:37), Balloch to Clydebank (half marathon), Nigel Barge Road Race (5 Miles), Glasgow University Road Race, Springburn Cup Road Race (10K) as well as marathons from Lochaber in the north of Scotland to London in the south of England. Not averse to travelling nor to facing a challenge then. Pamela has also been highly ranked in the RunBritain Rankings which is open to thousands of runners from all over the country. Her best rankings, ie top ten in the UK, have been the following.

| Event |

Age Group |

Year |

Rank |

| 5000m |

V55 |

2017 |

3 |

| 10000m |

V45 |

2010 |

5 |

| 10000m |

V50 |

2012 |

4 |

| 10000m |

V50 |

2013 |

4 |

| 10000m |

V55 |

2016 |

2 |

| 10000m |

V55 |

2018 |

3 |

| 5K |

V50 |

2012 |

5 |

| 5K |

V55 |

2016 |

6 |

| 5K |

V55 |

2017 |

6 |

| 5 Miles |

V55 |

2019 |

4 |

| 10K |

V55 |

2018 |

9 |

| 10 Miles |

V45 |

2008 |

9 |

| 10 Miles |

V55 |

2019 |

3 |

| Half Marathon |

V50 |

2011 |

9 |

| Half Marathon |

V50 |

2012 |

9 |

| Half Marathon |

V55 |

2016 |

9 |

Her best marathon ranking in Britain was 22nd in 2012 as a V50.

Pamela’s progress in individual races at the start of the century has been steady. She ran regularly in the Balloch to Clydebank Half marathon between 2004 (W 40) to 2019 (W 55):

*2004 – 95:38; 2007 – 92:14; 2008 – 89:24; 2009: 89:10; 2010 – 88:11; 2011 – 90:41 (W50). There was a gap in her appearances at that point and her next race was as a W55 in 2019 when she recorded 91:57.

While the Balloch (like the Dunky Wright, all the races in the Polaroid 10K series, etc) was a home race, she also showed the willingness to travel to races – that has also been a feature of her running.

*The Brampton to Carlisle 10 miles race was run in 2004 (65:49, 11th Lady); 2005 (66:31, 3rd V); 2006 (67:13, 16th Lady); 2008 (64:37, 1st V45)

*2011 The Blackpool Hilton Half Marathon (89:48 3rd Lady )

*2014 The Isle of Mull Half Marathon (90:31, 2nd Lady, 1st Vet)

*The Isle of Man Half Marathon 2019 (97:55, 3rd Lady, 1st V45)

* 2016 Islay Half Marathon (5th lady, 1:38:12)

She even travelled for marathon races:-

*2012 Aberfeldy (3 hours 24 min – first marathon and first lady)

*2013 London Marathon (3:28:55)

*2014 Lochaber Marathon (3:23:47, 3rd Lady, 1st V50, 1st SVHC)

*2015 The Baxter’s Loch Ness Marathon (March 3:31:41)

*2015 The Greater Manchester Marathon (April 3:27:15) NB: Short

And there are other examples of this trait.

The willingness to travel to races that she felt she needed reminds us of Ian Stewart’s comments to some of his rivals – “I’ll travel 200 miles to get into a good race, you’ll travel 200 miles to get out of one.” Pamela is definitely in the former camp.

