Next: North of Scotland AAA

Fifty, or even forty, years ago amateur athletics practically did not exist in the Scottish Borders. Between Edinburgh, Berwick and Carlisle, the triangle that roughly includes the territory now administered by the SBAAA, not a single amateur athletics meeting was held; professionalism had the field to itself. Annual Games were, and still are, held in most of the towns and villages in the Borders, but it was only the pervading holiday spirit and fun of the fair that made some of them tolerable. The presence of the bookmakers shouting their cramped odds, and the fact that a few shillings might sway the result of a race, did not tend to hold the interest of the looker-on; nevertheless, these games were the only outlet for the budding aspirations of the young athlete, and whatever his first ambitions for athletic glory might be, they were likely to become subordinate to the sordid considerations of £.s.d. Many resented this, but in the total absence of amateur meetings they were helpless and drifted into the porfessional ranks.

Therefore, in 1895, when Mr DS Duncan first cast his eyes on the Borders as a prospective field, the ground was really ripe for some amateur effort. What perhaps was at the back of the enthusiastic Secretary’s mind, as well as spreading the amateur gospel, was the strengthening of his own Association, between whom and the seceding body, the SAAU, the quarrel was now at its height.

A small circumstance had also some significance in directing Mr Duncan’s gaze to the Borders. In that same year, 1895, there was formed in Innerleithen an athletic club under the title of “The Scottish Pelicans”. This club included in its limited membership several names still familiar in the Borders, W Lindsay Watson, Tom Scott (Langholm), JK Ballantyne, and last, but not least, AR Downer. It is not generally known that Downer spent a great deal of his boyhood on the banks of the Tweed, and that his first races were run on Caberstone Haugh against the boys of Walkerburn School.

The meeting at which the SBAAA was formed was held in the Tower Hotel, Hawick, on Saturday, 18th January 1896. Mr Duncan himself took the chair, and successfully launched the new venture. There was a fair attendance, and several of those present did yeoman service for the cause in the early days of the Association.

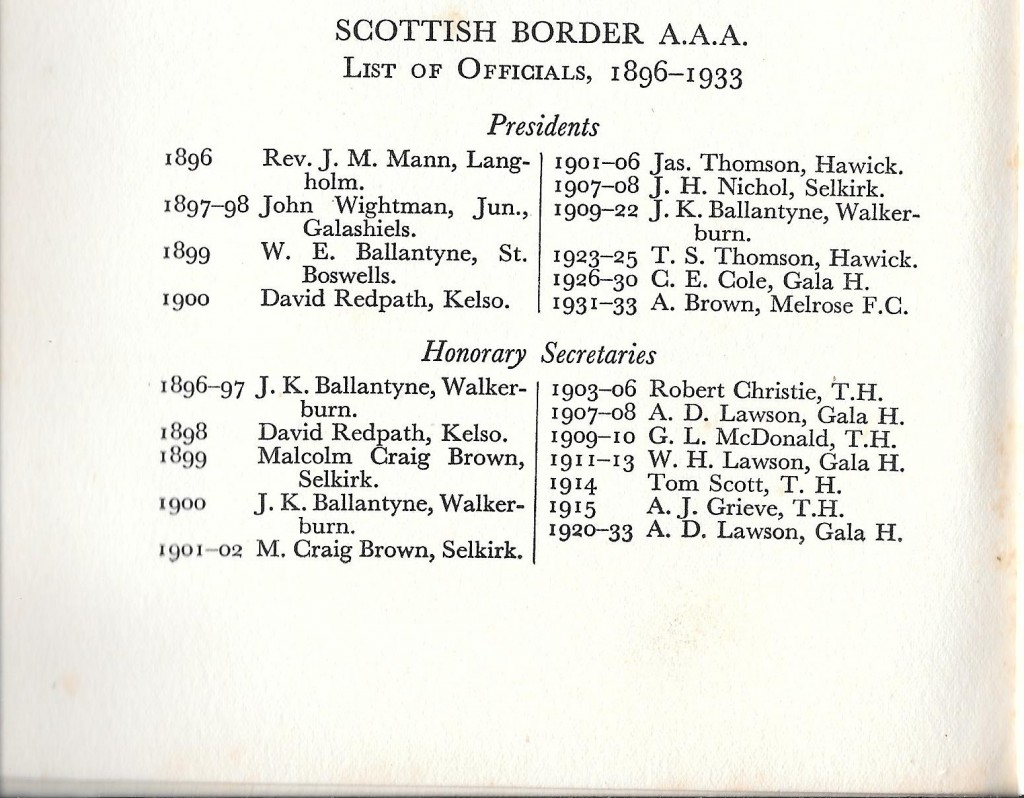

The Rev JM Mann, Langholm, was elected first President but he never, we think acted in that capacity, and John Wightman, Jnr, occupied the chair at the earlier meetings. JK Ballantyne was the first Secretary and David Redpath, Kelso, the Treasurer.