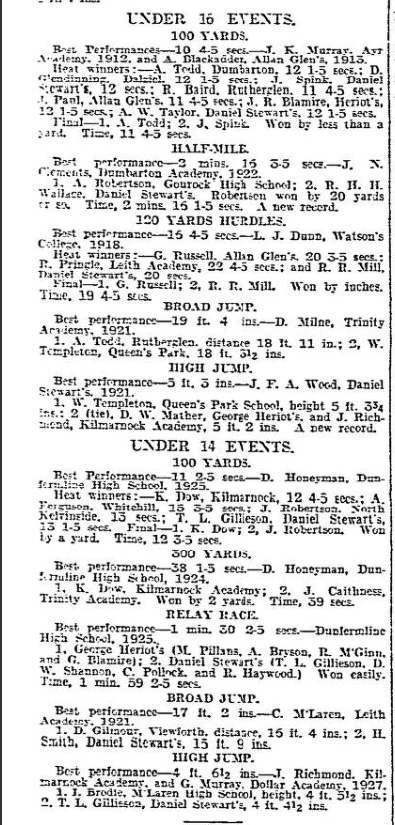

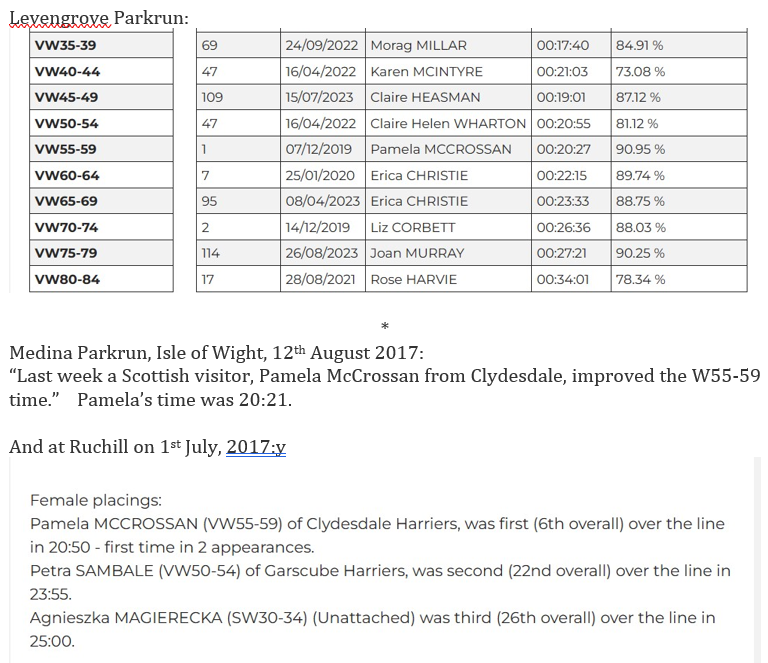

Then there are the parkruns. The parkrun is a wonderful development for the sport. They are all over 5K, they are free to run in, they are well staffed by volunteers and the times given out are accurate. All attractive features for any runner, for the really ambitious trying to better their time, and for the new runners just wanting to get round They all have their different challenges eg Drumchapel, Tollcross and Pollok are hilly and times are approximately two minutes slower, even for the faster runners than on some other courses.. Held all over Britain they are popular events. Needless to say, Pamela has done her share of runs in parkruns all over the country and also needless to say has been first across the line in some, set records in some, run personal bests, set course records and had a lot of pleasure in just being part of the scene.

She has run in these events, since 2014 according to Power of 10, in Victoria Park, Greenock, Springburn, Pollok, Tollcross, Drumchapel, Linwood, Eglinton, Ruchill, Levengrove, Jersey, Nobles Parkrun in Isle of Man, Blackpool, Bolton and Erskine Waterfront. What immediately jumps out is the wide geographical spread of the event despite the obvious preponderance in the West of Scotland. Jersey in the Channel Islands, the Isle of Man, in the south of England, Blackpool in the north of England, Glasgow, Renfrewshire and Lanarkshire. And she has done well competitively in them. It would be almost impossible to reproduce all her Press cuttings, but some of them are noted below. She did run a lot of these runs which is of interest for several reasons eg. Being relatively short compared to her usual racing distances, they were useful speed training sessions as well as runs in their own right. How many did she run? So far she has run 142 and holds V60 records for Drumchapel, Tollcross and Erskine as well as some age group records for other such runs. Here, for example is the list from 2017 as listed in Power of 10:

22 races at six venues spread between Glasgow and the Channel Islands and look also at the consistency of the times run.