The title first proposed for the new venture was the Border Amateur Athletic Association, but it was pointed out that there were two sides to the Borders and over one f them we had no jurisdiction, so the word Scottish was added. The Committee included James Thomson (Hawick), WE Ballantyne (St Boswells), M Craig-Brown (Selkirk), and others representative of the large stretch of country under its government.

The territory first included the counties of Berwick, Roxburgh, Peebles, Selkirk, Dumfries, Kirkcudbright, and Wigton, but in the following year, the latter two, and part of Dumfries-shire, were handed back to the parent body to administer, as their geographical position and lack of good railway connections made it difficult to control them from St Boswells, the first headquarters of the Association.

Prior to the days of motor-cars, St Boswells, being an important railway junction, was the usual meeting place for anything of general interest in the Borders.

In those early days, the workers were few, but the made up in enthusiasm and hard work for their lack of numbers. Some of them are no longer with us, but were they living they would surely feel that their pioneer efforts had not been in vain.

From the beginning, the Melrose Football Club has always proved a good friend to the Association, and it was at their annual football sports in 1896 that the first race, a 440 yards handicap, was run under the auspices of the new body.

The Association itself held two meetings in the first year of its existence, one at Melrose in May and the other at Hawick in the autumn. Both these were highly successful from a sporting point of view, and did ab great deal to encourage amateur athletics. Since then, so well has the work been taken up by the affiliated clubs that it has not been necessary for the Association to hold sports of its own except the Championship Meetings, which have been instituted in the last few years.

The first sports at Melrose were a bit of a blow from a financial standpoint. In pre-motor days the railway was the only means of transport in a widely scattered district, and as the sports were intended to cater for the Borders as a whole, special trains had to be arranged and the necessary guarantees given. AR Downer had promised to run , and with his then immense drawing power, give the new Association a good send-off. Unfortunately, the English Northern Counties AAA stepped in and issued an ultimatum that if he did not run at their championships on the same day, he would probably be suspended.

Downer had been well billed all over the Borders, and the Secretary felt that in justice to the public he had to make the fact known that the great runner would not appear. In consequence the attendance was only about one-third of what it might have been. On several of the trains the guarantee had to be paid up. Those who did attend however had no cause to be dissatisfied with the sport.

The meeting at Hawick,fortunately, paid its way well, and thanks to some of the early patrons, amongst whom were Sir Richard Waldie-Griffith, the late Earl of Dudley, Lord Glenconner, Major Thorburn of Scottish rifle fame and Mr S Strang Steel of Philiphaugh, the Association was soon out of the financial shoals.

To turn from patrons to the work of the clubs, the Association should be grateful to the Hawick Football Club, who, as well as Melrose, have always included a foot-race in their football sports programme. But the two pillars of the Association have been the Teviotdale Harriers and the Gala Harriers. The healthy rivalry that has always existed between the two Border burghs has been carried into the realm of athletics, and, as rivalry is the essence of sport, so athletics in the Borders have profited by it. Other clubs, too, have arisen, some of which have not survived, bt even so their efforts still bear fruit, and although the list of affiliated clubs is not long, no large district is without one, and all are in a healthy condition. The Borders athlete is well catered for during the season.

But the greatest feather in the cap of the Association is perhaps the fact that two great representative organisations, the Hawick Common Riding Committee and the Galashiels Braw Lads Council, at their annual festivals hold important meetings under their rules. Indeed so successful have these meetings been in interesting the public that in Hawick, for this year at least, the Committee re holding a Junior Amateur Meting instead of catering for the professionals as they have hitherto impartially done on one of the two days of their holiday. Mention of junior sports reminds us of the good work that has been accomplished by the Education Committees of Selkirkshire and Peeblesshire in holding sports for their school children.

These meetings are most attractive, no one attending them can fail to be impressed by the keenness of both the competitors and the officials, drawn chiefly from the school staffs, the excellent quality of the sport and the splendid organisation which gets through a most formidable programme in the course of a little over three hours.