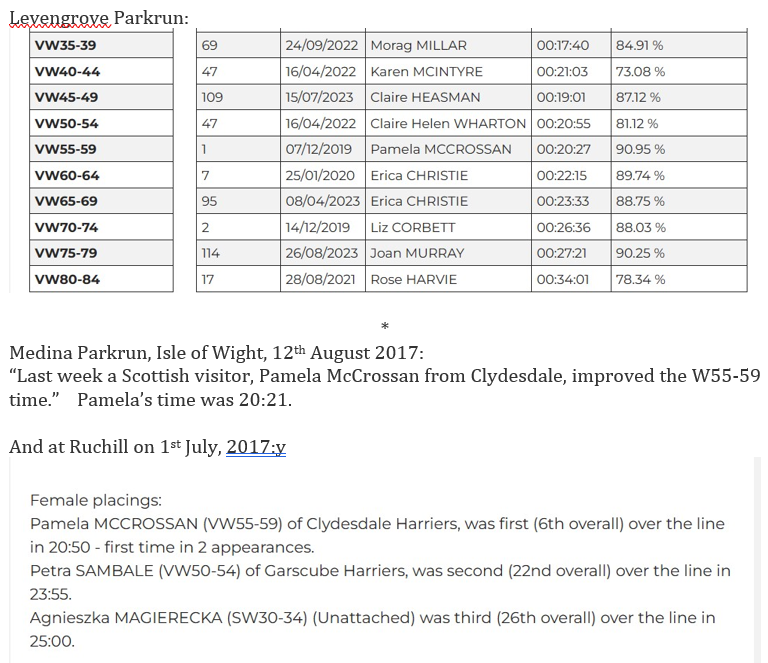

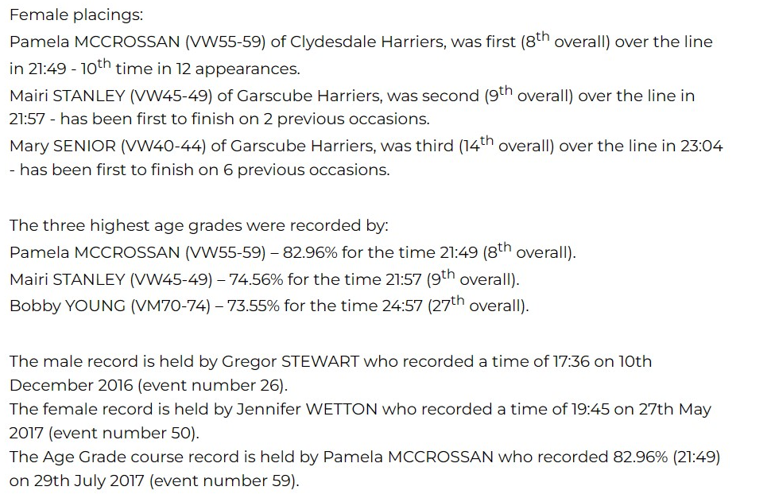

A few comments on her running in them on reports chosen at random from many more:

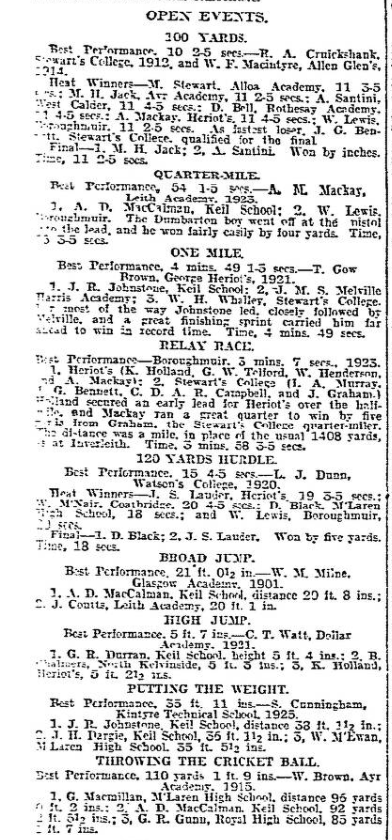

“Drumchapel, Event Number 59, 29/07/2017:

*

Linwood: The female course record is held by Jennifer Wetton who ran a time of 16:55 on 29th October 2016. The Male Record is held by Jack Arnold who ran a time of 16:16 on 20th August 2016. The age grade course record is held by Pamela McCrossan who recorded 20:23 on 13th August 2016.

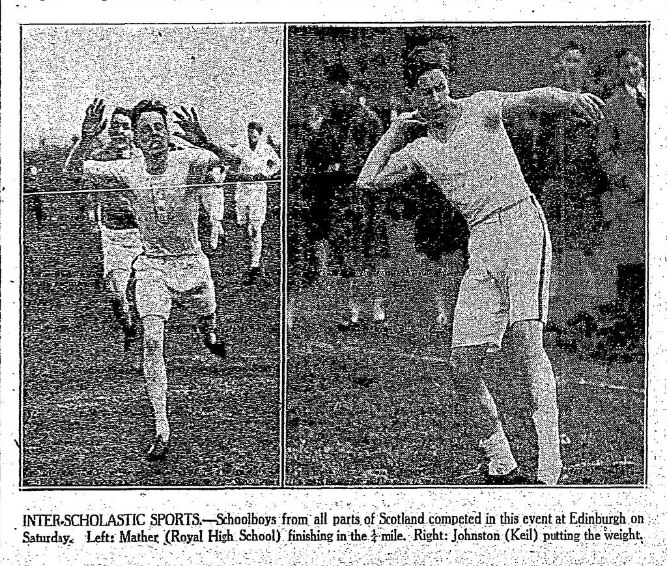

And finally at Bolton:

“The first lady to finish was Pamela McCrossan of Clydesdale Harriers who was running for the first time at Bolton in her 45th Parkrun. One of our regulars Olivia Kearney of Bolton United Harriers chased her all the way to the finish and was 22 seconds behind her at the end. This gave Olivia a Personal Best time of 22:30 which was 7 seconds quicker than she ran a fortnight ago, and this was her 195th time running at Bolton.