As a nursery for pure amateurism and young athletes they could not be bettered. Unfailing obedience is given to orders, and never a murmur against a decision is heard.

We have said a good deal about Hawick and Galashiels, but t would be a grave omission not to mention the fine efforts of the clubs in Duns and Kelso, indeed it can be said that amateur meetings have been held at one time or another during the past thirty seven years in every burgh in the Borders.

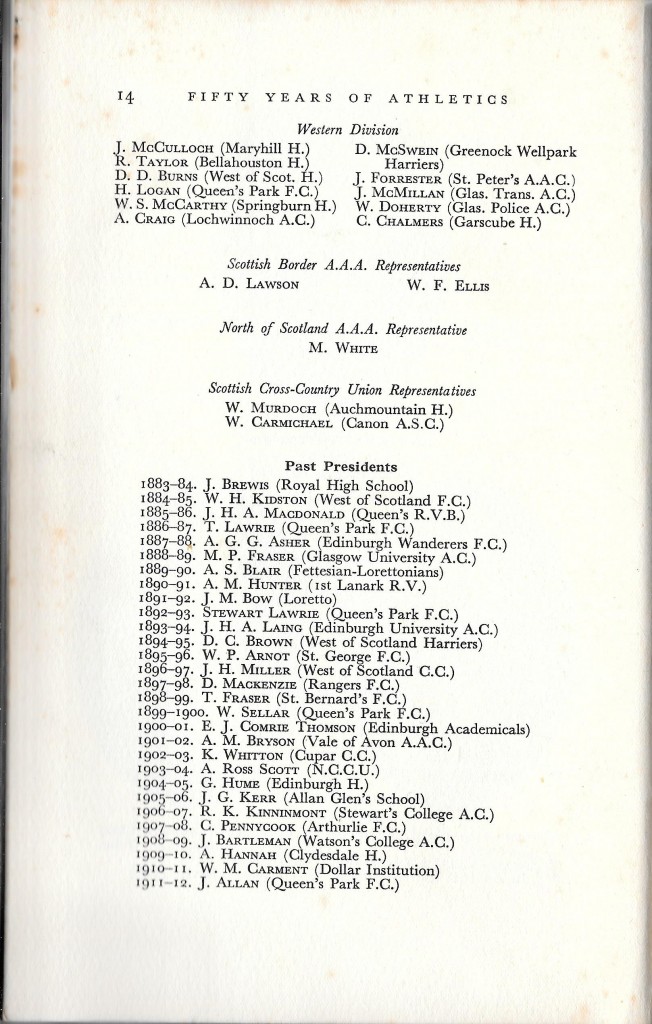

From the clubs to the athletes themselves is a very easy transition. The Borders have produced five Scottish champions:-

100 and 220 yards: JK Ballantyne 1896

220 yards: WR Sutherland 1913

880 yards: R Burton 1908, 1909, 1910

100 yards: Ian Sutherland 1927

High Jump (tie) PA Macintosh 1908

One of these, R Burton, as a record holder. All have represented their country as well as W Pollock, who ran against Ireland in 1896.