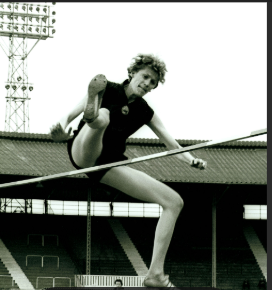

Pamela in Bolton

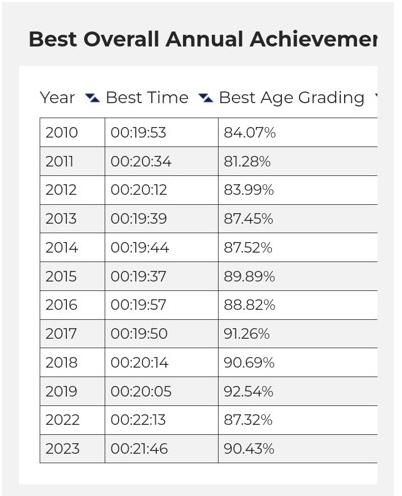

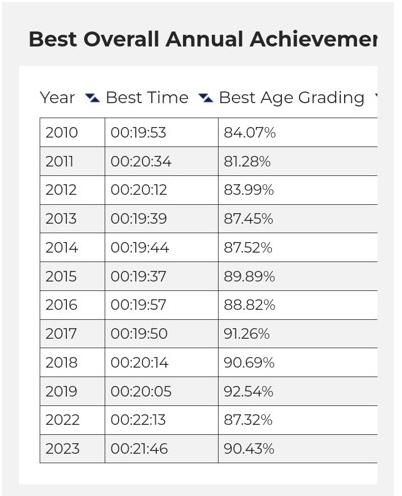

Have a look at her best annual parkruns as a measure of consistency.

The Scottish women that Pamela has been racing with and against during this period have been of a high standard. Note that in her category alone there have been such as Fiona Matheson of Falkirk Victoria, Rhona Anderson of Dunbar, Sonia Armitage of Aberdeen, and Hazel Dean of Central.

Speaking in early October 2023, Pamela says: “I only started back at the track 9 weeks ago. Hadn’t paid to enter a race since end of 2019 due to Covid in 2020 and a variety of injuries in 2021 plus part of 2022. Started back doing some parkruns in August 2022 and have kept them up. Tried the selection race for Masters International a few weeks ago and was very surprised to finish second in my age group so was automatically selected for Scotland team in November. Was delighted to say the least. That has given me an incentive to do some proper training. “ She did run in the Vets International on 11th November in Glasgow where she finished twelfth and part of the bronze medal winning team, the others being Fiona Matheson who won the race and Hilary Ritchie in ninth.

What training did she do when she was running well? In 2008 when she had her wonderful 3 personal best times in the one month, she was doing five runs a week – Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Sunday. Sunday, as for all distance runners, was the long run of usually 13 – 15 miles, Monday and Wednesday were steady runs, Tuesday reps in the Business Park (ie flat, good surface), Thursday either long reps on grass or another steady run. Fairly typical week for most endurance runners – two ‘effort sessions’, one long run and steady running the rest of the time. It certainly worked for Pamela. There were gym sessions, exercise bikes, cross-training and other endurance related activities but the running was the main thing and followed a pattern.

One of the hardest weeks was the week ending 9th October:-

Monday: 9.12 miles

Tuesday: 8 x 800 in 2:56, 2:55, 2:54, 2:52, 2:56, 2:56, 2:55, 2:53 8.5 m in total

Wednesday: 4 miles

Thursday: 5.2 miles in 38 minutes

Friday : Rest

Saturday: Glasgow University Road Race: 31:48 pb Total distance 7 mls

Sunday: 13.3 miles 1:40:24

How had the training developed ten years later, in 2018? If we take the October/November period, we see that in the week ending 11th November she had done six days training. Not all running. She summarised the week as 5 runs, 2 races and 2 gym classes. The gym sessions were a Spin Class and Body Pump on Monday; the training sessions were a hill session on the Tuesday, 6.3 miles in 48:44 minutes on Wednesday, a varied session on the golf course on Thursday, a short course championship at Lanark with warm up/cool down on Saturday, the Jimmy Irvine 10K on the Sunday. A varied week with a total of over 30 miles – but given the variety the total mileage is almost irrelevant. There were harder weeks in the course of the year. Eg, week ending 8th July:-

Monday :Spin Class 45 minutes + Body Pump 1 hour

Tuesday: 6 laps of the Business Park – 3 medium, 3 small, 3 medium 6.1 miles

Wednesday: 6 miles in 45.01 minutes

Thursday: Body Pump 1 hour + Kettlebells 30 minutes + running reps of 10 x 2 minutes to a total of 6.57 miles

Friday: Rest

Saturday: Drumchapel Parkrun – Total Distance 4.57 miles

Sunday: Long Run 15.0 miles in 2:04.45

The difference is very noticeable. More miles, harder runs and more varied gym work for cross-training + variety and all endurance based. The results are clear to see: continuing to train hard, more success and genuine enthusiasm for the sport as she advances through the age groups.

We do not know what the future holds for Pamela but her enthusiasm burns as brightly.

There are more pictures at Pamela’s Gallery – go here