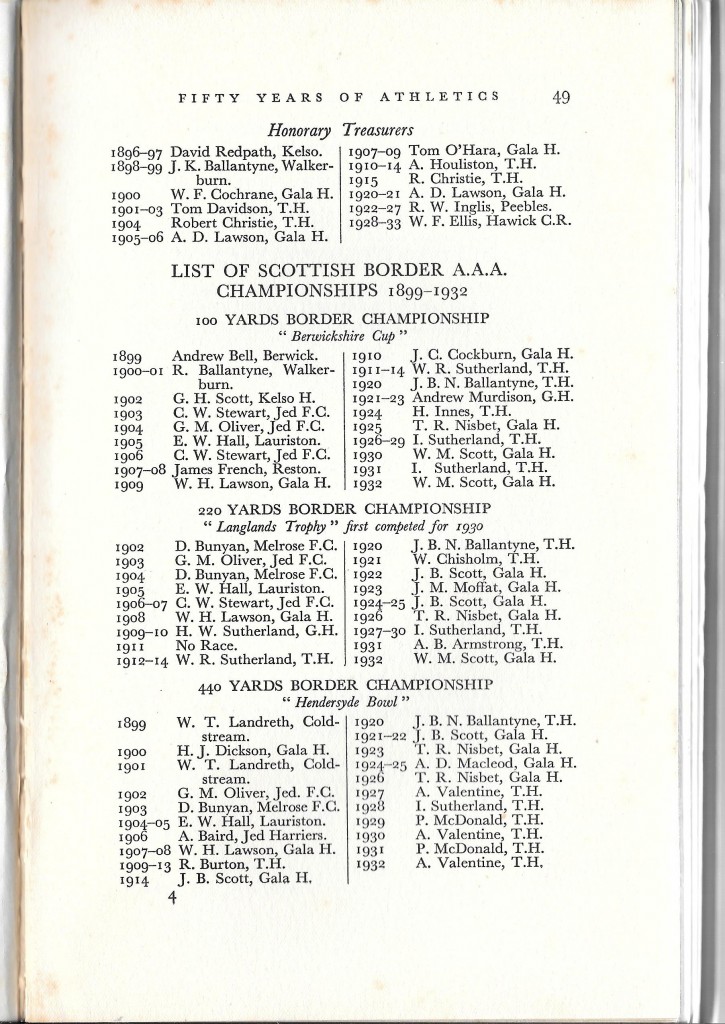

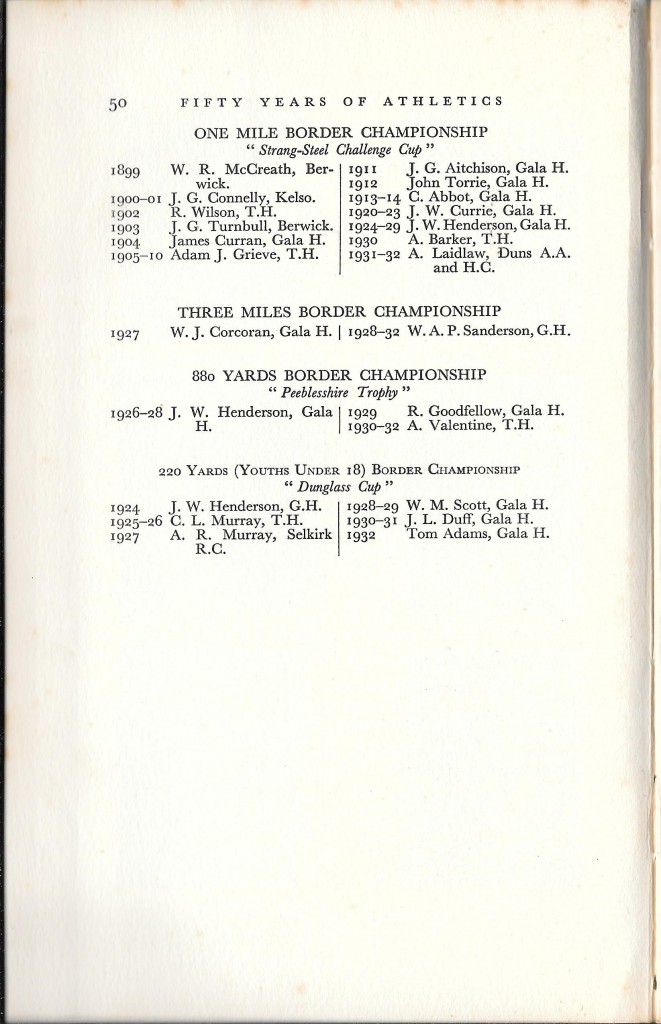

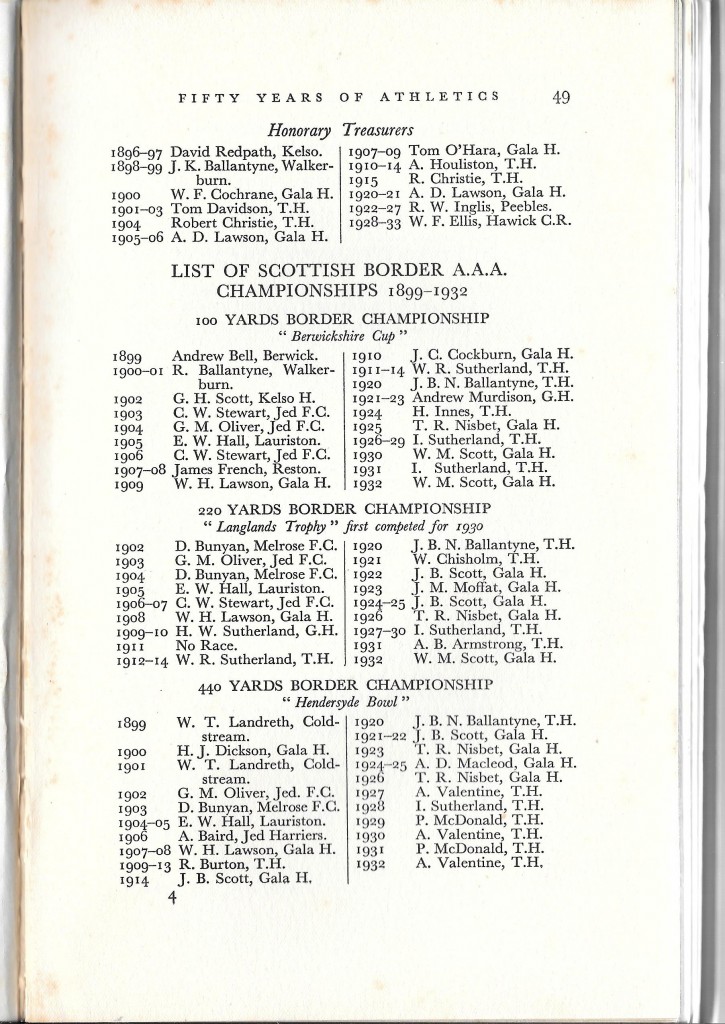

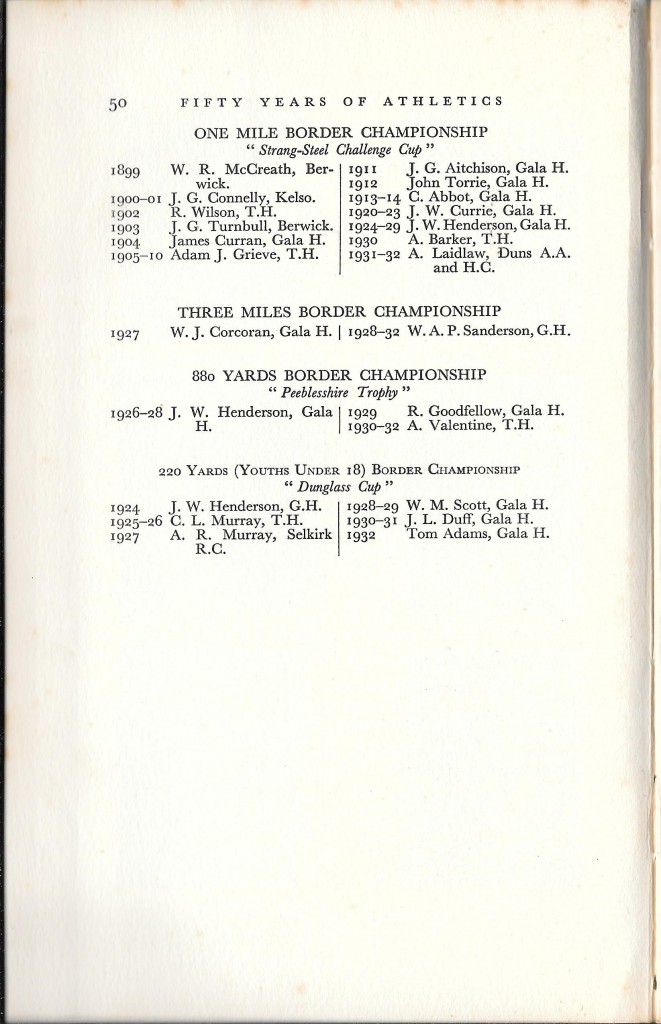

Early in its career the Association instituted Championships of its own. These were for many years farmed out to the sports holding clubs, but latterly a successful championship meeting has been run annually, and the list of winners, which we append, includes the names of most of the athletes of class that the Borders have produced.

The War took its inevitable toll, notably WH Lawson and WR Sutherland, whose pleasing personalities will always be remembered by their friends – and they were many – in two great branches of sport.

Of the officials past and present, it is perhaps sufficient to say that most of them have been unsparing in their efforts for the cause, and none perhaps has put in more spade work than the present secretary, AD Lawson, who, together with JK Ballantyne, has had the honour of presiding over the councils of the SAAA.

Amongst the donors of the Trophies that go with the various championships are Sir Richard Waldie-Griffith (Hendersyde Bowl), W Strang Steel, JR Scott (Langlands Trophy), Lord Dunglas, and the patrons of Berwickshire and Peeblesshire,

Amateurism in the Borders is of healthy growth; it has always been kept clean, and there is every prospect that it will endure.